Was there a boy? More precisely, in this case, the kidnapping of an ordinary maid. Although history is a thing of the past, it continues to arouse the interest of inquisitive minds with its inconsistencies and confusion despite its apparent simplicity.

On January 1, 1753, an ordinary London servant named Elizabeth Canning disappeared while returning home. In the following days, searches for her mother and employer yielded nothing.

18th century London

On January 29, Canning showed up at her mother's doorstep. The girl was exhausted and her clothes were in poor condition. She was not immediately able to tell her mother what happened to her.

What happened? Elizabeth Canning version

Elizabeth Canning

Ultimately, she stated that she was returning home in the early hours of the 2nd when two men hit her in the head. An unconscious Elizabeth was taken to a house where an old lady told her that she wanted the girl to prostitute herself for her. Canning refused. Then the old woman hit the girl in the face, cut off the strings from her corset and locked her in the attic.

Canning was able to give a clear description of her captors and the attic that served as her prison. She managed to escape by tearing off the boards covering the window. She stated that one of the kidnappers had the last name Wells or Wills.

Investigation

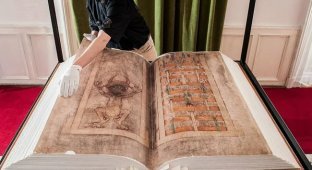

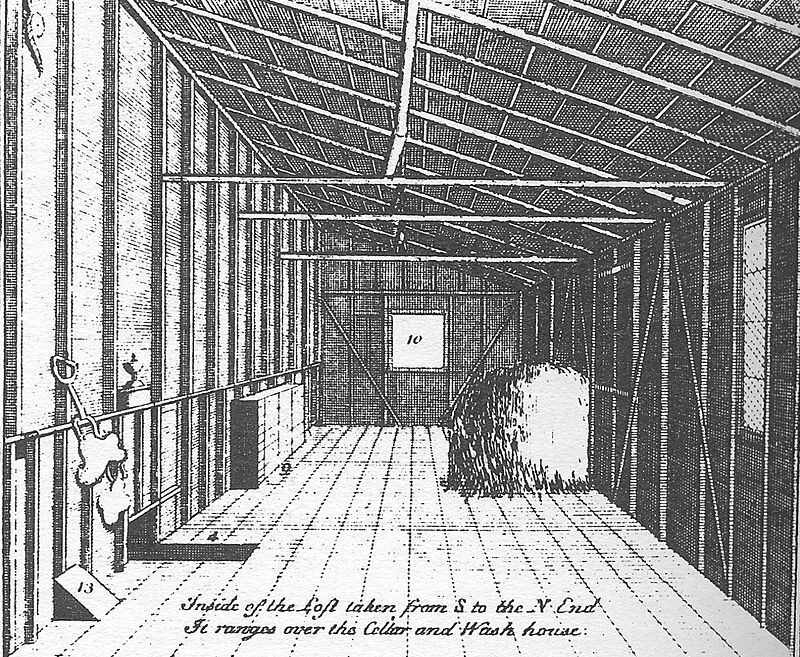

Elizabeth's description of the house and attic

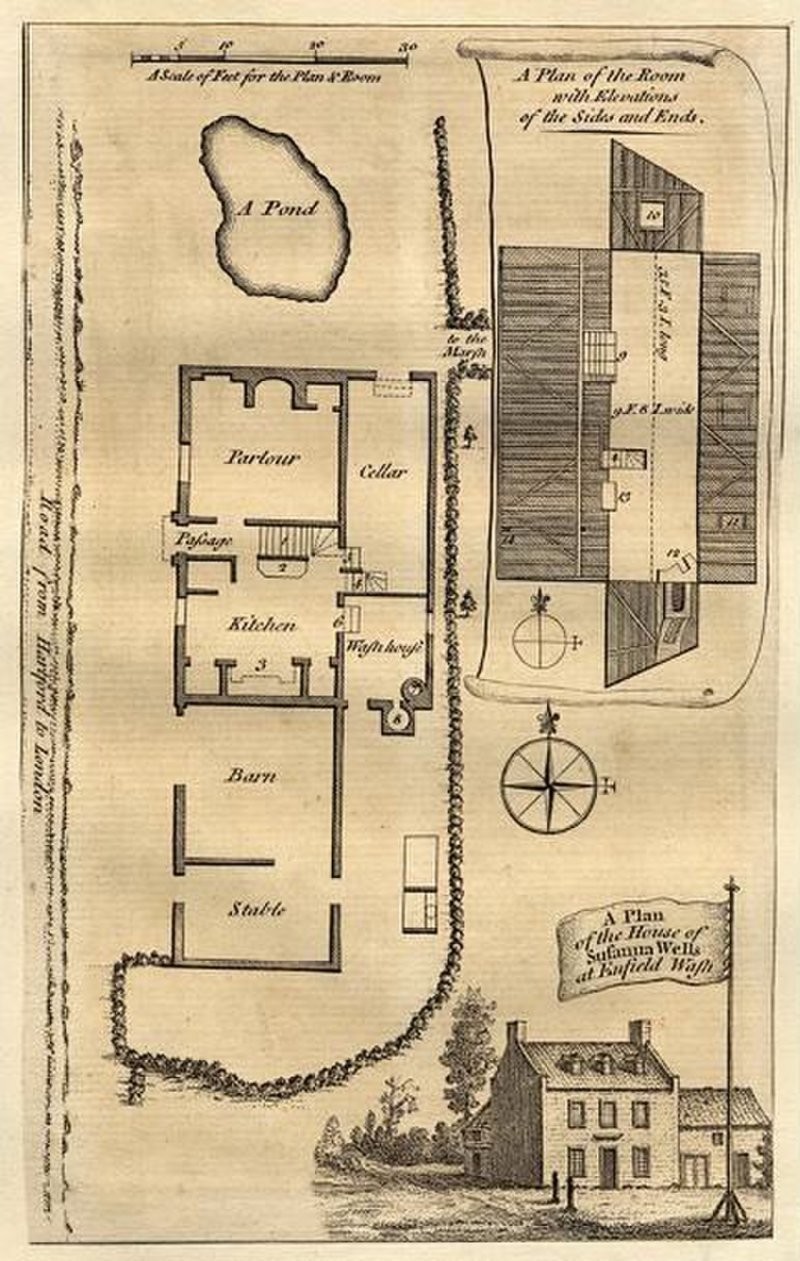

The police were called and Canning was questioned long and hard. It was determined that Suzanne Wells and her family lived in the house. The house was located about 16 kilometers from Canning’s mother’s place of residence.

