To Each Their Own: Buchenwald - the most terrifying concentration camp (13 photos)

Buchenwald is the most recognizable symbol of Nazi cruelty, the system of repression and the total destruction of the human personality.

The concentration camp began its "operations" even before the start of World War II—in July 1937. It was built near Weimar, in Thuringia, in a picturesque beech forest.

The location was chosen deliberately: it was remote from major population centers, allowing the events to be concealed behind barbed wire. The first prisoners arrived from other camps—Sachsenhausen, Lichtenburg, and Sachsenburg. Among them were political dissidents, members of sects, criminals, and men of the wrong orientation. But even then, it was clear that the camp was created as an instrument of repression against anyone who did not conform to the ideological norms of Nazism.

The first commandant was Karl Koch, a man of monstrous character, known for his cruelty. It was he who established a brutal regime, which his successors only strengthened. Later, after his assassination (on orders from Himmler himself), control passed to Hermann Pister, who continued the policy of terror.

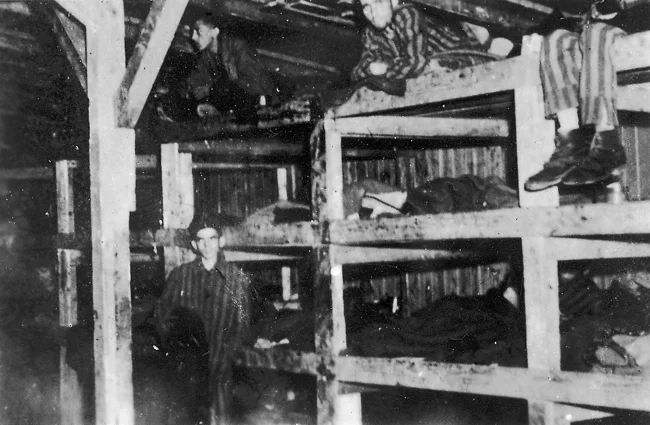

Liberated Buchenwald prisoners, April 16, 1945

Over the years, approximately 250,000 people passed through Buchenwald. According to various sources, approximately 56,000 of them died. They were people of various nationalities, faiths, and social statuses. But they had one thing in common: they fell outside the "Aryan" standard or simply opposed the regime.

Conditions of detention and labor exploitation

The camp had a strict system of categorizing prisoners—each group had its own distinctive markings and faced a particular degree of discrimination. The situation was especially difficult for Jews. They were under constant threat of death or being sent to Buchenwald subcamps, such as Dora-Mittelbau, where conditions were even worse.

Monument to the Victims of Buchenwald

Prisoners were used for hard labor for German industry. Each day began with endless formations, after which they were sent to work, often in dangerous conditions. Companies like Siemens, Daimler-Benz, and I.G. Farbenindustrie received free labor, which was exhausted and died from hunger, disease, and abuse.

Buchenwald Train Station

Labor was not only a means of exploitation, but also a method of extermination. People worked to the point of exhaustion, food was minimal, and sanitary conditions were appalling. The daily ration could consist of just a few slices of bread and bad soup. Many died on the job or in the barracks, where their bodies remained until morning.

Medical Experiments: Science and Death

One of the most horrific aspects of life in Buchenwald was the medical experiments. Prisoners were subjected to experiments without anesthesia, without consent, and without any purpose other than to brutally test the limits of human endurance. People were infected with dangerous diseases. The goal was to test vaccines, but the price was hundreds and thousands of painful deaths.

The sign on the main gate reads, "To each his own."

Particularly well-known are the studies of Dr. Karl Vernet, who conducted hormonal experiments on men. Under the guise of treatment, he implanted capsules containing male hormones into their groins, supposedly to "cure" them of sexual orientation. These operations were performed without anesthesia, and many of the subjects died from complications. Fortunately, documents from these experiments survived and were later used in court cases.

Soviet Prisoners of War and Other Victims

With the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War, Soviet prisoners of war began to be sent to Buchenwald. They were held separately and subjected to particular cruelty. Many were simply shot. According to some sources, approximately 8,000 Soviet soldiers died in the camp or in the nearby SS stables, which served as a site of mass executions.

Buchenwald Crematorium

But Soviet citizens weren't the only victims. The camp included Poles, French, Czechs, Austrians, Belgians, Italians—practically every European country was represented. It was a veritable international hell, where survival was a daily matter.

Underground and Resistance

However, even in such hell, resistance arose. In 1943, an International Camp Committee was created within the camp. Its members—representatives of various countries and nationalities—organized assistance for one another, collected information, and passed it on beyond the camp. This committee later created a Military Organization, which prepared for an uprising.

Buchenwald Crematorium Ovens

The Military Organization managed to occupy key positions in the camp, collect weapons, make homemade grenades, and even hide a homemade machine gun. Combat groups were at work: Soviet, French, Polish, Yugoslav, and Italian. All of them worked together, despite differences in language and culture.

Uprising and Liberation

The uprising was planned for April 1, 1945, but was postponed several times. Finally, the decisive moment arrived on April 11, when American troops were already approaching Weimar.

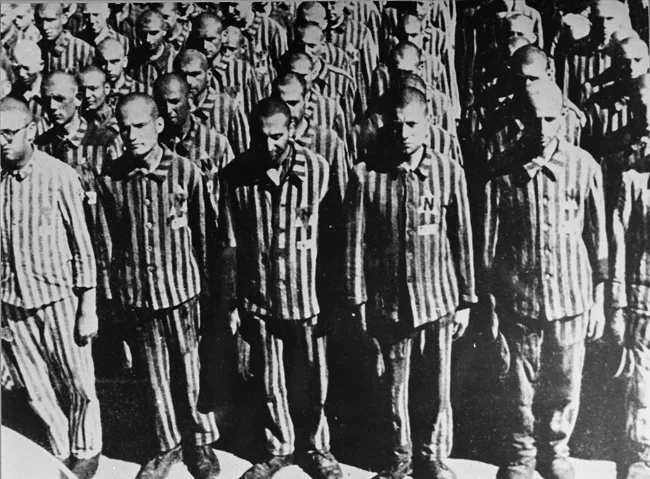

Newly arrived Polish prisoners undress before being washed and shaved.

A few days earlier, a group of prisoners, including Polish engineer Gvidon Damazin and Soviet POW Konstantin Leonov, managed to establish contact with American troops via a homemade radio transmitter. The last radiogram read: "To the Allies. General Patton's Army. This is Buchenwald concentration camp. SOS. We request assistance. They want to evacuate us. The SS wants to exterminate us."

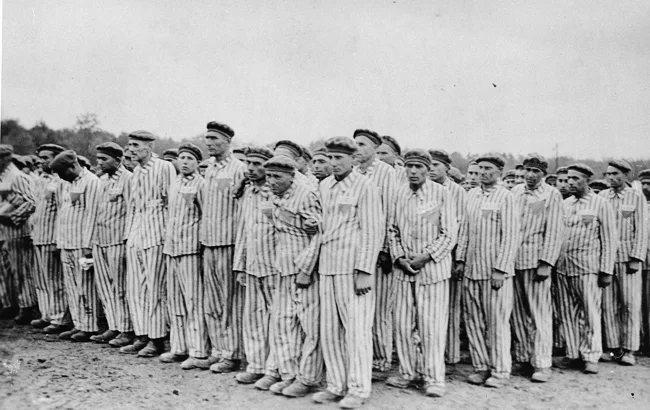

Prisoners stand during roll call.

The reply came quickly: "Buchenwald concentration camp. Hold on. We are rushing to your aid." And indeed, salvation had arrived. On April 11, the uprising began. The prisoners stormed the guard towers, seized the commandant's office, and organized a defense. Two days later, American troops entered the camp. This event became a historical turning point, and that's why April 11 is now celebrated as International Day of the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camp Prisoners.

The Camp After the War

However, Buchenwald's history did not end there. After the war, the camp grounds were handed over to the Soviet Union, and NKVD Special Camp No. 2 was established there. It was now used to house those considered Nazi criminals. Over the course of its existence, more than 7,000 people died there.

Dutch Jews during roll call after the prisoner transport from Buchenwald to the camp in May 1941.

After the war, the trial of the Buchenwald staff began. An American military tribunal sentenced 22 defendants to death, although some of their sentences were later commuted to prison terms. However, many were soon released and continued to live without fully answering for their crimes. Some, like Erich Wagner, committed suicide before being sentenced.

