Who is "hook"? Forgotten, but bread in every sense, the profession of the past (13 photos)

One of the most popular articles on my channel, published recently is a publication that talks about such a profession as "konoval". I won't repeat myself unless read, be sure to do it (link below), but its success prompted me to the idea of creating a whole series of articles about forgotten today professions.

I am sure it will be interesting and informative. And today we will talk about such a profession of the past as a "hooker".

Who is this and how did he earn his living? All Just. He carried this very bread on his back. In the form of a grain. barge haulers dragged a loaded ship to the river pier, where its hooks were already unloaded. Or, I would even say, overloaded. But more on that below.

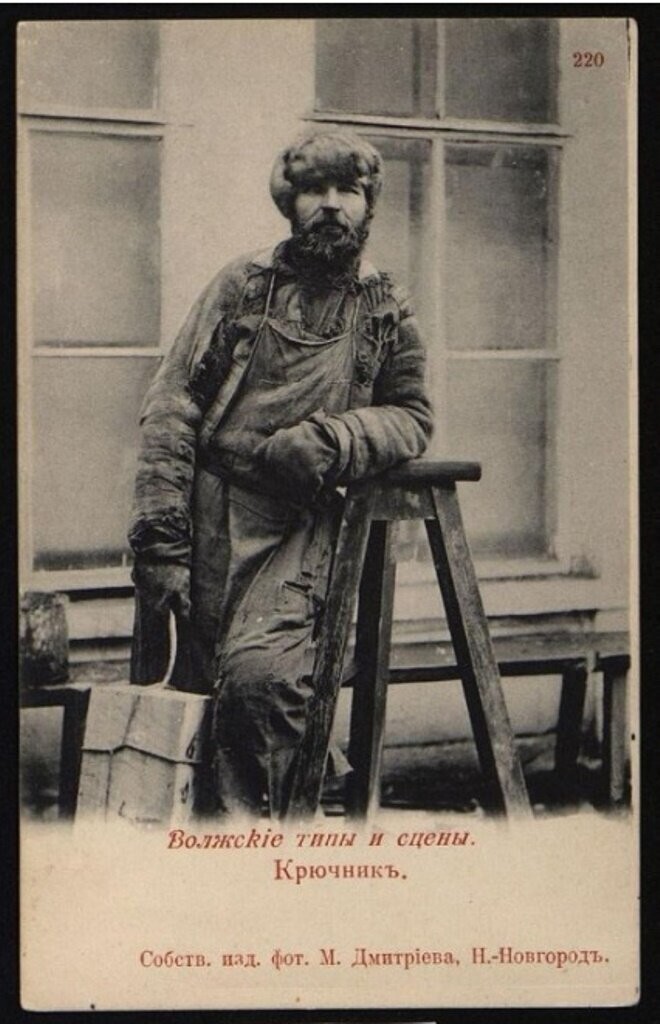

Today hookers would be called simply port loaders. But they had one nuance that distinguished them as a separate, so to speak, subspecies of loaders.

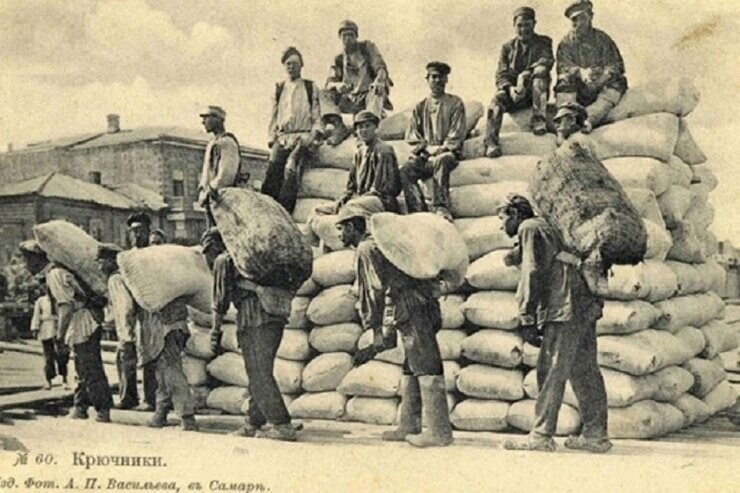

In their work, these guys used a special tool that facilitates their hard work. This is a "saddle" (aka "stool"), representing a canvas-wooden "unloading", which was worn on the back of the hooker and had a strong emphasis on which bag was placed. It can be seen in the region of the lower backs of men in the photo above, but I'll show it to you separately:

The second assistant of any self-respecting hooker was metal hook. Hence, in fact, the name of the profession. By using him a sack of grain was raised and kept on the saddle.

