Researchers of the Voynich manuscript are confident that they have unraveled its purpose (10 photos)

The Voynich manuscript has puzzled cryptographers and historians for 600 years. Encrypted text, strange drawings - are these magic spells? Or maybe something obscene? Researchers from Macquarie University came to a different conclusion: the text contains absolutely decent information. But at the beginning of the 15th century, not everyone was allowed to read this.

The study's lead author, Dr. Keegan Brewer, says the manuscript contains information about sex, contraception and the treatment of gynecological diseases, making it a medieval reference book on gynecology.

However, the text of this medical reference book was encrypted in order to limit access to “dangerous” information to a certain circle of readers - namely, women. This is censorship based on gender.

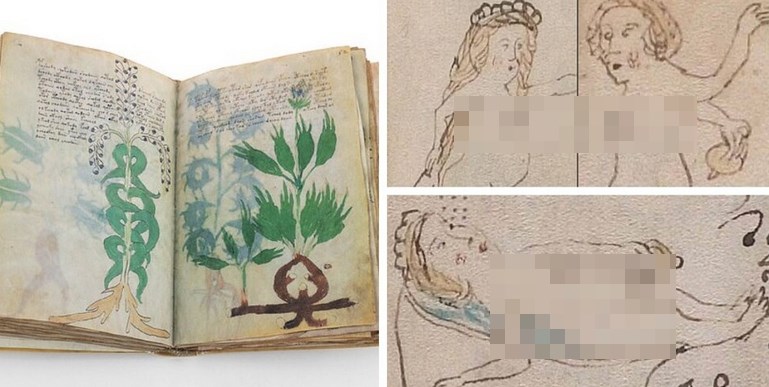

The manuscript contains many illustrations depicting plants, animals or people, but there are those that attracted special attention from researchers. In them we see naked women holding various objects near their genitals or directly pointing at them.

According to the researchers, these drawings are a clear sign that the manuscript contains information about gynecology and sexual health.

“I can't see how it could be about anything else, given that there are plants (which means it's a medical manuscript) and women pointing objects at their vaginas,” Brewer says. “Many commentators on the manuscript ignore this last fact, but it is there.”

“Women's secrets,” as women's health was called in the 15th century, were the subject of close study and written works by medieval authors. And although many medical works on gynecology and obstetrics have survived to this day, many of them were also subject to strict censorship.

“The patriarchal culture of late medieval Europe included a multifaceted male fear of the female body and its natural processes, and this was closely intertwined with medical culture,” explains Brewer.

One 15th-century physician, Johann Hartlieb, even recommended that doctors use a "secret letter" to hide information that could lead to contraception or abortion. He feared that literate women, who were gradually becoming more and more numerous, would be able to read his works and use them for premarital sex.

In the encoded texts of other manuscripts, which have now been deciphered, various recipes and formulas for gynecological purposes have been discovered.

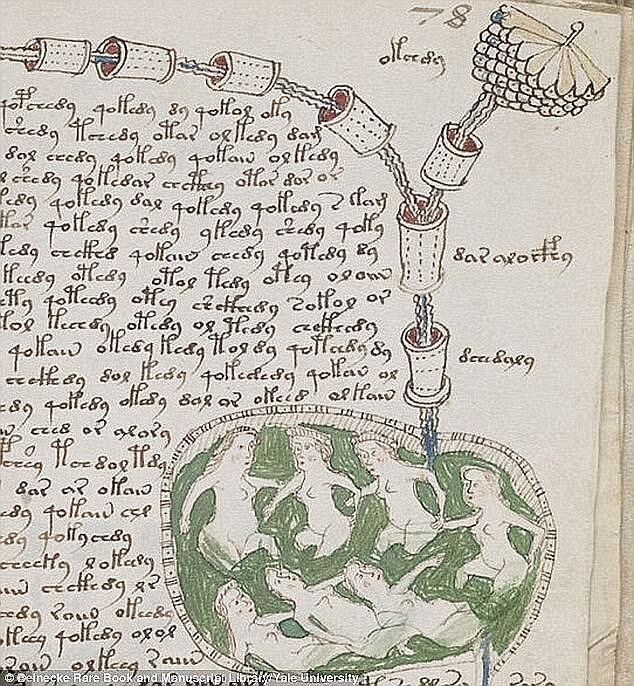

If you think of the Voynich manuscript as a coded gynecological reference book, you can begin to understand the meaning of some of its bizarre illustrations.

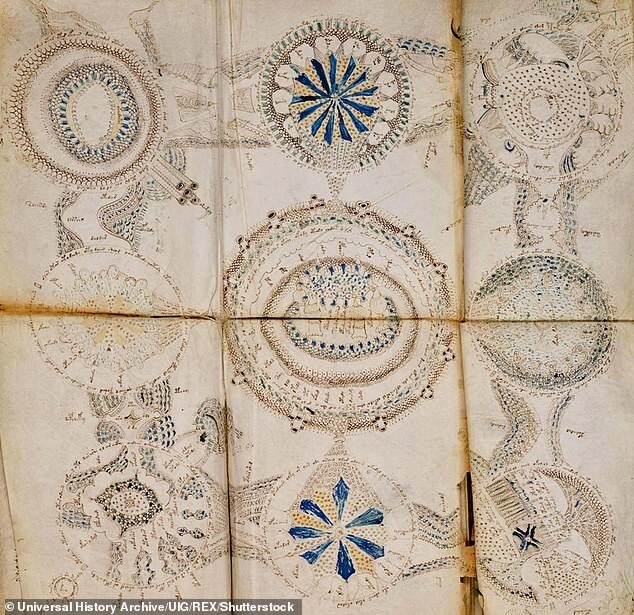

Diagram "Sockets"

The largest and most complex illustration, known as the Rosettes, may actually represent the general understanding of sex and contraception in the late Middle Ages. Then doctors believed that the uterus consisted of seven chambers, and the vagina had two openings - internal and external. It looks like the nine circles in the illustration are exactly that.