On February 1, still very weak, Canning went to Wells's house, accompanied by local authorities. The girl named Wells and another woman in the house, Mary Squires, as her kidnappers.

The investigation began, but soon reached a dead end. An officer who examined the attic of the house found it to be completely different from Canning's description. In addition, all the boards on the windows were in place.

Henry Fielding

Wells and Squires were taken into custody, although they loudly proclaimed their innocence.

The investigation was led by Henry Fielding. After meeting with Canning several times, he believed the young woman and began the process of presenting a legal case against the detainees. Oddly enough, the kidnapping and attack on Canning did not require any special punishment at that time, but the theft of corset elements could lead to the gallows.

Newspapers closely followed the development of this story. Wells and Squires were declared gypsies. Belonging to this ethnic group at that time caused particular condemnation.

Under pressure from authorities, a woman living in Wells' house named Virtue Hall admitted that she knew about the illegal imprisonment.

Trial

A maid was supposedly kept here

Justice was done quickly. On February 21, Wells and Squires appeared in court. The Lord Mayor of London himself presided. Canning testified about her abduction and stay in the attic, where she lived only on bread and water. The defense presented numerous witnesses who stated that the accused women were not in the area at the time in question. The arguments sometimes coincided, sometimes diverged. In the end, the case reached the jury, which found both women guilty.

Where is the proof?

