Armor and Weapons of Ancient Rus' (28 photos)

Russian soldiers were skilled in using these weapons and, under the command of brave military leaders, more than once won victories over the enemy.

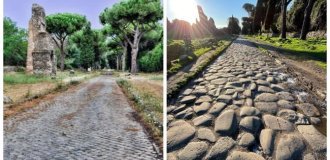

For 800 years, the Slavic tribes, in the struggle with numerous peoples of Europe and Asia and with the powerful Roman Empire - Western and Eastern, and then with the Khazar Khaganate and the Franks, defended their independence and united. In this centuries-old struggle, the military organization of the Slavs took shape, their military art arose and developed, which influenced the state of the troops of neighboring peoples and states. Emperor Mauritius, for example, recommended that the Byzantine army widely use the methods of warfare used by the Slavs...

The flail is a short belt whip with an iron ball suspended at the end. Sometimes spikes were also attached to the ball. They dealt terrible blows with flails. With minimal effort, the effect was stunning. By the way, the word “stun” used to mean “to hit the enemy’s skull hard.”

The head of the shestoper consisted of metal plates - “feathers” (hence its name). The shestoper, widespread mainly in the 15th-17th centuries, could serve as a sign of the power of military leaders, while remaining at the same time a serious weapon.

Both the mace and the shestoper originate from the club - a massive club with a thickened end, usually bound in iron or studded with large iron nails - which was also in service with Russian soldiers for a long time.

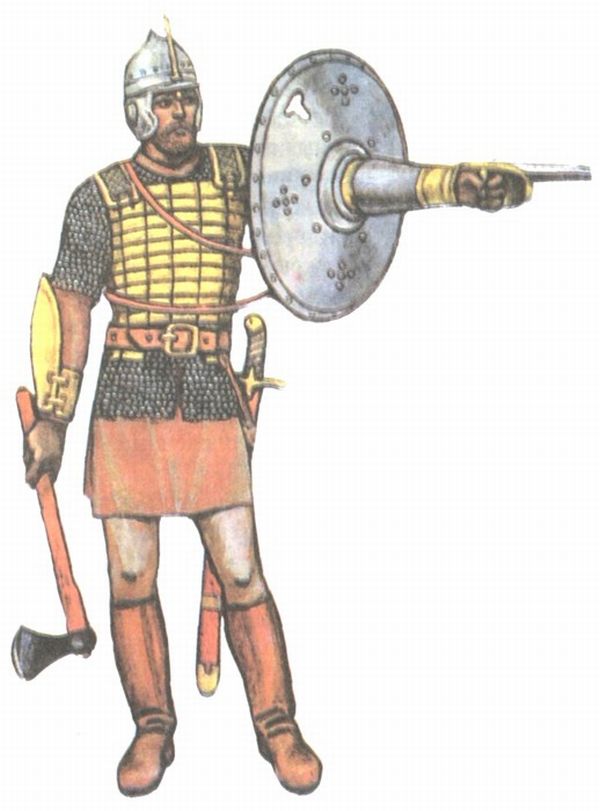

A very common chopping weapon in the ancient Russian army was the ax, which was used by princes, princely warriors, and militias, both on foot and on horseback. However, there was a difference: those on foot more often used large axes, while those on horseback used axes, that is, short axes. For both of them, the ax was put on a wooden ax handle with a metal tip. The back flat part of the ax was called the butt, and the hatchet was called the butt. The blades of the axes were trapezoidal in shape.

The large wide ax was called a berdysh. Its blade, made of iron, was long and mounted on a long axe, which had an iron frame, or thread, at the lower end. Berdysh were used only by infantrymen. In the 16th century, berdysh were widely used in the Streltsy army.

Later, halberds appeared in the Russian army - modified axes of various shapes, ending in a spear. The blade was mounted on a long shaft (axe) and was often decorated with gilding or embossing.

A type of metal hammer, pointed at the butt side, was called a mint or klevets. The coin was mounted on an ax with a tip. There were coins with an unscrewing, hidden dagger. The coin served not only as a weapon, it was a distinctive accessory of military leaders.

