Sad story of the killer whale Ethelbert (7 photos)

Killer whales have a huge habitat, inhabiting all the world's oceans.

In the northeastern Atlantic, they are found in abundance off the Norwegian coast, and in the northern Pacific Ocean - near the Aleutian Islands and in the Gulf of Alaska.

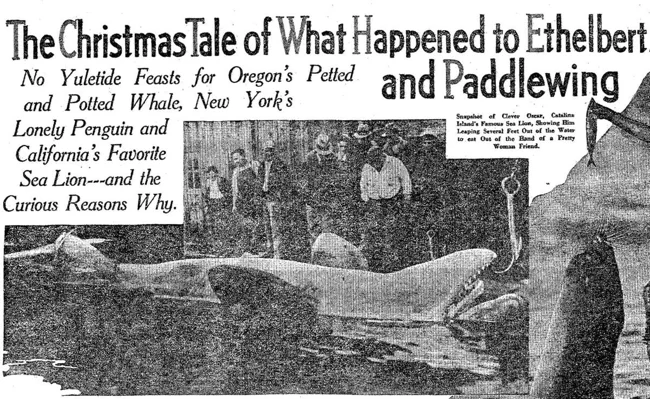

One of the whale-human encounters that quickly turned tragic occurred in October 1931, when a young orca swam up the Columbia River and surfaced in Columbia Bay, a narrow channel that runs parallel to the Columbia River north of Portland. The orca was spotted near the city's popular amusement park, Jantzen Beach, and thousands of Portlanders gathered to catch a glimpse of the unexpected visitor. The crowds of people eager to see the stunning creature caused a traffic jam on the Portland-Vancouver bridge. Local newspapers covered the event on their front pages, and vendors took advantage of the opportunity to set up kiosks selling simple food. Boatmen invited spectators to come closer to the animal.

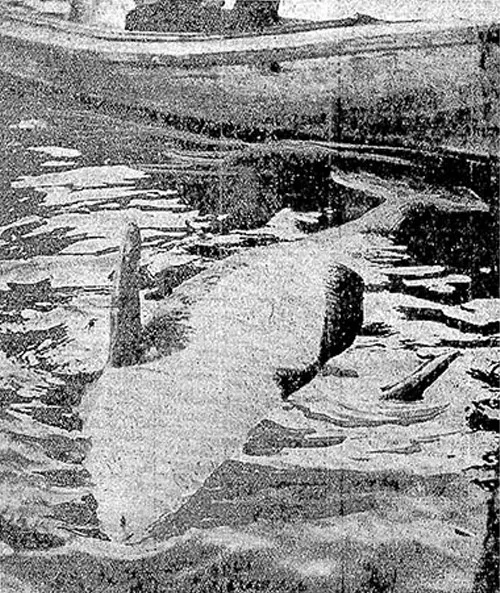

Ethelbert after the kill

The killer whale also attracted ill-wishers. Some even tried to shoot the animal with rifles. They were immediately arrested, and the governor ordered that the animal be protected.

Given the attention from the press, it became necessary to give the killer whale a name. For a time, the animal was called the Jimmy McCool whale, after a wildlife journalist from The Oregonian, but most people and media outlets eventually settled on the name Ethelbert, meaning "noble."

For two weeks, there was intense debate in the press and government agencies about the fate of the animal. Many wanted to capture the orca alive and put it on display in an aquarium. The Oregon Society opposed this idea, believing any capture to be inhumane. Instead, they believed that the orca should be euthanized to end its suffering, as it was clearly dying. The waters of Columbia Bay were not suitable for the orca, as they were desalinated and contaminated by sewage. In addition, the gunshot wounds on his back had become infected. Others suggested leaving Ethelbert alone to let nature decide its fate.

There were also those who sincerely wanted to save the animal. The same James McCool wrote in The Oregonian that "a string of tugs and motorboats" with "whistling and ringing bells" could be used to drive the whale into the Columbia River, from where it could reach the Pacific Ocean.

While authorities debated the viability of the plan, a former whale hunter named Edward Lessard and his son Joseph boarded a boat and killed Ethelbert with a harpoon:

It was the fastest kill I've ever seen. It usually takes half a day or a day to kill a whale. This one was dead as a doornail in less than five minutes, Lessard bragged to The Oregonian.

The Portland community was outraged. This was unconscionable destruction of wildlife, and it must be punished. The Lessards were charged with violating the fishery laws and "outraging public decency and morality."

Although the men were arrested, the state was unable to bring charges against them because it was determined that they had not violated the fishery laws since Ethelbert was not technically a fish. While Lessard was in jail, a group of unscrupulous fishermen salvaged the body from the river bottom, dragged it to shore, and began charging spectators to watch it. Eventually, the police broke up the home-grown businessmen and confiscated the whale, and a large metal tank was hastily constructed to preserve it in formaldehyde.

The court, while acquitting the Lessards of liability, ordered the state to return the whale to the Lessards, who immediately went on a tour with it.

The state appealed the court's decision to the Oregon Supreme Court. The state attorney argued that since there were no laws regulating whaling in inland waters, the Lessards should rely on common law, which held that freshwater whales were "royal fish" and therefore the property of the governor. The court agreed, and ordered Lessard to return the whale to the state or pay $1,000.

For four years, Edward Lessard stubbornly held on to the whale's remains, refusing to give them up. Finally, the Oregon Board of Control offered a solution: they would drop the case if Edward Lessard agreed to pay the legal fees, which amounted to approximately $103. Without hesitation, Lessard paid the amount, securing legal title to Ethelbert's remains.

In 1939, the Lessards moved the whale to an orchard they owned near St. Helens, Washington. Ethelbert disappeared from public view and was largely forgotten until 1949, when neighbors complained of a putrid odor emanating from the orchard. Upon inspection, police discovered a rusting galvanized steel tank containing the unfortunate Ethelbert.

The tank was originally full of embalming fluid, but rust had caused holes in it and the fluid began to leak. Without the formaldehyde that had preserved Ethelbert for nearly 20 years, the carcass began to decompose. The Lessard family buried the remains in a wooded area. After 30 years, logging inspectors found the remains and reburied the long-suffering orca on a mountain.