On April 26, 1942, twenty Polish prisoners were hanged in retaliation for the murder of a German guard.

In subsequent years, individual courts in various countries attempted to achieve justice. For example, physician Werner Kirchert was sentenced to four and a half years, and one of the most brutal guards, Martin Sommer, was sentenced to life imprisonment. However, he was released in 1971.

Memory and Cultural Impact

The memory of Buchenwald never fades. A memorial complex was established there, unveiled in 1958. It includes surviving elements of the camp: a crematorium, the remains of barracks, watchtowers, barbed wire, and the famous sign on the gate: "Jedem das Seine"—"To each his own." This phrase is especially chilling when you consider that everyone was given what the regime intended for them.

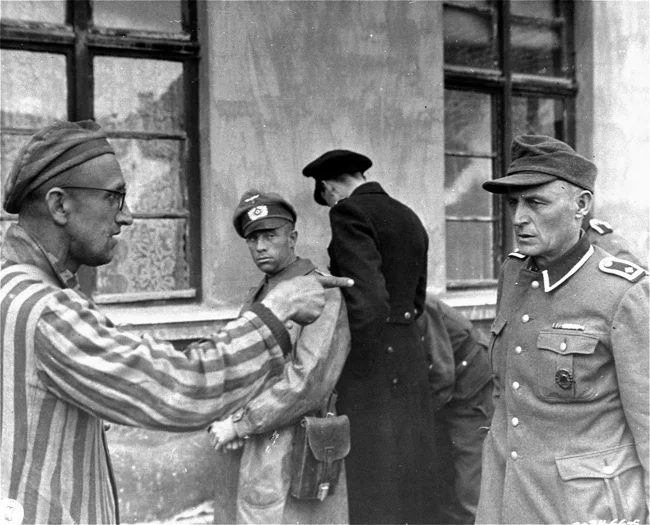

A Buchenwald concentration camp prisoner with an SS guard after entering the US Army camp, 1945.

Furthermore, the events of Buchenwald have inspired literary works. For example, Erich Maria Remarque's novel "The Spark of Life" is based on real events. Also well-known are Georgy Sviridov's novel "Ring Behind Barbed Wire" and Bruno Apitz's book "Naked Among Wolves," which tells the story of the rescue of a Jewish child in a camp.

Numbers and Statistics: The Scale of the Tragedy

According to official data, approximately 250,000 people passed through Buchenwald. Of these, approximately 56,000 died. These are numbers, but behind them lie real lives. These are mothers, children, fathers, friends. These are entire families destroyed by the system.

Statistics also show how the prison population changed over the years. While in 1938 the camp held approximately 11,000 people, by 1945 the number had reached almost 80,000. This demonstrates how Nazi Germany's repressive machine intensified as its defeat approached.

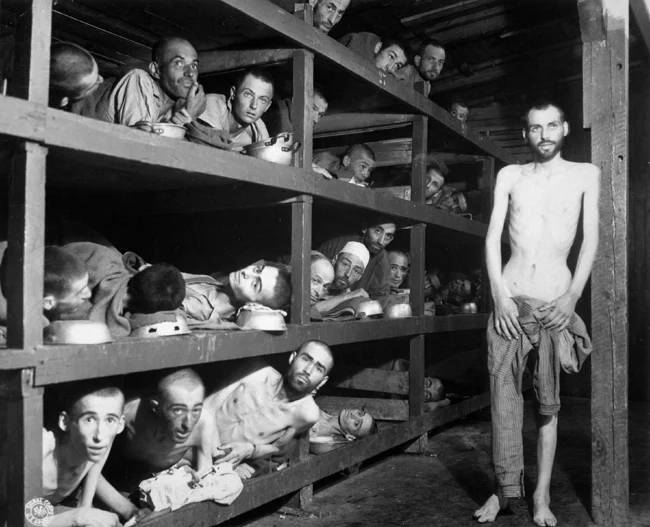

Barracks interior, photographed by Jules Rouart [fr] on April 16, 1945

You may ask: why remember all this? The answer is simple: because forgetting is repetition. Buchenwald is not just a page of history; it is a lesson that should prevent us from repeating the mistakes of the past.