There were other options for the execution of hooks, but the essence, I think, understandable. Let's dive into the finer nuances of the Volga hooker profession.

It was not without reason that I emphasized that this is a craft in the mass its spread in the Volga region. In Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Saratov and other cities. But there were especially many of them in Rybinsk.

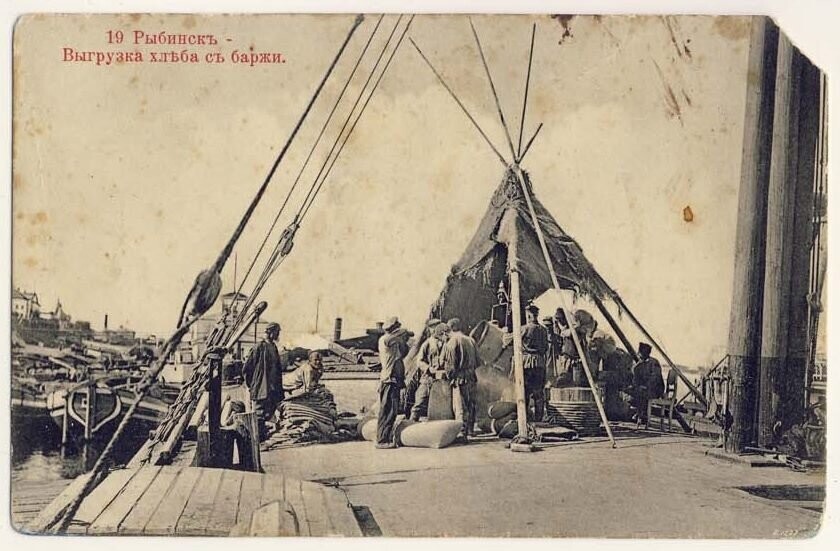

To understand why it is there, one must remember that Rybinsk It is located at the confluence of the Mother Volga and the Sheksna River. Last was part of the so-called Mariinsky water system, through which the capital, i.e. St. Petersburg, was supplied with everything necessary. Thus, Rybinsk was not only the largest grain exchange in Russia, but also a powerful transshipment point. From large ships, all cargo had to be reloaded onto flat-bottomed barges, since after Rybinsk the Volga became very shallow.

At the same time, a small town was called the "capital of barge haulers" for a reason. In the book "Description of the city of Rybinsk" by M. Gomilevsky in 1837 we read:

“All marinas, small and large, in Rybinsk counts nine. Beautiful views open up from the banks of the Volga - flaunts richest port. From May to August, the majestic Volga is covered thousands of ships, whose tall masts make a lovely view of the thick groves"