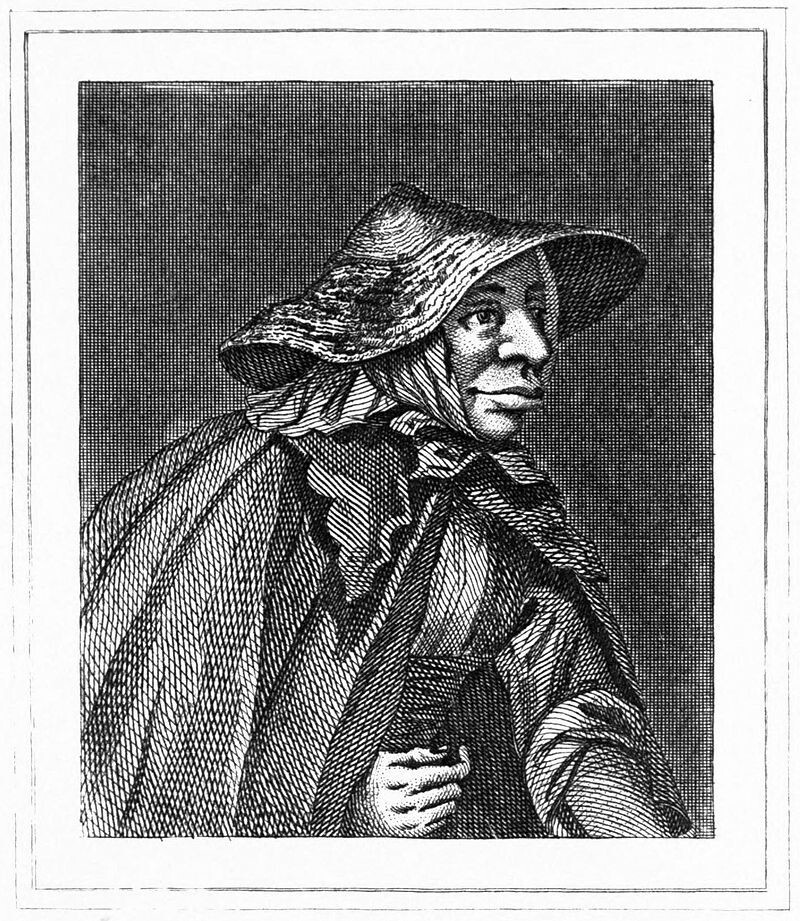

Portrait of Mary Squires

The people of London rejoiced at the verdict. But the judge, Sir Crisp Gascoigne, was not particularly happy. He began his own investigation based on gross inaccuracies in Canning's story. In addition, more witnesses came forward to say that Squires was not near Wells' home at the time of the crime. In an interesting twist, Virtue Hall, whose confession was instrumental in the conviction, recanted it.

Reversal of conviction and perjury charge

Judge Crisp Gascoigne

Enough evidence was collected and Canning was soon arrested for perjury. Wells and Squires were released.

At this point, it was difficult to say who said what, who accused whom of what crime, and which testimony turned out to be compelling and which was smashed to smithereens.

At Canning's trial, both Virtue Hall's revised testimony and evidence contradicting Canning's version of the crime were presented.

Guilty?

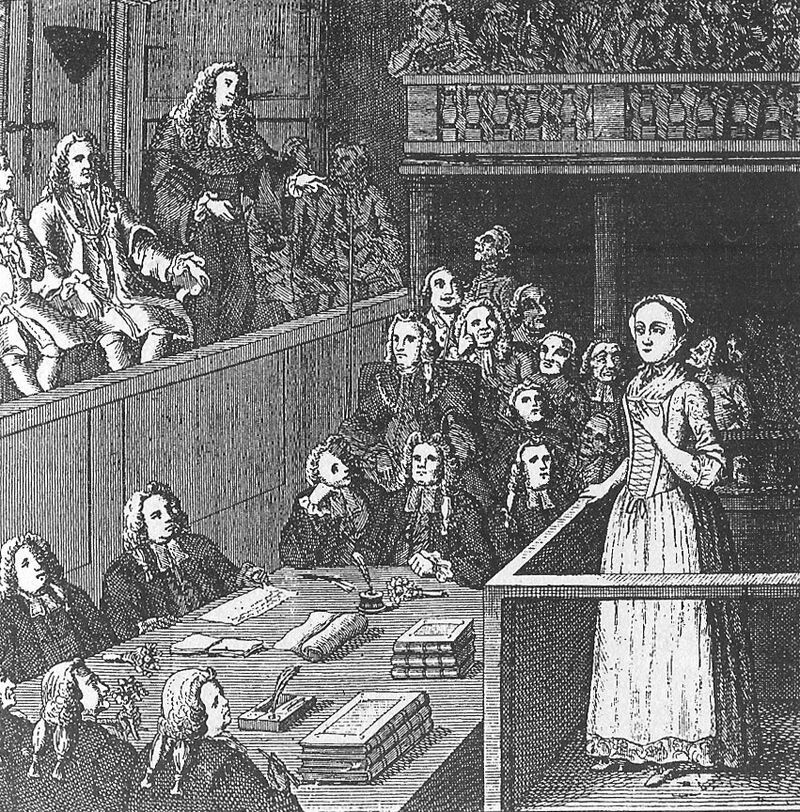

Elizabeth's trial

Although the trial seemed to be going against her, Canning had her supporters. Every day during the hearing a crowd gathered around the courthouse. The peaceful crowd turned violent when the prosecution began throwing stones at Canning's supporters. The crowd dispersed further when the jury found Canning guilty. As punishment, the woman was deported to America. There she quietly married, gave birth to two children and died in 1773.

Thus, from a legal perspective, Canning was not kidnapped. But no further statements were made to clarify the question of what actually happened to her in January 1753. Canning did nothing to clear up this mystery when she stated:

I told the whole truth and nothing but the truth in court; and I'm not going to answer any questions unless it happens again in court.

Unanswered Questions

There is no evidence that Canning had previously engaged in deception, and no accounts of her life in the States indicate that she was prone to making up stories.

Modern lovers of unsolved crimes continue to puzzle over this mystery, but no one has been able to prove what exactly happened to young Elizabeth Canning during her month-long absence.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: