The unique gym of Dr. Gustav Sander and exercise machines that have become the highlight of the Victorian era (18 photos)

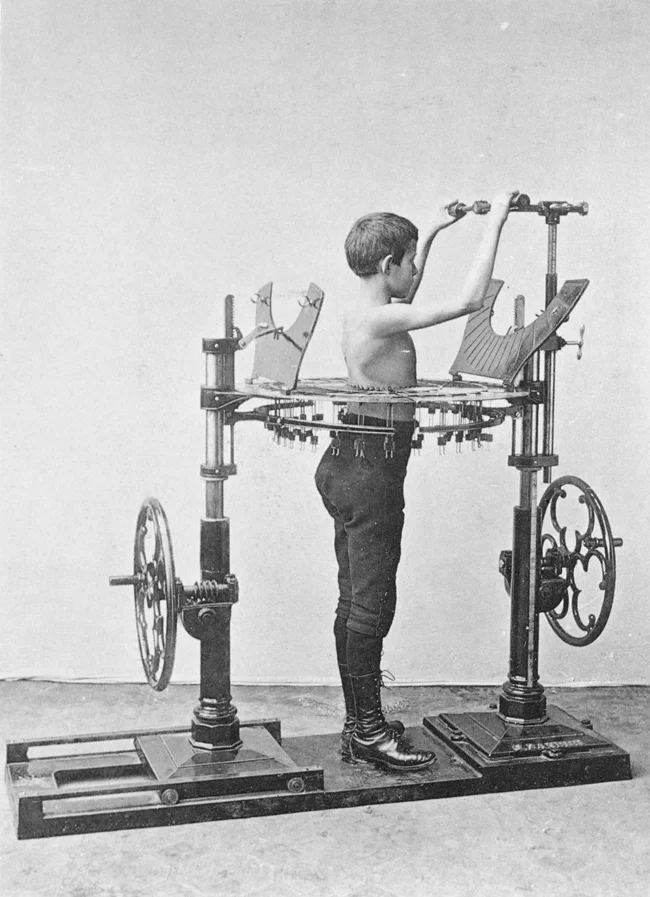

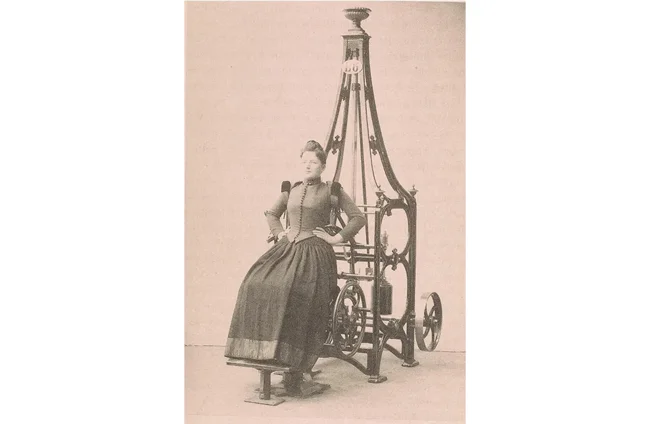

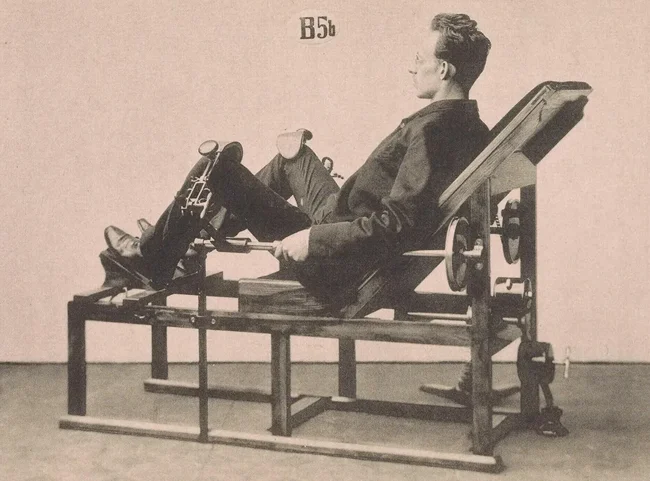

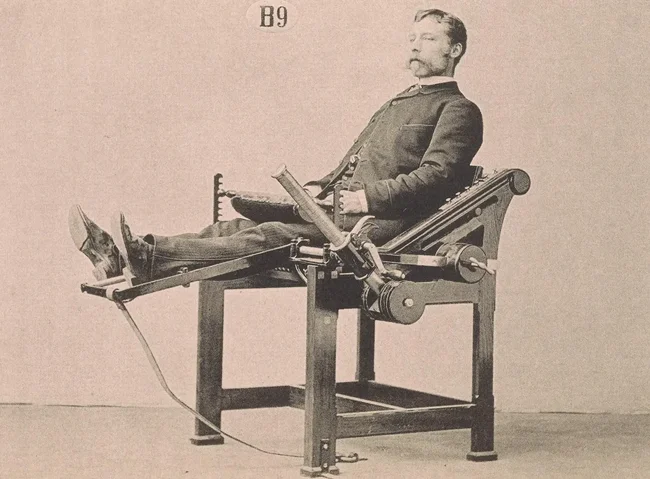

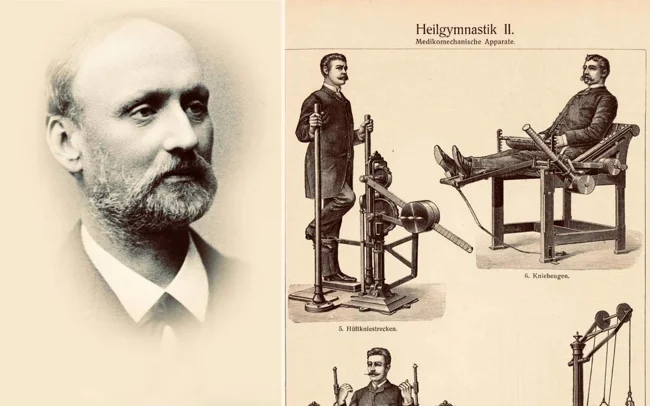

Dr. Gustav Sander's Institute in Stockholm, founded in 1865, could be called the world's first gym. It was equipped with 27 custom-made machines, which Sander's patients used.

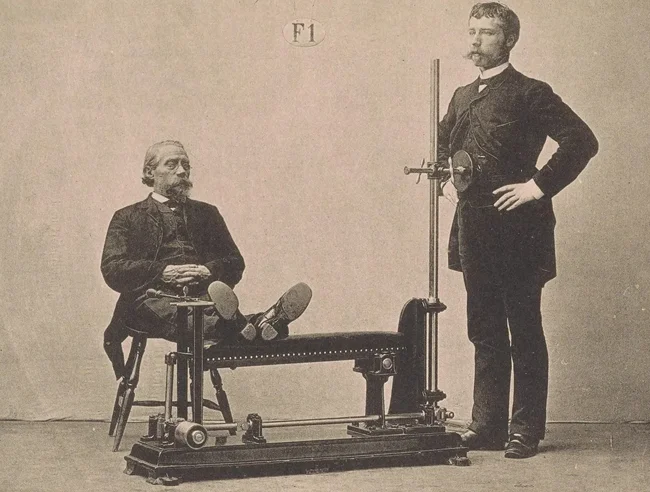

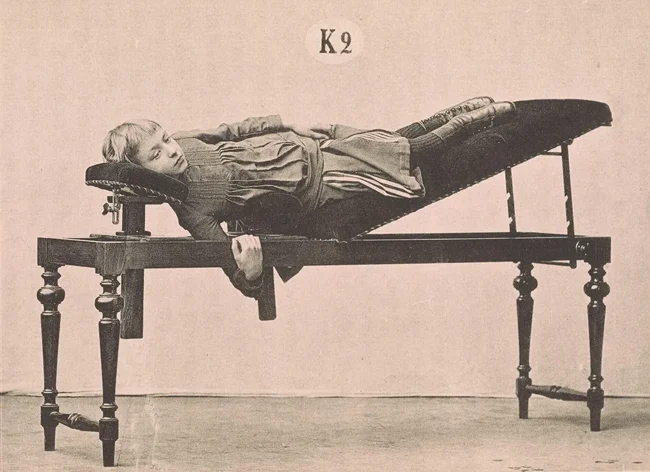

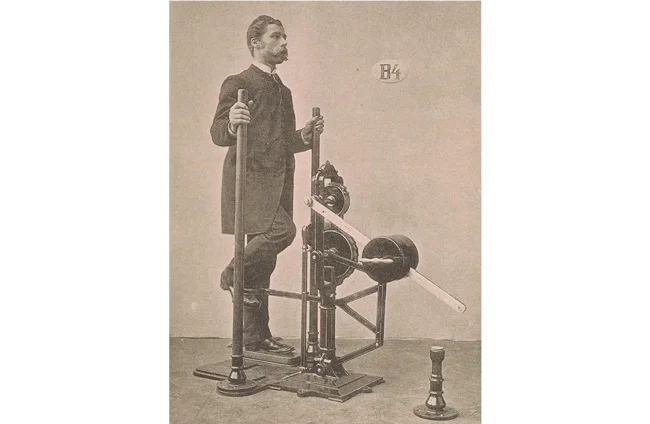

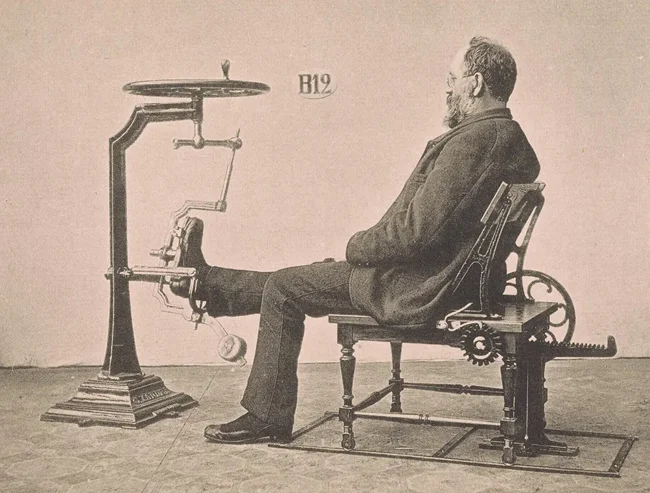

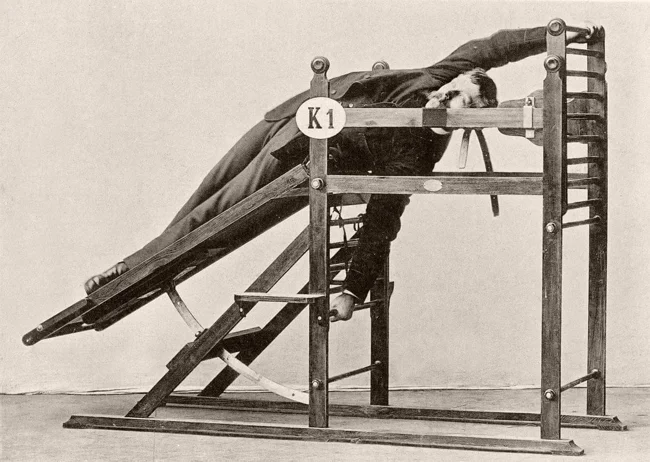

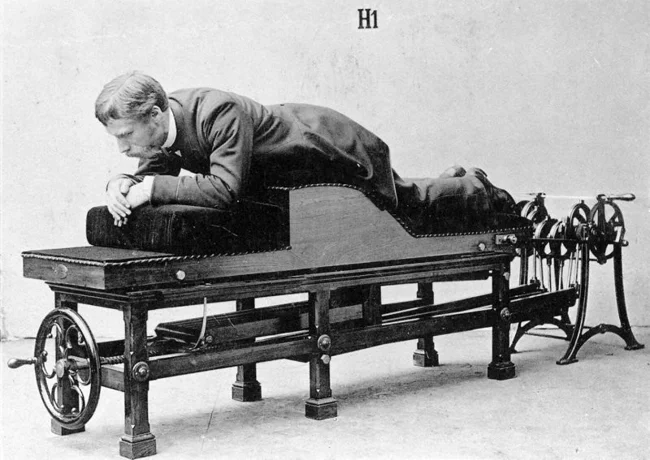

Sander claimed that his therapeutic machines could correct a range of physical deficiencies, disabilities, and ailments resulting from birth accidents or hard labor. A follower of the healing movement promoted by earlier exercise pioneer Per Henrik Ling, Zander argued that the key to health was not strenuous acrobatics but "progressive loading" - the controlled, systematic use of the body's muscles to build strength.

