The inconspicuous Aspidistra, which became the main plant of the era (14 photos)

Houseplants have adorned people's homes for thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans kept greenery in their spacious homes.

The Romans were especially fond of brightly colored flowers and often decorated their homes with large, lush roses and violets.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, ornamental gardening in Europe virtually disappeared, giving way to a utilitarian approach. People grew mainly herbs, vegetables, and fruits—things they could eat. Houseplants only came back into fashion during the Renaissance, when wealthy and noble citizens began to see them as a symbol of social status.

Exotic species such as nasturtiums and sunflowers were brought from the New World to Europe and presented as gifts to monarchs. These capricious flowers required special conditions similar to their native climate, which could only be created in greenhouses and winter gardens.

Those who couldn't afford a conservatory or a staff to care for their plants often rented plants from nurseries during visits. Others sent their potted plants back to nurseries for the winter, where gardeners tended them for a fee.

The most challenging time for houseplants was the 1800s, when gas lighting was introduced to Victorian homes. Gas lamps emitted toxic smoke that caused headaches and nausea, blackened ceilings, faded curtains, rusted metal, and left a layer of soot on every surface.

Aspidistra

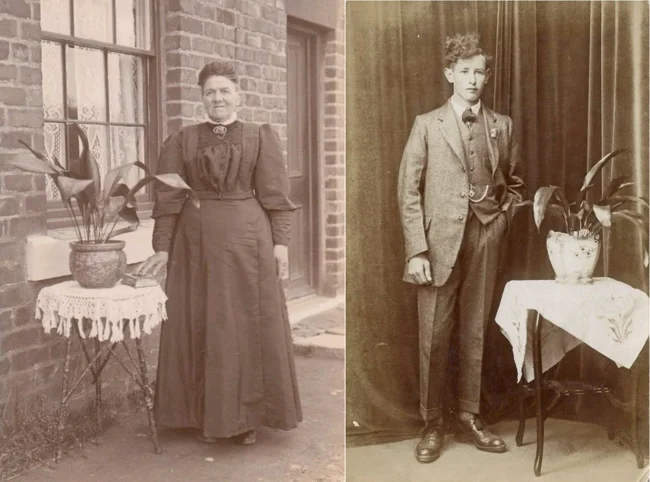

Flowers and most plants withered. Only two exceptionally hardy plants managed to survive in this gloomy environment: the Howea forsteriana, or kentia, and the Aspidistra. These plants, and especially the Aspidistra, became indispensable attributes of every drawing room, boudoir, hall, and fashionable ballroom of the Victorian era.

Aspidistra is an amazing plant. Native to Japan and Taiwan, this slow-growing evergreen perennial with glossy dark green leaves was brought to Europe in the 1820s and quickly earned the nickname "cast iron plant" due to its phenomenal resilience, even when handled with care.

It can survive extreme temperature fluctuations, withstand drought, most pests, and even thrive in the dim light and poor air of a Victorian home with gas lamps. Aspidistra became so popular in Victorian Britain that, as the Oxford Dictionary notes, it became "a symbol of middle-class respectability."

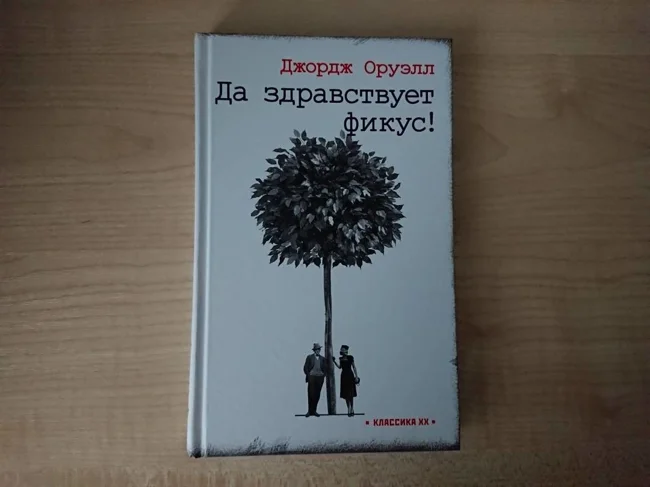

George Orwell, in his satirical novel "Long Live the Ficus!" published in 1936, used the aspidistra as a symbol of the prudishness of the Victorian middle class. The plant also featured in musical numbers, such as Gracie Fields' song "The Biggest Aspidistra in the World," which in turn inspired the British Secret Service to name its transmitter, built during World War II to disrupt enemy communications, "Aspidistra."

Howea

Another plant that gained popularity in Victorian homes was the Howea forsteriana, or kentia. This plant is native to Lord Howe Island in Australia, from where its seeds were brought and cultivated throughout Europe and the United States in the late Victorian era.

Like the aspidistra, the kentia can thrive in conditions that are harmful to other plants: low light, low humidity, poor air quality, and cold temperatures.

Queen Victoria adored these palms. She grew them in all her residences, and this connection to the royal family gave a certain prestige to those who could decorate their homes with them.

Many Edwardian hotels, such as The Ritz in London or The Plaza in New York, decorated their lobbies with howeas. They can still be found in modern hotels, casinos, and shopping malls.