Scientists have revealed the secret of "hairy" medieval books from France (3 photos)

In the dark halls of the French abbey of Clairvaux, books covered in strange skin with hairs have been gathering dust for centuries. For a long time, no one could understand whose skin protected the old texts until an international team of scientists conducted an analysis.

Founded in 1115 in the Champagne-Ardennes region, the abbey of Clairvaux became a center of knowledge for the Cistercian monks. Thousands of manuscripts were copied and stored there: theological treatises, historical chronicles, legendary bestiaries with descriptions of mythical creatures. By the 13th century, the abbey library was considered one of the largest in Europe. About 1,450 books from this collection have survived to this day. Almost half of them have their original covers.

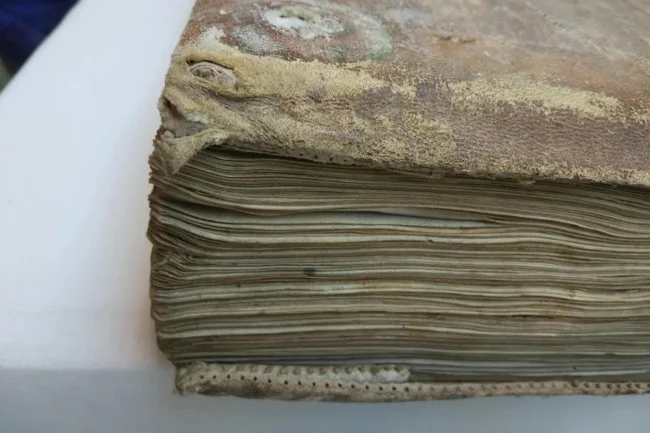

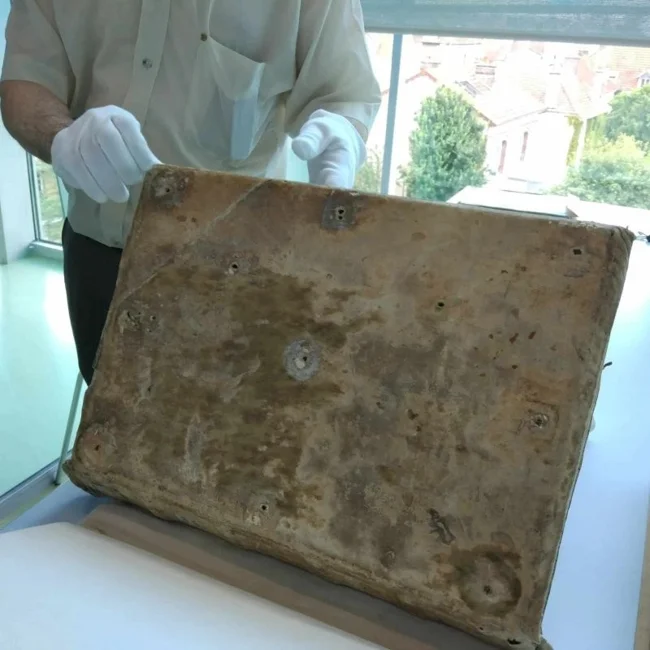

Books from that era looked different from modern ones. They were created by hand: sheets of parchment were placed between wooden boards and sewn together with strong threads. Some volumes were “wrapped” in an additional outer cover, which was covered with leather. Most often, calf, goat or sheep skins were used - they were carefully cleaned of wool so that the surface remained smooth. But Clairvaux contained dozens of manuscripts with hairy covers. They did not look like typical medieval bindings - too rough and “shaggy”.

For a long time, historians assumed that the “hairy” bindings were made from boar or deer skins. But when the researchers examined 16 of these books in detail, they were in for a surprise. An international team of scientists led by British bioarchaeologist Matthew Collins from the University of Cambridge collected microscopic samples of skin by carefully erasing the inside of the covers with an eraser.

An analysis of proteins and fragments of ancient DNA revealed that the material had nothing in common with local animals. The source of the skin turned out to be seals: samples belonged to common seals (Phoca vitulina), Greenland seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus), and one even to a bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus). Genetic analysis has shown that the animals may have come from Scandinavia, Scotland, or perhaps Iceland or Greenland.

How did the skins of sea animals end up in a monastery located far from the coast? The answer lies in the network of trade routes that connected the remote corners of the continent. Traders from Scandinavia brought furs, skins, and fat from sea animals caught in northern waters to Europe. Clairvaux Abbey stood next to a busy trade route that carried goods from port cities to the monks.

The seals themselves were valued not only for their skin, but also for their meat and fat. Their skins were often used to make waterproof clothing, such as boots or gloves. In some regions, seal skins were even used to pay church taxes. On the coasts of Ireland and Scandinavia, they were sometimes used to make book bindings. However, in Western and Central Europe, this practice was extremely rare.

The Cistercian monks, apparently, especially valued sealskins. Scientists have found "hairy" bindings not only in Clairvaux, but also in other abbeys founded by his disciples. The monks used this unusual material to bind especially important documents - for example, the life of St. Bernard, one of the key figures of the order.

Why did the monks choose sealskins? Perhaps it is because of the color of the fur. Now these bindings look yellowish-gray or mottled brown. But they were originally white - some seals have almost snow-white skins. This color matched the monks' robes, so the snow-white bindings may have seemed magical to them.