“The outer eight circles have smooth edges because they represent internal anatomy, and the center circle has a shaped edge because they represent external anatomy,” says Brewer.

If you follow this logic, other strange details also make sense. For example, in the upper left circle, the five lines going towards the center may represent the five veins that were believed to be present in the vagina of virgins in the Middle Ages.

And the spikes in the upper and lower right circles are the “horns” that were believed to be on the uterus.

“Castles and city walls may be a pun on the German term schloss, which had meanings such as castle, castle, female genitalia and female pelvis,” Brewer adds.

And the two suns in the upper left and lower right likely reflect Aristotle's belief that the sun provided natural warmth to the embryo during its early development.

Even stranger, medieval doctors believed that women received sexual pleasure from “the movement of two sperm in the uterus.” Dr. Brewer and his co-author suggest that the lines and patterns covering the rosettes represent this movement.

While the researchers acknowledge that many of the manuscript's other illustrations require further explanation, this is not the first time that scholars have offered an interpretation related to sexual health.

In 2017, Nicholas Gibbs, an expert on medieval medical manuscripts, already suggested that the text of the Voynich manuscript represents a guide to the health and treatment of gynecological diseases for a “well-to-do” lady.

He came to this conclusion after discovering that the text was written in Latin ligatures, which describe drugs from standard medical reference books. Latin ligatures were developed as short abbreviations and have been used since Greek and Roman times.

For example, the usual ampersand (&) is formed from a ligature when the Latin letters e and t are joined (written "et", which means "and").

Gibbs discovered that each character in the Voynich manuscript was an abbreviation of a word rather than a letter. And also - that in other medieval medical documents and in the Voynich manuscript the same “dominant words” are found, that is, many abbreviations were borrowed from other medical treatises.

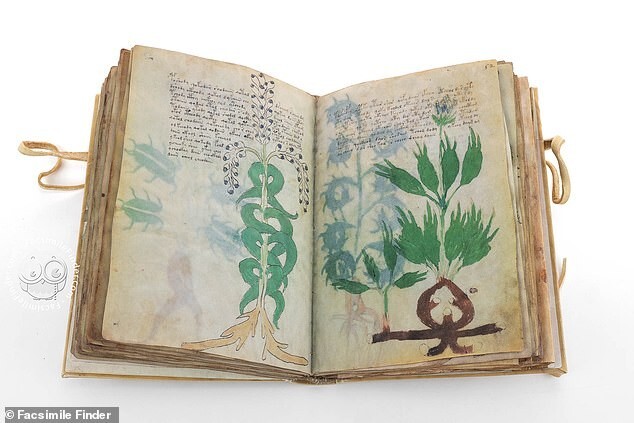

Images of naked women and medicinal plants led him to believe that the text was about aromatherapy, which was practiced by the Greek healer Hippocrates and the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder. According to Gibbs, the illustrations of herbal medicines, zodiac tables and instructions for taking thermal baths indicate that whoever wrote the document was well versed in medieval medicine.

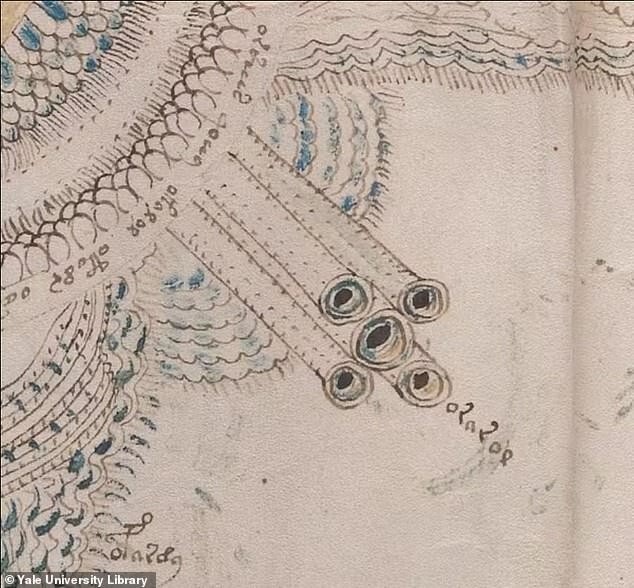

Bathing was practiced by the Greeks and Romans throughout the Middle Ages as a means of healing and treatment. To treat gynecological and other female diseases, “taking water” was often used, either in the form of a bath or orally. Gibbs noticed cylindrical stoves—medieval cooking stoves with upside-down boiling vessels that were used to prepare infusions. This image matched the image of the furnace in a manual written by the surgeon and botanist Hieronius Brunschwig (1450-1512).

***

Although the manuscript has attracted the attention of researchers for hundreds of years, its origins are still shrouded in mystery.

Carbon dating gives a 95 percent chance that the animals whose skins were used to make the pages died between 1404 and 1438. However, the first known owner of the text, an associate of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, was born only 100 years later, in 1552. This makes it difficult to determine for whom the manuscript was written and why, but Dr. Brewer suggests that it was most likely written for a member of an aristocratic family living somewhere in the European Alps region.

Experts believe that this is the work of five different scribes. In 2019, Dr Gerard Cheshire from the University of Bristol said he had translated parts of the text, tracing its connection to the ancient "Proto-Romance" language. The university ultimately refused to support Cheshire after his work was heavily criticized by other scientists.

Given the countless failures, some researchers have even suggested that the manuscript may be nonsense or an elaborate hoax. However, Dr. Brewer remains optimistic that the text will one day be translated.