Fear of death is a completely natural thing. After all, the thought of us ceasing to exist is quite alarming. Most people take this calmly, because this is the nature of things, and life and death are two sides of the same coin in the eternal quest of the universe for balance.

For some, the fear is further complicated by taphophobia – the fear of being buried alive. Such famous people as Alfred Nobel and Abraham Lincoln, Nikolai Gogol and Marina Tsvetaeva, Arthur Schopenhauer and Wilkie Collins suffered from it.

Not so long ago, premature burial was quite possible. In the 18th and 19th centuries, cholera victims often fell into a coma and were presumed dead. They were then quickly buried to avoid further spread of infection. In other cases, doctors mistakenly believed patients to be dead, especially in cases of catalepsy.

Such disturbing cases even inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write his book Premature Burial in 1850. In it, he describes several cases of funerals of living people, and then begins the story of his own fictitious burial.

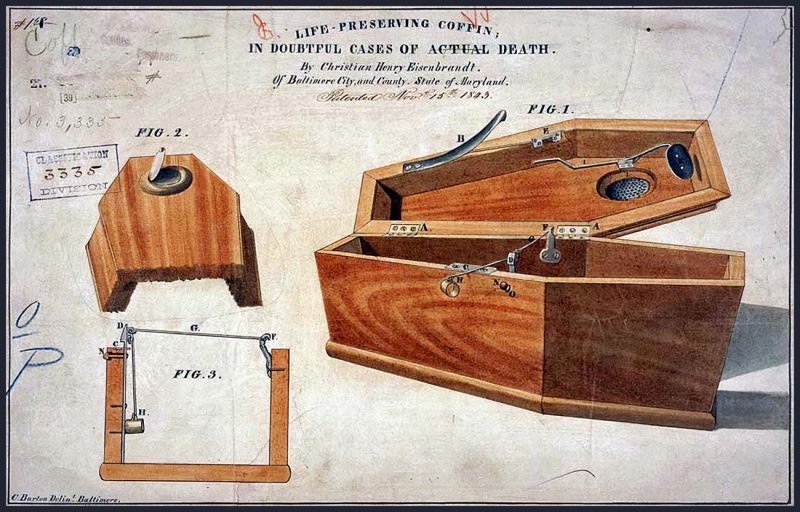

This life-and-death problem has given rise to a new industry: safety coffins.

Beginning in the late 1700s, innovative coffin makers began to develop ways for the supposed dead person to signal the living from their coffin, such as adding a bell to the grave that could be rung from below.

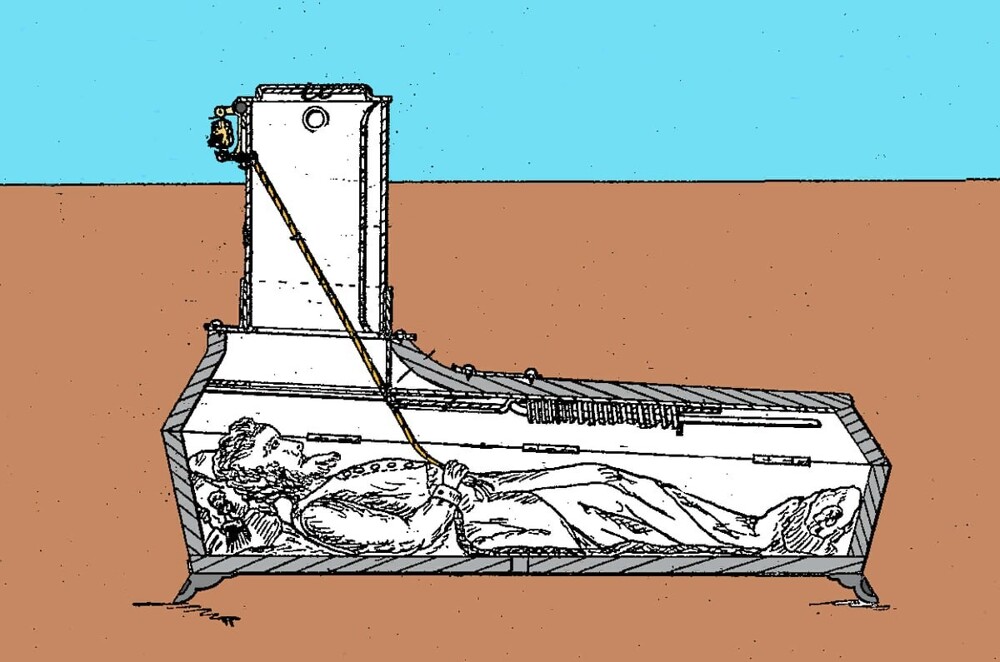

In August 1868, German inventor Franz Wester of Newark, New Jersey, took such security measures to a whole new level. He received a patent for a unique coffin that allowed someone who was not yet completely dead or mistakenly recognized as such to get out of the grave if he was able, or to signal for help if he was not. You could even store food in it - if you didn't die, you wouldn't starve - great service.