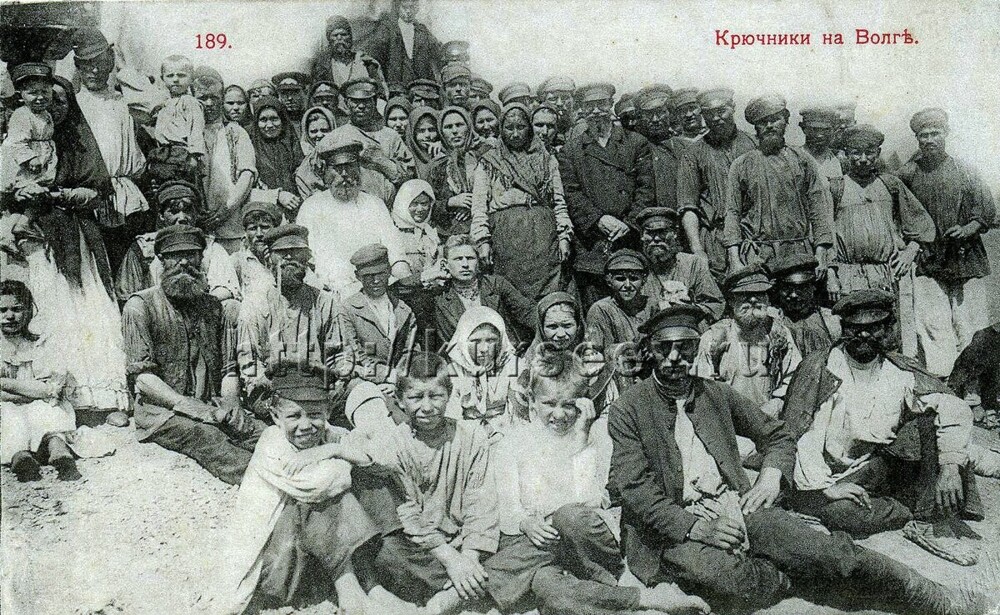

We learn from the same author that during the navigation season in Rybinsk gathered to earn up to 130 thousand people, while the population of The city at that time numbered about 7 thousand.

The hookers were most often hired by peasants closest to Rybinsk counties, as well as retired soldiers and poor townspeople. Part barge haulers, who had reached their load, were also hired as hookers. For example, such an increase in the "career ladder" happened to the future writer Vladimir Gilyarovsky. In his youth, he, calling himself Alyoshka Ivanov, decided to try his hand at barge haulers, and later managed to win authority and take root in one of the artels of hookers.

Such artels consisted of 12-16 people. Depending on the type of operation performed, they were divided into exhibitors, hunchbacks and batyrs. The first put the coolies with grain on the deck, the second - heaped the load on their shoulders and dragged to another ship. There is a batyr, that is, a senior, commanded where, what and how to store. For a working day, every hunchback endured an average of 200 to 400 sacks. The average weight of a sack with grain, as reportedly was 9 pounds, that is, almost 150 kg.

Why exactly 9 pounds andwhy merchants forced hookers carry such burdens? They saved on the cost of packaging: the sack itself, then there is a bag, the purchase cost the merchant 30-50 kopecks, which is not a little, given that the price of rye was 3.5-4 rubles for the same 9 pounds.

Met on the Volga piers and especially gifted by nature hookers. These were called ambals or carts. These were the strong men about whom legends were made. The aforementioned Gilyarovsky ended up in the artel. In My Travels, he wrote:

“... Three days later, I was already famously coping with nine pounds sacks of flour and, although at first my back hurt, and especially the calves of my legs, a week later I got a promotion: I was offered to sheathe a vest with gold galloon. I joined the artel and, having worked for a month, became blacker than an Arab, stuffed iron muscles and did not know tired ... "

Silver and gold lace had the right to wear the strongest and hardy hookers. Unfortunately, all these "records" later had unpleasant health consequences, but more on that later.

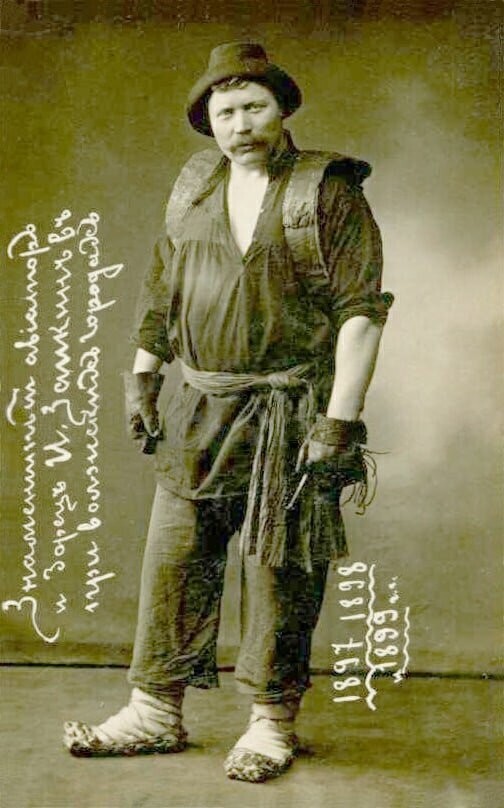

In the photo above, the once famous circus wrestler Ivan Zaikin dressed as a hooker in 1897-99 He was originally from the Volga region and in For 15 years, his father gave him to work as a hooker on the pier. He later went to "athletes" and performed in the troupe of Ivan Poddubny.