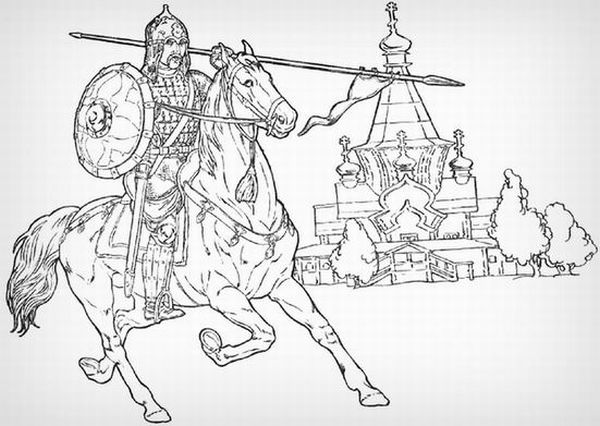

Piercing weapons - spears and spears - were no less important than the sword as part of the armament of the ancient Russian troops. Spears and spears often decided the success of a battle, as was the case in the battle of 1378 on the Vozha River in the Ryazan land, where Moscow cavalry regiments, with a simultaneous blow “on spears” from three sides, overturned the Mongol army and defeated it. The spear tips were perfectly suited for piercing armor. To do this, they were made narrow, massive and elongated, usually tetrahedral.

The tips, diamond-shaped, laurel-leaved or wide wedge-shaped, could be used against the enemy in places not protected by armor. A two-meter spear with such a tip inflicted dangerous lacerations and caused the rapid death of the enemy or his horse.

The spear consisted of a shaft and a blade with a special sleeve, which was mounted on the shaft. In Ancient Rus', shafts were called oskepische (hunting) or ratovishche (battle). They were made from oak, birch or maple, sometimes using metal. The blade (the tip of the spear) was called a feather, and its sleeve was called a vtok. It was often all-steel, but welding technologies from iron and steel strips, as well as all-iron ones, were also used.

The rods had a tip in the form of a bay leaf, 5-6.5 centimeters wide and up to 60 centimeters long. To make it easier for a warrior to hold a weapon, two or three metal knots were attached to the shaft of the spear.

A type of spear was the sovnya (owl), which had a curved stripe with one blade, slightly curved at the end, which was mounted on a long shaft.

The first Novgorod chronicle records how the defeated army “... ran into the forest, throwing away weapons, shields, owls, and everything from themselves.”

[img]https://cn1.nevsedoma.com.ua/images/2011/37/7/dospehi7.jp

g[/img]

Sulitsa was a throwing spear with a light and thin shaft up to 1.5 meters long. The tips of the sulits are petiolate and socketed.

Old Russian warriors defended themselves from bladed and thrown weapons with the help of shields. Even the words “shield” and “protection” have the same root. Shields have been used since ancient times until the spread of firearms. At first, shields served as the only means of protection in battle; chain mail and helmets appeared later. The earliest written evidence of Slavic shields was found in Byzantine manuscripts of the 6th century.

According to the definition of the degenerate Romans: “Each man is armed with two small spears, and some of them with shields, strong, but difficult to carry.”

An original feature of the design of heavy shields of this period was the embrasures sometimes made in their upper part - windows for viewing. In the early Middle Ages, militiamen often did not have helmets, so they preferred to hide behind a shield “with their heads.”

According to legends, berserkers gnawed their shields in a battle frenzy. Reports of this custom of theirs are most likely fiction. But it is not difficult to guess what exactly formed its basis.

In the Middle Ages, strong warriors preferred not to bind their shield with iron on top. The ax would still not break from hitting the steel strip, but it could get stuck in the tree. It is clear that the axe-catcher shield had to be very durable and heavy. And its top edge looked “gnawed”.

Another original aspect of the relationship between berserkers and their shields was that the “warriors in bearskins” often had no other weapons. The berserker could fight with only one shield, striking with its edges or simply throwing enemies to the ground. This style of fighting was known back in Rome.