"Improved Coffin" designed by Franz Wester

An article from The Public Ledger dated October 16, 1868 describes this device:

This invention consists of a coffin similar to those now in use, except that it is a little higher to allow free movement of the body; the top cover is movable from head to chest, and in case of burial remains open, with a spring for closing. Under the head there is a container for cooling and restorative agents.

The most important part of the invention is a box about two feet square, much like a chimney, with decorative tombstones on top. The box is long enough to extend from the head to about one foot above the ground. The lid is latched from the inside and cannot be removed from the outside. Just under the cover is a bell, similar to those used in street railway cars, with a cord attached to it, which, when pulled, gives an alarm, and at the same time a spring throws the cover away from the "chimney."

If the person inside is strong enough, he can grab a rope suspended from the top of the chimney and, with the help of pegs nailed to the sides, climb into the outside world; otherwise, he can rest quietly, eat his lunch, drink his wine, and ring the bell for the cemetery attendant to come and help him out.

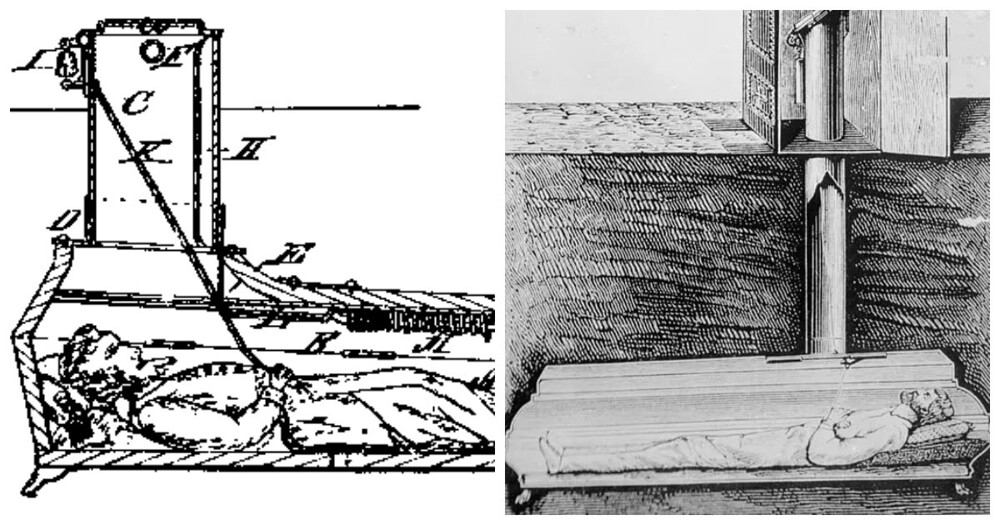

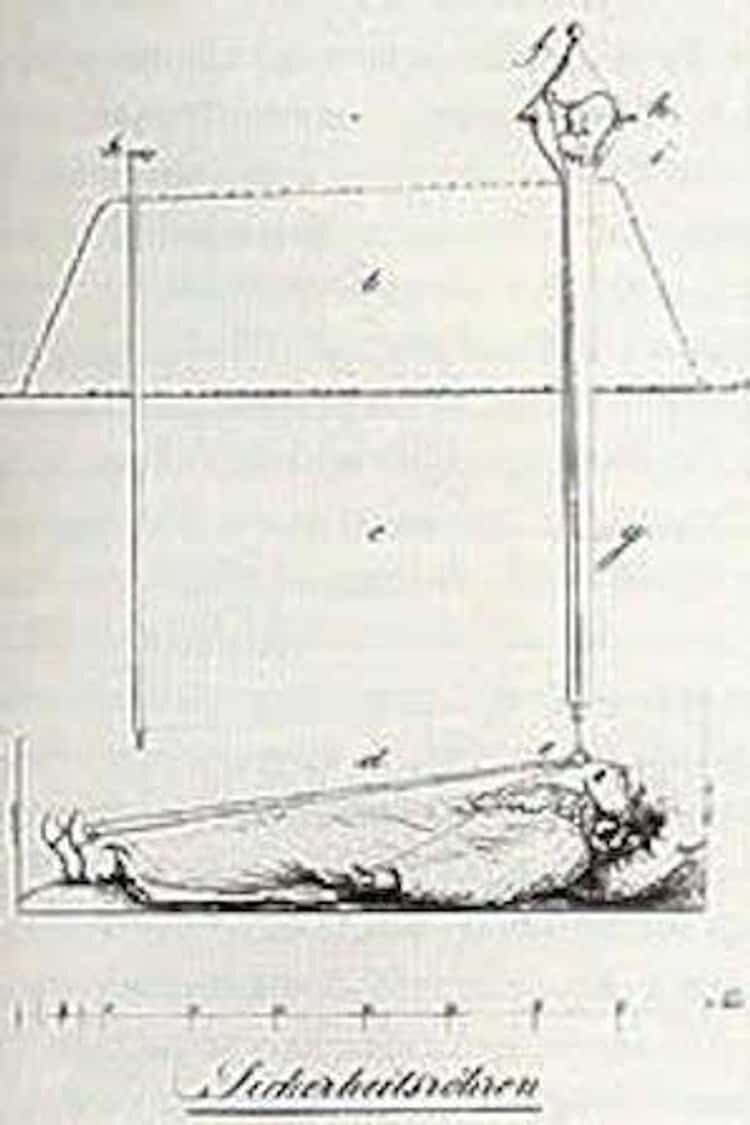

Safe coffin designed by Dr. Johan Taberger

Apparently, Wester's creation was able to turn a terrifying experience into a relaxing holiday filled with peace and quiet.

In October, Wester offered to demonstrate it. More than 600 live and healthy spectators from Newark paid 50 cents to see the life-saving device. The gravediggers prepared the hole and Vester climbed into his coffin, ready to be lowered into the ground. The “chimney” was installed in place, after which the gravediggers took shovels in their hands and buried the inventor alive.

Vester planned to stay in the grave for several hours, but the crowd became agitated and the signal was given for the showman to exit.

“A minute after this, Mr. Wester emerged unassisted from his living grave,” the article reported, “with no more appreciable exhaustion, hI eat while walking two or three blocks in the hot sun.”

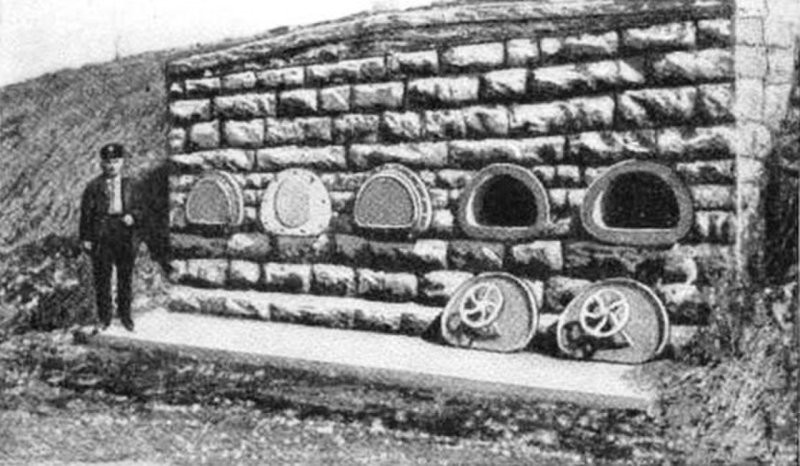

A crypt with a self-rescue system for someone buried by mistake

Wester's tomb was just one of many new structures. In Ian Bondeson's book Buried Alive: The Terrifying Story of Our Greatest Fear, he describes later patents with more advanced technology, including electrical signals that launched flags, bells, rotating lamps, a heater, and even a telephone. Regarding the latter, Bondeson told the story of a Louisiana woman, Mrs. Pennord, who was buried with a telephone connected to the cemetery caretaker's house in 1908.

Thus, an attempt to make money on one of the main human fears is quite real and no worse than any other business. With the development of modern technology, perhaps the most popular souvenir that is placed in the coffin of the deceased has become a mobile phone. Only this moment is more of a fashion statement, since the air supply in the coffin will last for a maximum of six hours. And if help does not arrive during this time, then the imaginary dead person will finally become real.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: