People think that flying a plane during the day is easier because they can see where they are going.

But flying a plane is very different from flying a car, and is much more precise. It has a sophisticated navigation system that allows the pilot to fly without a visual reference, relying entirely on the instruments. This is known as instrument flight rules, and commercial pilots often follow them when flying, such as when flying through clouds or at night.

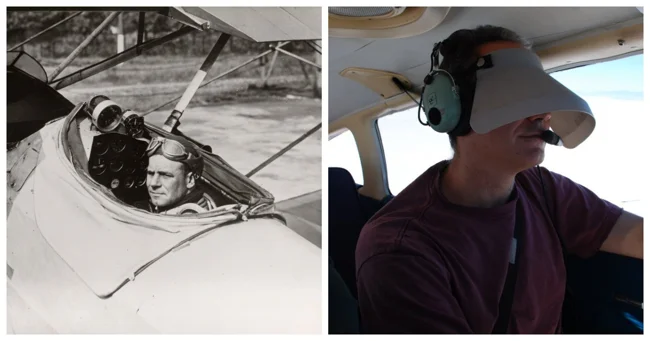

Jimmy Doolittle

Instrument flying, or blind flying, was first demonstrated by aviation pioneer Jimmy Doolittle in 1929. At the time, Doolittle was one of the few outstanding pilots. During World War I, he was a flight instructor and reserve officer in the United States Army Air Corps. He was called to service, where he received the Medal of Honor for his daring raid on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Doolittle was also one of the first pilots to fly coast-to-coast in the United States, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. However, his greatest contribution to aviation technology was the introduction of instrument flying.

Doolittle was the first to recognize that true freedom of action in aviation could only be achieved if pilots could control and fly an aircraft from takeoff to landing, regardless of visibility limitations. He envisioned that pilots could be trained to use instruments to fly in a variety of weather conditions and situations where visual cues were unavailable. As aircraft became faster and more maneuverable, pilots increasingly ran the risk of becoming disoriented without external visual references, since their senses could not accurately interpret motion.

Doolittle pioneered the study of the relationship between the psychological impact of visual cues and the sense of motion.

His research resulted in programs that taught pilots to understand navigational instruments. His work taught pilots to ignore what they "felt" and trust their instruments, since visual and sensory cues could be incorrect or unreliable.

Doolittle's experiments with blind flying began in 1926, when wealthy industrialist and philanthropist Daniel Guggenheim founded the Foundation for the Advancement of Aeronautics and its Total Flight Laboratory at Mitchell Field. Like Doolittle, Guggenheim also believed that if aviation instruments could be improved and radio communications could be added, the mysteries of bad-weather flight might be solved.

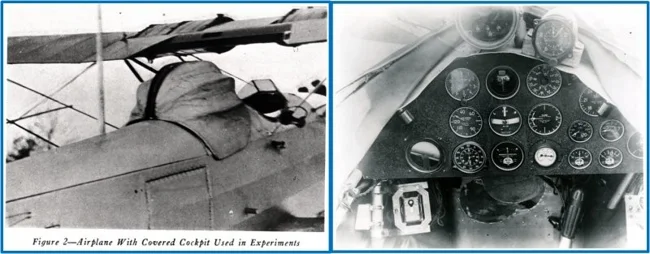

The cockpit of Doolittle's blind flight NY-2 Husky

The laboratory experimented with various instruments and came to the conclusion that an artificial horizon (a small instrument indicating the longitudinal and lateral position of the aircraft relative to the ground) and a gyroscope informing the pilot of the course were the right combination for control. And a sensitive barometric altimeter was so thin that it could measure the height of the aircraft several meters from the ground. These three instruments would soon become universal.

On September 24, 1929, Doolittle and his pilot Ben Kelsey boarded a heavily modified NY-2 Husky. In addition to the gyroscope, artificial horizon, and altimeter installed in the cockpit, Doolittle received additional heading information from a radio rangefinder aligned with the airport runway, and radio beacons indicated his distance from the runway.

To prevent Doolittle from "cheating," a hood was installed over the pilot's cabin, completely blocking him from any view of the outside world and forcing him to rely only on his instruments and radio. The check pilot was there only to intervene in an emergency. However, Kelsey had to hold his hands high above his head so that everyone could see that he was not flying the plane.

Doolittle took off without difficulty, circled the airfield, crossed it, crossed it again, and then landed a short distance from the takeoff point. The flight took only 10 minutes, but those minutes proved that the plane could only be flown by instruments.

After the flight, Doolittle said with an embarrassed grin: "Despite all my previous practice, the approach and landing were sloppy. As far as I know."

In 1989, to mark the 60th anniversary of the flight, a sculpture of Doolittle was unveiled near Jimmy Doolittle's hangar at the former Aircraft Radio Corp. airfield in Boonton, New Jersey, where Doolittle consulted with ARC experts many times during the Total Flight Laboratory experiments.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: