Scientists have discovered the oldest sample of human DNA in the world in Europe (4 photos)

Thirteen bone fragments belonging to six people were found in a cave beneath the medieval castle of Ranis, Germany. The mother and daughter, along with their distant relatives, lived in Europe 45,000 years ago. Their sequenced genomes contain compelling evidence of encounters with Neanderthals.

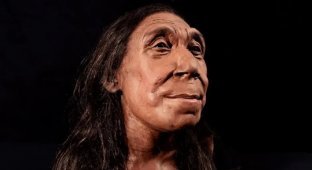

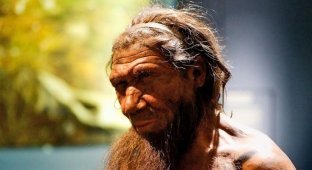

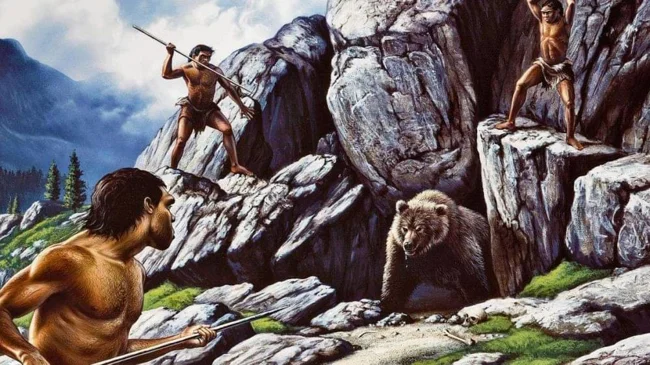

Illustration of ancient people from Germany and the Czech Republic

Genetic analysis has shown that the ancestors of these people, 80 generations before their birth, interbred with Neanderthals.

Since the Neanderthal genome was first sequenced in 2010, experts have known that ancient humans and Neanderthals interbred. This discovery laid the foundation for understanding the genetic legacy that continues to manifest in humans today.

However, questions remained about when, where, and how often this interbreeding occurred.

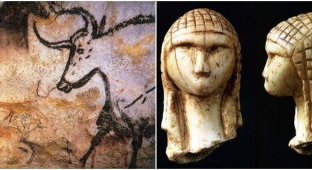

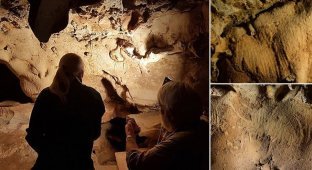

A cave system in the heart of the limestone region known as the Bohemian Karst, Czech Republic

The Ranis people were among the first representatives of Homo sapiens in Europe. An ancient woman from the Czech Republic's Zlatý Kun cave is also related to them. DNA from her skull was sequenced, and information about a related population was obtained.

Scientists suggest that the first interspecies contacts occurred in the Middle East. This is due to the fact that at that time Homo sapiens migrated from Africa and met Neanderthals.

Scientists recreate the face of an ancient woman whose skull was discovered in the Zlata Kun cave

Now, as part of a larger study, scientists have analyzed the genomes of 59 ancient people and 275 modern people. This analysis has provided a more precise timeline of events.

The study found that most of the Neanderthal ancestry of modern humans can be traced to a "single, long period of gene flow."

Over a 7,000-year period, early humans and Neanderthals mated and had children with reasonable regularity. The activity peaked around 47,000 years ago.

The genes inherited from Neanderthal ancestors now make up between 1 and 3 percent of our genome.

Some Neanderthal genes turned out to be very useful, especially those related to the immune system. This helped humans survive the last ice age.

One of the authors of the study, published in the journal Science, said: "We had more similarities than differences. We thought there were big differences between these groups, but from a genetic point of view, they turned out to be small."

Gene variants found in the genomes of both ancient and modern Homo sapiens are closely linked to certain characteristics and functions. These include immunity, skin pigmentation and metabolism.

However, it remains a mystery why people in East Asia have more Neanderthal ancestry than Europeans. It is also unclear why there are no obvious traces of Homo sapiens DNA in the genomes of Neanderthals from a certain period.