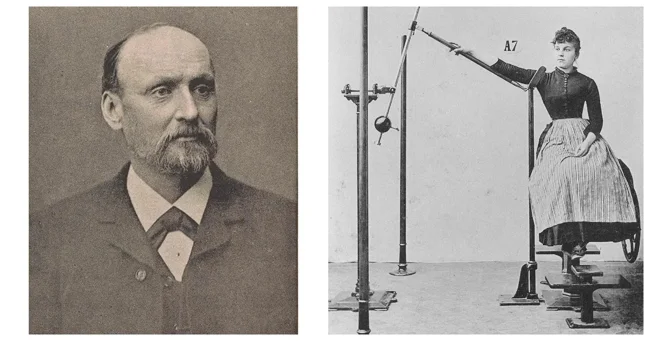

Gustav Zander

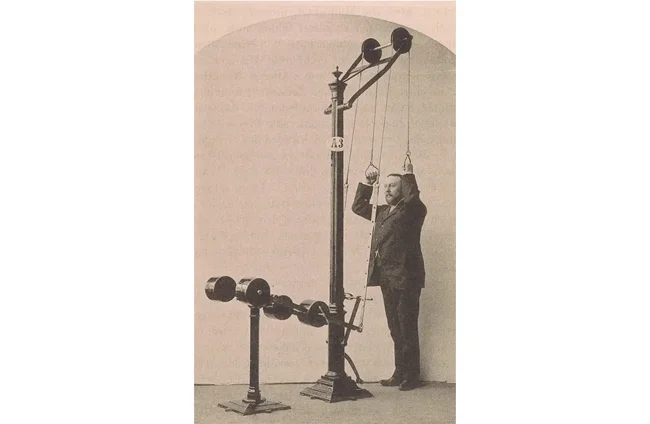

Shortly after receiving his medical license in 1864, Zander put his ideas into practice at a local Stockholm school, creating a prototype therapeutic exercise machine for students. The machines used weights and levers that could be pulled and moved to adjust the resistance based on each person's strength. Another set of weights and levers compensated for the weight of the user's body or limbs. The motorized machines prevented the muscles of those suffering from paralysis or extreme weakness from atrophying.

After noticing significant improvements in the strength and health of his subjects at the Stockholm school, Zander opened the Medico-Mechanical Institute in Stockholm to promote his machines. At first, medical practitioners were skeptical of the claims of the new therapy, but as evidence of improvement in patients' conditions emerged, more and more medical practitioners around the world endorsed Zander's therapy, leading him to open a second Zander Institute in London.

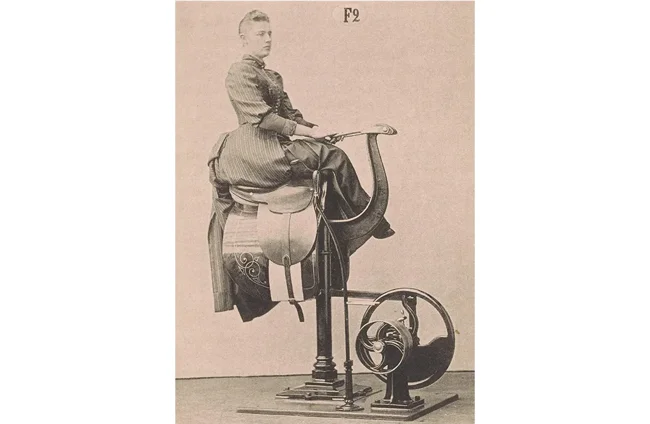

Zander's machines were a sensation at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial International Exposition, winning an award for best design. The rapid mechanization brought on by industrialization in the latter half of the 19th century had led to an increase in office workers, and Zander began marketing his machines to this rapidly growing business class. Zander explained to audiences that his machines were "a prophylactic against the evils of sedentary life and the seclusion of the office."

By the turn of the century, his machines could be found in health centers across the country, as well as in private institutions such as the one Zander established near Central Park in New York City. Access to these health machines was a sign of status that reflected a person's free lifestyle and liberation from physical labor.

After Sander's death in 1920, his devices and his contributions to physical therapy were largely forgotten until these radical ideas were rediscovered in the last decades of the 20th century. Now his revolutionary ideas are once again receiving the attention and respect they deserve.