Optografia: The Last Look Before Death (14 photos)

In 1924, Germany was rocked by a sensational case of multiple murders. Fritz Heinrich Angerstein, a resident of Limberg, brutally murdered his family, including his servants, in a failed suicide attempt.

Angerstein's horrific actions began with the murder of his wife, followed by a failed suicide attempt on his part. He then turned his anger on his mother-in-law, justifying his actions by saying that she had mistreated his sick wife.

Angerstein didn't stop there: he also killed his maid, which he later claimed was due to her culinary failures and general disapproval of her behavior. By the time the massacre was over, Angerstein had killed eight people, including his sister-in-law, an accountant, a clerk, a gardener, and his assistant.

At first, Angerstein claimed that he had been attacked by bandits who had killed everyone in the house and left him for dead. However, as the investigation progressed, doubts began to emerge about Angerstein's story. He was unable to explain why his fingerprints were found on the murder weapon and why there were no signs of robbery. In addition, there were many contradictions in his testimony.

Angerstein was arrested and charged with murder, which he denied. Then one of the police officers came up with irrefutable evidence: a professor at the University of Cologne managed to photograph the retinas of two victims, on which images of Angerstein with raised hands, clutching an axe, were found. When Angerstein learned about the photographs, he gave in and confessed to the crime. Angerstein's case is the only example, albeit a very dubious one, when a conviction was made thanks to an optogram - an image on the retina.

The "Science" of Optography

For a long time, scientists have wondered whether it is possible for the eye to capture an image of our last vision at the moment of death. The idea was first put forward in the 17th century by the Jesuit monk Christopher Schiner, who claimed to have noticed a faint image on the retina of a frog he was dissecting. However, it was not until the invention of photography in the 1840s that optography became a scientific endeavor.

Franz Boll (physiologist)

Scientists reasoned that for the retina to act like a camera plate, it must contain some light-sensitive chemicals, similar to the silver nitrate film that coated the glass slides on which the earliest photographs, daguerreotypes, were taken. In 1876, German physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered rhodopsin, a light-sensitive protein in the rod cells of the retina that behaves just like the nitrate on a camera plate: it bleaches when exposed to light.

Boll's life was cut short at the age of thirty, a victim of tuberculosis, which prevented him from pursuing his research further. However, his contributions were enough to convince the scientific community that changes in rhodopsin played an important role in the ability to see.

After Boll's death, one of his admirers, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne, took up Boll's discoveries. Kühne began experimenting on numerous animals, removing their eyes immediately after death and exposing them to various chemicals to fix the image on the retina. Kühne found that alum worked best.

Wilhelm Kuehne

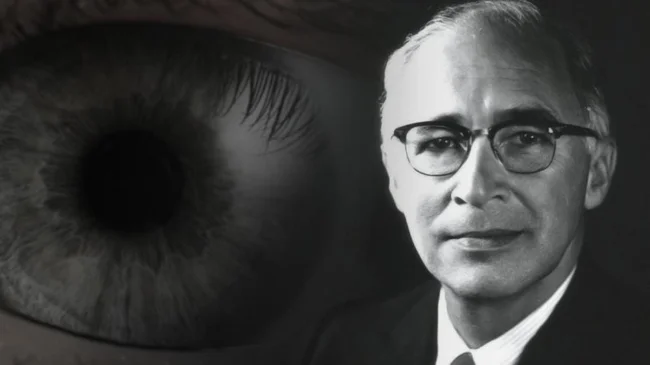

Biochemist George Wald, a Nobel Prize winner for his studies of visual pigments, describes one of Kuehne's most successful experiments with an albino rabbit:

The albino rabbit was tied by its head to a barred window. From this position, the rabbit could see only a gray and cloudy sky. The animal's head was covered with a cloth for several minutes so that the eyes adapted to the darkness, that is, so that rhodopsin accumulated in their rods. Then the animal was exposed to the light for three minutes. He was immediately beheaded, his eye was removed and cut open, and the back half of the eyeball, containing the retina, was placed in an alum solution for fixation. The next day, Kuehne saw an image of a window with a clear pattern of its lattices imprinted on the retina in bleached and unaltered rhodopsin.

Biochemist George Wald

Kuhne rabbit optograms. The leftmost image is the rabbit's retina without an optogram: the light disk and horizontal stripe across the upper third of the retinal image are normal anatomical features of the retina. The central image is an optogram obtained after the rabbit was exposed to light. The window to which the animal was facing is clearly visible in the picture. The rightmost image is another optogram, which shows three large windows located next to each other.

Drawing by Kuehne of an optogram taken from an executed criminal in 1880

Kuehne was eager to demonstrate this technique on a human, and in 1880 the opportunity presented itself. On November 16, Erhard Gustav Reif was executed by guillotine for the murder of his children in the nearby town of Bruchsal. Reif's eyes were removed within ten minutes of the execution and taken to Kuehne's laboratory at the University of Heidelberg. The optograms that Kuehne made from Reif's eyes have not survived, but a sketch of them appears in Kuehne's Observations on the Anatomy and Physiology of the Retina, published in 1881. It does not resemble anything the victim could have seen at the time of his death. However, it has been suggested that the drawing bears a superficial resemblance to a guillotine blade, although the victim could not have seen it because he was blindfolded. Others have suggested that it may be steps leading up to a platform.

Despite Kuhne's failure to obtain a proper optogram from a human eye, the idea of preserving the last visual images of a dead person continued to hold sway over the Victorian imagination. When it was suggested that optograms could be obtained from murder victims to help identify their assailants, the French Society of Criminology became concerned and asked Dr. Maxime Vernoy to conduct a study to examine the admissibility of optograms as evidence in murder trials. Vernoy killed no fewer than seventeen animals and dissected their eyes, but to no avail. He later noted:

"It is impossible to find on the retina of the victim's eye a portrait of her murderer or an image of any object or physical feature that was present to her at the moment of death."

Despite Vernoy's conviction and Kuehne's failed experiments, investigators continued to take photographs of the eyes of murder victims, hoping that such images would help solve criminal cases.

In 1877, when an elderly woman, Frau von Sabatzky, was murdered in Berlin, police photographed her eyes shortly after she was found, but the images yielded no clues. Eyeball photography was also considered very seriously in the United States, for example in the double murder of Laura Shearman and Cynthia Davis, the Villisca axe murder of 1912, and the murder of Tracy Hollander in 1914. Detectives investigating the Jack the Ripper murders in Britain in 1888 also suggested trying the technique on the Ripper's victims.

Still from the film "The Invisible Ray"

Popular science fiction writer Jules Verne also immortalized the idea that the science of optography could have forensic potential in his 1902 novel "The Brothers Kip." Over the next hundred years, the idea would be repeated frequently in literature and media. The 1936 film "The Invisible Ray" features a scene in which Dr. Felix Benet, played by Lugosi, uses an ultraviolet camera to photograph a victim's dead eyes. Optography was also used as a plot point in the 1971 Italian film Four Flies on Grey Velvet and in a 1975 episode of Doctor Who.

The idea was so common that some killers even went to great lengths to destroy their victims' eyeballs, as in the 1927 murder of police officer George Gutteridge, an unarmed policeman who was brutally shot through both eyes. In another case, in 1990, a woman in Alsace murdered her mother-in-law and then gouged out her eyes in an attempt to destroy evidence.

By the beginning of the 20th century, investigators had lost hope that optography could be turned into a useful forensic technique.

Despite this, in 1975 the Heidelberg police approached Heidelberg University specialist Evangelos Alexandrides to re-analyze Kuehne's experiments and findings using modern scientific methods, updated knowledge and advanced equipment. Alexandrides, like Kuehne, managed to obtain several clear, high-contrast images from the rabbits' eyes. However, he came to the final conclusion that optography had no potential as a forensic tool. This was the last example of serious scientific research in the field of optography.