A giant lake that disappeared: where did this aquatic wonder the size of the Caspian Sea go? (6 photos)

Millions of years ago, during the Pleistocene, a vast expanse of water—a megalake, comparable in area to the Caspian Sea—stretched across the site of modern-day Chad. It would shrink and then expand to the horizon, transforming the plains into a boundless body of water.

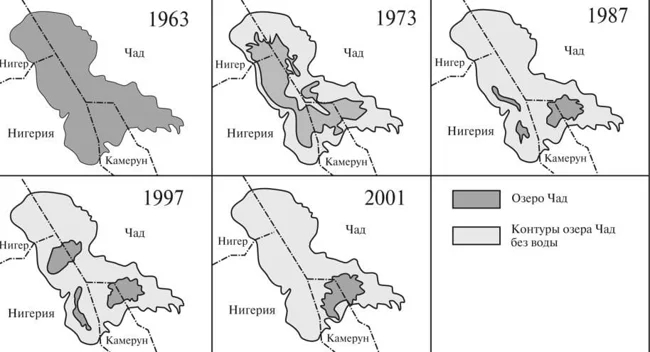

Back in the 1960s, quite recently by historical standards, the lake covered approximately 25,000 square kilometers. It was the heart of Central Africa: it provided food for fishing villages, watered livestock, sheltered flamingos and hippos, and during the rains, transformed its banks into a network of lagoons and channels.

Tipping Point

The current tragedy bears little resemblance to natural climate cycles. Since the early 1970s, rainfall has become increasingly rare, heat has risen faster than global averages, and the rivers that feed it—the Hadejia, Komadougou-Yobe, and Logone—have shrunk to the point of parched vessels. Only memories remain of its former grandeur: the water surface has shrunk to 1,350 square kilometers.

Photos from the last century and satellite images from the 21st century reveal a dramatic difference. Chad's history resembles the tragic fate of the Aral Sea: not a sudden collapse, but a slow, painful disappearance.

How the Lake Died

In the 1960s, the waters receded barely noticeably. But by the 1970s, the northern part had completely dried up, leaving behind the salt marshes of Bodele. The dry bed has become the source of gigantic sandstorms: up to 700,000 tons of dust are blown into the Atlantic annually, as if the lake were scattering its own dust.

By the 1980s, it had divided into two separate basins connected by narrow channels. The drought of 1984 nearly ended its history: the water level dropped by 4 meters, and salinity tripled, killing most freshwater fish.

In the 1990s, the situation worsened. The Komadougou-Yobe River no longer reached Chad: its waters were diverted to irrigate cotton and rice plantations in Nigeria. In NASA images, the lake began to resemble a dirty spot. By 2001, its area had shrunk to 1,800 square kilometers.

Ecological Domino Effect

Each new decline in the water level caused a cascade of problems. The shallow waters warmed faster, increasing evaporation. Fish populations died out, including the legendary Nile perch. Dense mats of algae—the "green devil"—grew in the channels, hindering boats and clogging wells.

Meanwhile, the region's population has grown tenfold since the mid-20th century, to 50 million. People flocked to the shrinking shores, forming slums and draining the last resources. Fishing villages that once stood on the water's edge found themselves tens of kilometers away in the 2010s.

Last Hopes

Heavy rains in 2020 briefly restored some of the water, increasing the area to 5,000 square kilometers. But 80% of this moisture was lost to sand: the soil, destroyed by droughts, is no longer able to retain moisture. By 2023, the average depth of Chad Lake was no more than one and a half meters—an adult can cross it on foot.

In 1994, four countries in the region created the Lake Rescue Commission. The most ambitious project, Transaqua, envisioned digging a 2,400-kilometer canal from the Ubangi River to Congo to restore Chad to at least some of its former power. But political disputes, colossal costs, and fears for Congo's resources stymied the idea.

Meanwhile, local residents are seeking their own solutions. In Nigeria, women are planting "green walls" of acacia trees against encroaching dunes. Cameroonian farmers are introducing drip irrigation. Fishermen are switching to salt production, moving ever further from the shore.

Lake Chad as a Mirror of Humanity

The history of Chad is not simply the drying up of a lake. This is the death of an entire ecosystem, where every new wound—climatic, demographic, or political—becomes part of the overall collapse. The lake doesn't die instantly, but from a multitude of small blows, almost all of which are inflicted by humans.