The earliest finds of shield elements date back to the 10th century. Of course, only metal parts were preserved - umbons (an iron hemisphere in the center of the shield, which served to repel a blow) and fittings (fasteners along the edge of the shield) - but from them it was possible to restore the appearance of the shield as a whole. According to reconstructions by archaeologists, the shields of the 8th - 10th centuries had a round shape. Later, almond-shaped shields appeared, and from the 13th century, triangular-shaped shields were also known.

The Old Russian round shield is of Scandinavian origin. This makes it possible to use materials from Scandinavian burial grounds, for example, the Swedish Birka burial ground, to reconstruct the Old Russian shield. Only there the remains of 68 shields were found. They had a round shape and a diameter of up to 95 cm. In three samples it was possible to determine the type of wood of the shield field - maple, fir and yew.

The species for some wooden handles was also established - juniper, alder, poplar. In some cases, metal handles made of iron with bronze overlays were found. A similar overlay was found on our territory - in Staraya Ladoga, and is now kept in a private collection. Also, among the remains of both Old Russian and Scandinavian shields, rings and brackets for belt fastening the shield on the shoulder were found.

Helmets (or helmets) are a type of combat headgear. In Rus', the first helmets appeared in the 9th – 10th centuries. At this time, they became widespread in Western Asia and Kievan Rus, but were rare in Western Europe. The helmets that appeared later in Western Europe were lower and tailored to the head, in contrast to the conical helmets of ancient Russian warriors. By the way, the conical shape gave great advantages, since the high conical tip prevented a direct blow, which is important in areas of horse-saber combat.

Helmet "Norman type"

Helmets found in burials of the 9th – 10th centuries. have several types. Thus, one of the helmets from the Gnezdovo burial mounds (Smolensk region) was hemispherical in shape, tied along the sides and along the ridge (from the forehead to the back of the head) with iron strips. Another helmet from the same burials had a typically Asian shape - made of four riveted triangular parts. The seams were covered with iron strips. A pommel and lower rim were present.

The conical shape of the helmet came to us from Asia and is called the “Norman type”. But she was soon supplanted by the “Chernigov type.” It is more spherical - it has a spheroconic shape. On top there are pommels with bushings for plumes. In the middle they are reinforced with spiked linings.

Helmet "Chernigov type"

According to ancient Russian concepts, the combat attire itself, without a helmet, was called armor; later this word came to refer to all the protective equipment of a warrior. For a long time, chain mail belonged to the indisputable pe

zeal. It was used throughout the X-XVII centuries.

In addition to chain mail, protective clothing made of plates was adopted in Rus', but did not prevail until the 13th century. Lamellar armor existed in Rus' from the 9th to the 15th centuries, and scale armor - from the 11th to the 17th centuries. The latter type of armor was particularly elastic. In the 13th century, a number of items enhancing body protection, such as leggings, knee pads, breast plates (Mirror), and handcuffs, became widespread.

To strengthen the chain mail or shell in the 16th-17th centuries in Russia, additional armor was used, which was worn over the armor. These armors were called mirrors. They consisted in most cases of four large plates - front, back and two side ones. The plates, whose weight rarely exceeded 2 kilograms, were connected to each other and fastened on the shoulders and sides with belts with buckles (shoulder pads and amices).

A mirror, polished and polished to a mirror shine (hence the name of the armor), often covered with gilding, decorated with engraving and chasing, in the 17th century most often had a purely decorative character.

In the 16th century in Rus', ringed armor and breast armor made of rings and plates connected together, arranged like fish scales, became widespread. Such armor was called bakhterets. Bakhterets was assembled from oblong plates arranged in vertical rows, connected by rings on the short sides. The side and shoulder slits were connected using straps and buckles. A chain mail hem was added to the bakhterts, and sometimes collars and sleeves were added.

