Bones of animals eaten by humans 45,000 years ago were found in Germany (7 photos)

The oldest remains of Homo sapiens in Central Europe were found in the Ilsenhöhle cave in Thuringia, Germany. The find suggests that small groups of modern humans began appearing in Europe as early as 45,000 years ago, gradually displacing Neanderthals.

1

The Ilsenhöhle Cave in Ranis (Thuringia, Germany), along with the Kents Cave, Lincombe Hill, Torquay (Devon, England) and the Jerzmanowice Cave in Ojcow (Krakow County, Poland) belongs to the so-called Lincombe-Ranisi-Jezmanowice (LRE) culture of the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic . About 40 different monuments of this culture have been identified.

Modern humans crossed the Alps into cold northern Europe about 45,000 years ago, meaning they may have coexisted with Neanderthals in Europe for thousands of years longer than previously thought, a new study says.

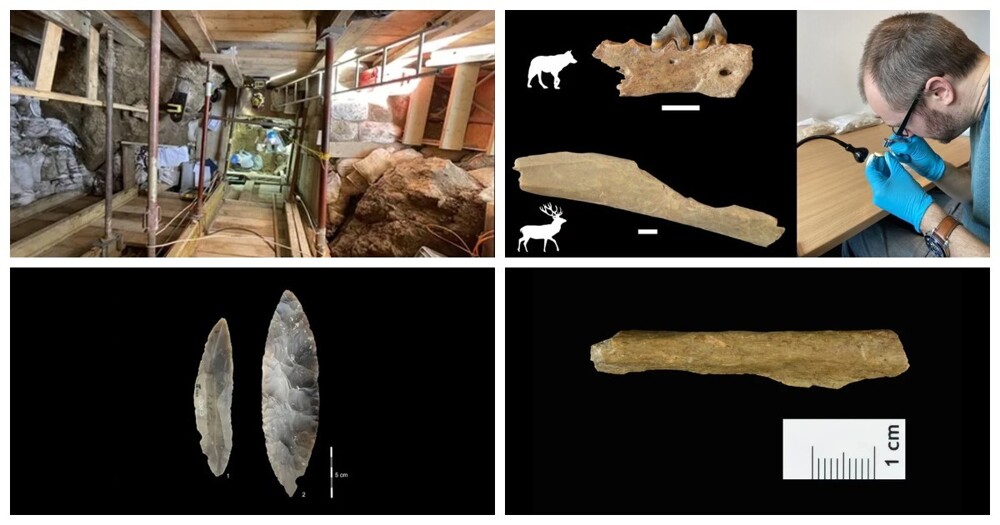

Excavation of the Lincombe-Ranisi-Jezmanowice (LRE) culture at a depth of 8 meters at Ranis was a challenging task and scaffolding was required to strengthen the trench

The discovery of 13 bone fragments belonging to Homo sapiens, who lived in a cave in Germany 44,000 to 47,500 years ago, is the oldest known remains of H. sapiens from Central and Northwestern Europe, researchers say. The find surprised scientists because, as they established, the climate in the region at that time was cold.

“This shows that even the early groups of Homo sapiens that dispersed across Eurasia already had some ability to adapt to such harsh climatic conditions,” Sara Pederzani, an archaeologist at the University of La Laguna in Spain and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, said in a statement. , who led the paleoclimate study at the site.

Early Homo sapiens processed deer carcasses as well as carnivores, including wolves, according to an analysis of more than 1,000 animal bones from Ranis

When H. sapiens arrived in Europe, they were not the first members of the human species to enter the continent. Neanderthals, our closest extinct relatives who were well adapted to the cold, lived in Europe from at least 200,000 years ago until their extinction about 40,000 years ago.

The period when H. sapiens entered Europe is called the transition from the Middle to Upper Paleolithic (47,000 - 42,000 years ago). Scientists are heatedly debating what the nature of the interaction between H. sapiens and Neanderthals was during this period and how much our species could have accelerated the extinction of Neanderthals.

To study this mysterious transition period, the scientists analyzed artifacts and the climate of the time, according to their findings published Jan. 31 in the journal Nature and in two studies in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Previously, archaeologists had discovered a number of different cultures, or styles of stone tool making, dating back to this period, including the Lincombe-Ranisiya-Jezmanowice, but it was unclear whether H. sapiens or Neanderthals created them.

“The Middle Paleolithic in Europe [about 300,000 to 35,000 years ago] is associated with Neanderthals, and the Upper Paleolithic in Europe [about 35,000 to 10,000 years ago] is associated with modern H. sapiens,” study co-author Jean-Jacques told Live Science Hublen, paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “The artifacts of the transitional period seem to have mixed features.”