I can’t help but give another quote from Gilyarovsky about his heroic colleague named Repka:

“... And he himself receives as much as the batyr, because that works on a par with them, despite its almost seventy years, still jokes: either he will bring two sacks, then he will put a hefty one on a sack the clerk and, to the marvel of everyone, will easily run away with him along the unsteady gangway ... "

Well, since we are talking about wages, let's continue this topic. Several sources report that for their work hardy hookers received quite well - up to 5 rubles a day. For In comparison, a skilled worker then received 2 rubles a day. However, most of them spent all the money they earned on booze.

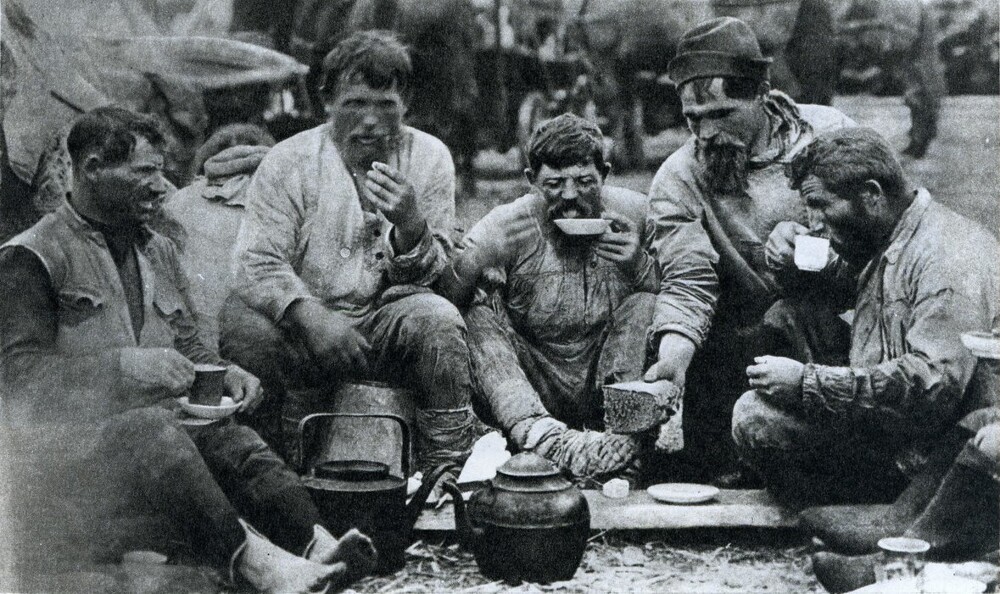

“The hookers went down to the water, knelt or lay face down on the gangway or on rafts and, scooping up handfuls of water, washed wet, inflamed faces and hands. Right there on the shore, off to the side where there was still some grass left, they settled down for dinner: they put it in a circle a dozen of the most ripe watermelons, black bread and twenty rams. Gavryushka Bullet was already running with a half-bucket bottle to the tavern and singing soldier's signal for dinner ... ".

(c) Kuprin A.I., "Pit"

Let's not forget about seasonality. In winter, work for them there were no obvious reasons. Some prudently returned to their villages, while others went to the porch, and some robbed. In a note to Supreme Administrative Commission of 1880, Major General E.V. Bogdanovich reports the following about the hookers who wintered in Rybinsk:

Passportless are known in the city under the informal the name of "Zimogor", i.e. people for whom winter is grief. Once upon a time a young worker, honest, healthy, with a legal passport and strong hands, he came to Rybinsk to work on ships. He was accepted, given a job, they gave money, but the money gradually passed into drinking houses, and the worker winter was left without money, and without work, and even with an expired passport. Hungry for winter, let down some clothes - nothing, he thinks, he will come summer - I’ll get better, pay the arrears, change my passport, then go home ... But summer passed like last year, only one thing has changed: one "Zimogor" has become more ...

It is obvious that such exhausting work is catastrophically affected the health of these poor people. Particularly on the spine. Not I exclude that many of the hookers partly abused alcohol. So to speak, as an anesthetic. Besides, in At the end of the 19th century, there were many cholera diseases on the Volga. Same Gilyarovsky wrote that the elderly and wise Repka punished his artel in no way in no case do not drink raw water, but only hot tea and ... vodka.

Well, the last thing to say about the Volga hookers. It turns out that Chaliapin's "Dubinushka" is not a song of barge haulers, namely Kryuchnikov. In 1890, seventeen-year-old and still unknown Fedor Chaliapin was forced to join the artel due to financial problems Samara hookers, where he worked for about a week. This was enough to forever remember the song that will become one of the most famous in his repertoire.