The average weight of such armor reached 10-12 kilograms. At the same time, the shield, having lost its combat significance, becomes a ceremonial item. This also applied to the tarch - a shield, the top of which was a metal hand with a blade. Such a shield was used in the defense of fortresses, but was extremely rare.

Bakhterets and shield-tarch with a metal “arm”

In the 9th-10th centuries, helmets were made from several metal plates connected to each other with rivets. After assembly, the helmet was decorated with silver, gold and iron plates with ornaments, inscriptions or images. In those days, a smoothly curved, elongated helmet with a rod at the top was common. Western Europe did not know helmets of this form at all, but they were widespread both in Western Asia and in Rus'.

In the 11th-13th centuries, domed and spheroconic helmets were common in Rus'. At the top, helmets often ended with a sleeve, which was sometimes equipped with a flag - a yalovets. In early times, helmets were made from several (two or four) parts riveted together. There were helmets made from one piece of metal.

The need to enhance the protective properties of the helmet led to the appearance of steep-sided dome-shaped helmets with a nose or a face mask (visor). The warrior's neck was covered with a net-barmitsa, made of the same rings as the chain mail. It was attached to the helmet from the back and sides. The helmets of noble warriors were trimmed with silver, and sometimes were entirely gilded.

The earliest appearance in Rus' of headgear with a circular chainmail aventail hung from the crown of the helmet, and a steel half-mask laced in front to the lower edge, can be assumed no later than the 10th century.

At the end of the 12th - beginning of the 13th century, in connection with the pan-European tendency to make defensive armor heavier, helmets appeared in Rus', equipped with a mask-mask that protected the warrior’s face from both chopping and piercing blows. Face masks were equipped with slits for the eyes and nasal openings and covered the face either half (half mask) or entirely.

The helmet with the mask was put on a balaclava and worn with the aventail. Face masks, in addition to their direct purpose - to protect the warrior’s face, were also supposed to intimidate the enemy with their appearance. Instead of a straight sword, a saber appeared - a curved sword. The saber is very convenient for the conning tower. In skillful hands, the saber is a terrible weapon.

Around 1380, firearms appeared in Rus'. However, traditional melee and ranged weapons have retained their importance. Pikes, spears, maces, flails, pole-toppers, helmets, armor, round shields were in service for 200 years with virtually no significant changes, and even with the advent of firearms.

From the 12th century, the weapons of both horsemen and infantry gradually became heavier. A massive long saber appears, a heavy sword with a long crosshair and sometimes a one-and-a-half hilt. The strengthening of defensive weapons is evidenced by the technique of ramming with a spear, which became widespread in the 12th century. Weighting the equipment would not

It was significant, because it would make the Russian warrior clumsy and turn him into a sure target for the steppe nomad.

The number of troops of the Old Russian state reached a significant figure. According to the chronicler Leo the Deacon, an army of 88 thousand people took part in Oleg’s campaign against Byzantium; in the campaign to Bulgaria, Svyatoslav had 60 thousand people. Sources name the voivode and the thousand as the commanding staff of the Russian army. The army had a certain organization associated with the organization of Russian cities.

The city exhibited a “thousand”, divided into hundreds and tens (by “ends” and streets). The “thousand” was commanded by the tysyatsky, who was elected by the veche; subsequently, the tysyatsky was appointed by the prince. The “hundreds” and “tens” were commanded by elected sotskys and tens. Cities fielded infantry, which at that time was the main branch of the army and was divided into archers and spearmen. The core of the army was the princely squads.

In the 10th century, the term “regiment” was first used as the name of a separately operating army. In the “Tale of Bygone Years” for 1093, regiments are called military detachments brought to the battlefield by individual princes.

The numerical composition of the regiment was not determined, or, in other words, the regiment was not a specific unit of organizational division, although in battle, when placing troops in battle formation, the division of troops into regiments was important.

A system of penalties and rewards was gradually developed. According to later data, gold hryvnias (neck hoops) were awarded for military distinctions and services.

Gold hryvnia and gold plates covering a wooden bowl with the image of a fish