Scientists have discovered new evidence of life on Mars (4 photos)

Researchers have discovered a 2,896-km-wide plain in the northern hemisphere of the Red Planet, where underground conditions are favorable for the existence of organisms. The soil of the region, known as Acidalia Planitia, contains enough water, heat, and energy for bacteria to survive.

Acidalia Planitia

The next step will be to drill into the Martian surface to see if life really did start there.

"This is a promising area for future missions to search for surviving life in the interior of Mars," write the researchers, led by Andrea Butturini of the University of Barcelona.

However, researchers will have to delve kilometers into the interior of the Red Planet. This will require large-scale expeditions and technologies that will only be available in the distant future.

Nevertheless, this discovery brings scientists closer to definitive proof of the existence of life beyond our planet.

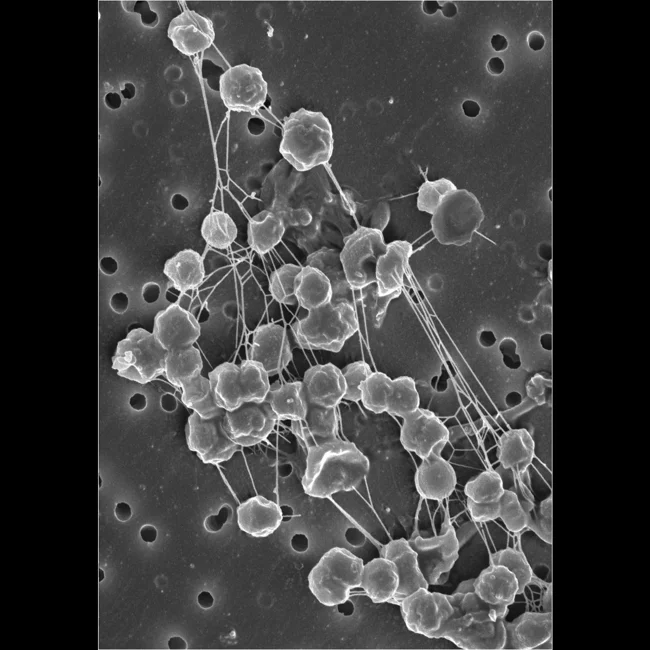

The life forms that may live beneath Acidalia Planitia are methanogens, or bacteria that produce methane.

Methanogens are extremophiles, bacteria that can thrive in extreme environmental conditions.

On Earth, methanogens are typically found in swamps, but they can be found in the guts of cows and other herbivores, as well as in dead and decaying organic matter.

These microorganisms are anaerobic, meaning they do not require oxygen to survive. They can survive without organic nutrients or sunlight.

Extremophiles are bacteria that can thrive in extreme environmental conditions

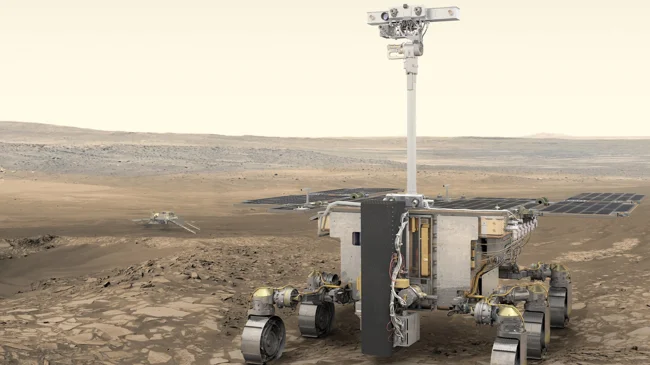

In 2028, the European Space Agency (ESA) plans to launch the Rosalind Franklin rover, formerly known as ExoMars. It is equipped with a drill capable of going 2 m into the surface. Butturini and his colleagues have determined that this is not enough.

The Martian surface is inhospitable due to extremely low temperatures and low pressure, in which even extremophiles cannot survive.

However, in the depths, the decay of elements such as thorium, a radioactive metal, releases heat and chemical energy. Moreover, there is water left over from ancient oceans.

These conditions could create a favorable environment for bacteria to live, but probably only at a depth of 8 km.

In 2028, the European Space Agency (ESA) plans to launch the Rosalind Franklin rover

Biogeochemist Butturini and his colleagues analyzed data from orbiters to identify areas with sufficient thorium concentrations. They then compared this data with the distribution of subsurface ice previously mapped by devices such as China's Zhurong rover.

The analysis revealed that the most suitable area is the southern part of Acidalia Planitia. The temperature in its depths is higher than on the surface, averaging between 0 and 10°C. This means that there could be water in the ground. And where there is liquid water, bacterial life could thrive.