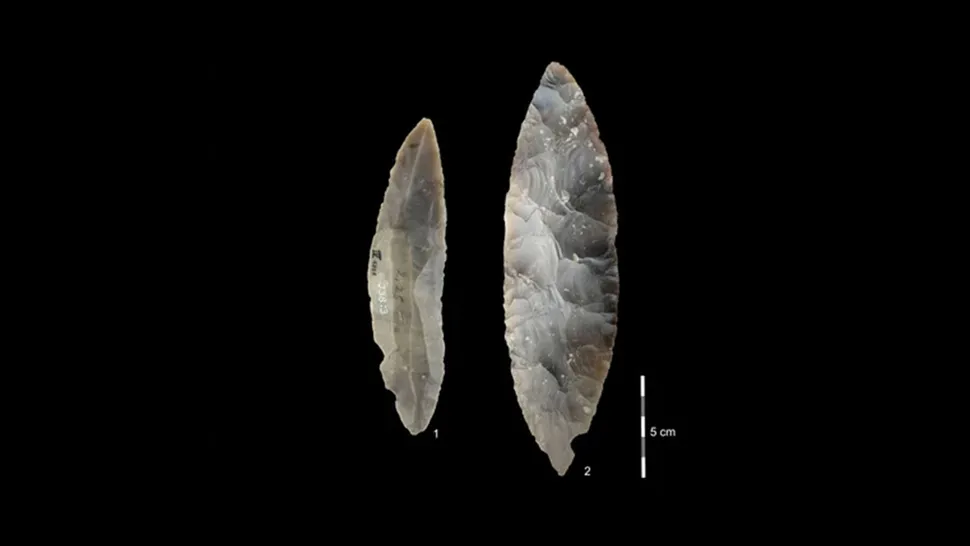

Stone tools, Ranis

In one of the new studies, scientists examined artifacts from the LRE culture, including elaborate leaf-shaped stone tools that were widespread in northern Europe from Germany to Britain.

Scientists examined thousands of bone fragments associated with LRE artifacts at Ilsenhöhl (Ilse's Cave) in Ranis, Germany. They not only conducted new excavations at the site, but also re-analyzed the remains found in the cave in the 1930s and now housed in museum collections.

One new study found that the cave was periodically used not only by hyenas and cave bears, but also by small groups of hominins—likely H. sapiens or Neanderthals—that fed on reindeer, woolly rhinoceroses and horses. However, many of the bone fragments were too small and broken for researchers to identify.organize them according to form. Analysis of proteins and DNA extracted from these remains helped determine their origin.

As a result of the study, scientists concluded that 13 bone fragments date back to a period of approximately 44,000 - 47,500 years ago.

Human bone fragment, Ranis

“The conventional wisdom is that these artifacts were made primarily by late Neanderthals,” says Hublen. “In the case of the LRE culture, we discovered that they were not made by Neanderthals, but by Homo sapiens, who moved to Europe much earlier than we thought.”

Analysis of teeth and animal bones from the cave suggested that when people lived there, the climate in the region was very cold, with steppe or tundra landscapes - similar to those found today in Siberia or northern Scandinavia.

Ilse Cave (Ilsenhöhle) is visible under Ranis Castle.

“Until recently, resistance to cold climates was thought to only emerge after several thousand years, so this is an interesting and surprising result,” Sarah Pederzani said in a statement. “Perhaps the cold steppes with large herds of predatory animals were a more attractive environment for these human groups than previously thought.”

After chemical preparation and cleaning, very small samples of animal teeth are loaded into a mass spectrometer to obtain stable oxygen isotope ratios. It can provide information about the climate in which animals lived in the past.

This evidence suggests that H. sapiens appeared in northwestern Europe several thousand years before the extinction of Neanderthals in southwestern Europe, suggesting that the two groups may have interacted. "We now have another important piece of the complex puzzle regarding the nature of the interaction between H. sapiens and Neanderthals," said William Banks, an archaeologist at France's National Center for Scientific Research who was not involved in the study but wrote a paper about it.

“These results suggest that H. sapiens did not replace Neanderthals in Europe in a rapid east-west wave, as previously thought. We see that Homo sapiens first colonized the northern part of Europe and lived there for several millennia on the periphery of the Neanderthal world,” says Hublen. “I would say that Homo sapiens probably lived in these rather hostile environments because they had the technical capabilities to adapt there.” We see not one wave of Homo sapiens coming into Europe and displacing the Neanderthals, but successive impulses of small groups that moved into new territories and then, after a few millennia, displaced the Neanderthals completely.”