Nowadays, few people are interested in historical weapons and history in general. We all watch historical films, see these very swords and armor, but there is often little that is truly historical. Let's find out what kind of swords were in Rus'.

The armament of the army during the time of the first Kyiv princes can be judged mainly by the largest ancient Russian necropolises, where both ordinary soldiers and representatives of the nobility were buried according to the pagan rite of cremation (exceptions are insignificant). The concentration of finds coincides mainly with the largest urban centers (Kyiv, Chernigov, Gnezdovo-Smolensk, Timirevo-Yaroslavl), camps of warriors (Shestovitsy, Chernigov region), areas of active agricultural and trading activities (southeastern Priladozhye, Suzdal Opolye). Many burial mounds of the 10th century provide weapons of professional warriors-warriors, who formed the basis of the ruling class. In these burials (547 of them have been recorded), weapons are not an ethnic, but a social indicator. Accurate calculations of archaeological complexes containing weapons have made it possible to state a relatively high degree of militarization of society in the 10th century, in which every fifth to tenth man carried weapons, as well as significant technical equipment of the army, in which one in three warriors had two or three types of weapons.

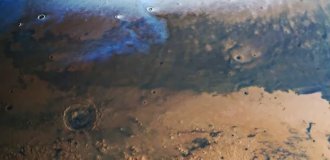

Swords. Typical forms: 1-17 — 9th — 11th centuries; 18-25 — 11th — 14th centuries. 1 — Bor, southeastern Priladozhye; 2 — Gnezdovo, Smolensk region; 3 — Pirkinskoye, southeastern Priladozhye; 4, 5 — Dnieper rapids (Khortitsa Island); 6 — Vakhrusheva, southeastern Priladozhye; 7 — Gnezdovo, Smolensk region; 8 — Shestovitsy, Chernihiv region; 9 — Ruchi, southeastern Priladozhye; 10 — Shestovitsy, Chernihiv region; 11 — Mikhailovskoye, Yaroslavl region; 12 — Gorka Nikolskaya, southeastern Priladozhye; 13 — Leningrad region; 14 — Chernaya Mogila, Chernikov; 15 — Foshchevataya, Poltava region; 16 — Karabichev, Khmelnytsky region; 17 — Krasnyanka, Kharkov region, 18 — Poltava region; 19 — Vozdvizhenskoye, Kostroma region; 20 — Maly, Pskov region; 21 — Kiev; 22 — Kiev, 23 — Kyiv; 24 — Gorodishche, Khmelnytsky region; 25 — Raiki, Zhitomir region.

In comparison with the 10th century. the degree of militarization of society by the 11th century decreased by 2-3 times, which is apparently associated with social changes in the composition of the army and the formation of a closed military class. For the period of the 11th-12th centuries, most of the finds are associated with numerous peasant cemeteries in the forest and forest-steppe zone of Russia (614 burials were recorded). Here, next to the burial mounds of smerds, relatively large and rich burials of junior warriors rose up. In connection with Christianization, the burials of wealthy warriors disappear, but burials of men with weapons (according to the rite of burial) remain. Archaeological data for this period mainly characterize the weapons of an ordinary warrior and a common man, a smerd and a townsman.

During the period of feudal fragmentation that followed, when the army consisted of detachments of individual princes, boyars and regional militias, the number of material sources decreases. Archaeology does not provide a comprehensive picture of the weapons of the various social strata of the population of this period. Burials of the 12th-13th centuries (144 of them have been recorded) characterize the combat equipment of the population living in some border regions of Rus', for example, the Turkic-speaking Black Klobuks (Kiev region) and the Vot militia (Leningrad region). The weapons of the townspeople who died defending Russian cities during the Mongol-Tatar invasion of 1237-1240 are also known. It allows us to imagine a foot warrior with a spear, axe, bow and arrows, and a mounted warrior with stabbing, cutting and defensive weapons.

After 1250, finds of weapons become increasingly rare, but there are works of military craftsmanship that were preserved in princely and city arsenals.

Swords of the 10th — first half of the 11th century. 1 — Foshchevataya, Poltava region (Scandinavian type); 2, 3 — Kyiv and Karabichev, Khmelnytsky region (both — local type A); 4 — Ust Rybezhna, southeastern Priladozhye (type E); 5 — Gnezdovo, Smolensk region (type D); 6 — Glukhovtsy, Zhitomir region (local type A)

Despite the unevenness and sometimes fragmentary nature of the archaeological material, it allows us to study not only the weapons of individual parts of the Russian army (for example, the nomads who settled in the south of the Kiev region), but also the combat equipment of the Russian army as a whole. Thus, based on the collected materials, it was possible to establish the division of the Russian army of the 11th-13th centuries by type and kind of weapon and reconstruct the equipment: heavily armed horsemen and infantrymen - spearmen and lightly armed horsemen and infantrymen - archers.

Swords were a privileged but widespread weapon. Within the 9th-14th centuries, they are divided into two main groups - Carolingian and Romanesque. The first, of which more than 100 have been found, date back to the end of the 9th - first half of the 11th century. Finds of these blades are concentrated in several regions of Rus': in the south-eastern Priladozhye, the areas of Smolensk, Yaroslavl, Novgorod, Kyiv and Chernigov. Swords were found, as a rule, in the largest burial mounds near or on the territory of the most important urban centers. Judging by the wealth of the burials, the blades belonged to warriors-rescuers, merchants, princely-boyar elite, and sometimes wealthy artisans. The rarity of swords in burials (as well as helmets, armor, shields) does not mean their shortage in combat practice, but is explained by other reasons. The sword, as a particularly revered and valuable weapon during the period of early feudalism, was passed down from father to son, and if there was an heir, it was excluded from the number of burial offerings. In a later period, swords were often issued to ordinary warriors from state arsenals, probably only for lifelong possession

A sword is a chopping and chopping-stabbing double-edged melee weapon. Until about the 13th century, the tip was not sharpened. This was due to the fact that the sword was used mainly for chopping blows. The first stabbing blow is mentioned in the chronicle under the year 1255

Swords of the 9th - 11th centuries. 1 - Novgorod (type X); 2 — Ruchi, southeastern Priladozhye (type V — special); 3 — Ust Rybezhna, ibid. (type E); 4 — Gnezdovo, Smolensk region (type V); 5 — Gnezdovo, ibid. (type E); 6 — Leningrad region (type H); 7 — Vakhrusheva, southeastern Priladozhye (type T — 2); 8 — Bor, ibid. (type B); 9 — Zaozerye, ibid. (type T — 2)

Swords begin to appear in the burials of ancient Slavs from the end of the 9th century, but this does not mean that it was during this period that our ancestors first became acquainted with this weapon. Probably, during this period, the final identification of the sword with the owner occurs, and the weapon is sent with him to the other world in order to continue to protect the owner even after death. At the dawn of the development of the blacksmith's craft, when the method of cold forging, which was ineffective compared to the usual one, became widespread, the sword was simply a treasure, truly priceless, no one even thought of burying it, this also explains the rarity of archaeological finds of swords.

Modern scientists divide Slavic swords of the 9th-11th centuries into two dozen types, which, however, differ mainly in the shape of the cross and handle. The blades of these swords are almost the same - 90-100 cm long, 5-7 cm wide at the handle, and tapering towards the end. In the middle of the blade there was a fuller, sometimes incorrectly called a "blood drain". At first, the fuller was quite wide, but over time it narrowed, and then completely disappeared. The true purpose of the fuller is to reduce the weight of the blade, and not at all to drain blood, because, as already mentioned, stabbing blows with a sword were extremely rare until the 13th century.

Sword hilts (1-2), sabers, their scabbards (3-4), 10th-12th centuries. 1 - Mali, Pskov region, 12th century; 2 - Mikhailovskoye, Yaroslavl region, 10th century; 3 - hilt of "Charlemagne's saber", 950-1025; 4 - scabbard lining of the same saber.

The blade thickness in the fuller area was about 2.5 millimeters, and on the sides - 6 mm. However, due to the special metal finishing, such a difference in thickness did not affect the strength of the blade. The weight of such a sword was on average one and a half kilograms.

Not every warrior had a sword. Firstly, they were very expensive because the process of producing a good sword was long and complicated. Secondly, a sword is a professional weapon, requiring remarkable physical strength and dexterity in wielding this noble weapon.

How did our ancestors make swords that were deservedly respected in the countries where they were exported?

When it comes to high-quality melee weapons, the famous damask steel immediately comes to mind. Damask steel is a special type of steel with a carbon content of more than 1 percent and with its uneven distribution in the metal. A sword made of such steel had truly mutually exclusive properties - for example, a damask blade was able to cut iron and even steel, while it did not break when bent into a ring. It was good in all respects, but… it could not withstand the severe northern frosts, so it was practically unsuitable for the Russian climate. How did the Slavs get out of this situation?

To obtain a metal with an uneven carbon content, Slavic blacksmiths took rods or strips of iron and steel, folded or twisted them together through one and then forged them many times, folded them again several times, twisted them, assembled them like an accordion, cut them lengthwise, forged them again, and so on. The result was strips of beautiful and very strong patterned steel, which was etched to reveal the characteristic herringbone pattern. It was this steel that allowed swords to be made thin enough without losing strength, and it was thanks to it that the blades straightened out when bent in half.

Often, strips of welded damask steel ("Damascus") formed the basis of the blade, and high-carbon steel blades were welded along the edge: it was pre-subjected to the so-called cementation - heating in the presence of carbon, which impregnated the metal, giving it special hardness. Such a sword was quite capable of cutting through the armor and chain mail of the enemy, because they were usually made of steel or iron of lower grades. They also cut through the blades of swords made less carefully.

Experts emphasize that welding iron and steel - alloys that differ significantly in melting point - is a process that requires the highest skill from the blacksmith. And archaeological data confirm that in the 9th-11th centuries our ancestors were quite skilled in this craft, and not just “able to make simple iron objects”!

In this regard, it is worth telling the story of a sword found in the town of Foshchevataya, in the Poltava region of Ukraine. It was long considered “undoubtedly Scandinavian”, since the handle has patterns in the form of intertwined monsters, very similar to the ornament of the memorial stones of Scandinavia in the 11th century. True, Scandinavian scientists paid attention to some features of the style and suggested looking for the birthplace of the sword in the South-Eastern Baltic. But when the blade was finally treated with a special chemical composition, clear Cyrillic letters suddenly appeared on it: “LUDOTA KOVAL”. A sensation broke out in science: the “undoubtedly Scandinavian” sword turned out to be made here, in Rus'!

To avoid being deceived, the buyer first checked the sword by its ringing: a good sword would make a clear and long sound from a light click on the blade. The higher and clearer it was, the better the damask steel. They also tested its elasticity: would it remain curved after it was placed on your head and bent (to your ears) by both ends. Finally, the sword had to easily (without becoming dull) cut a thick nail and cut the thinnest fabric thrown on the blade.

Good swords were usually richly decorated. Some warriors inserted precious stones into the handle of the sword, as if in gratitude for the fact that the sword did not let its owner down in battle. Such swords were truly worth their weight in gold.

Later, swords, like other weapons, changed significantly. Maintaining the continuity of development, at the end of the 11th - beginning of the 12th century, swords became shorter (up to 86 cm), lighter (up to 1 kg) and thinner, their fuller, which occupied half the width of the blade in the 9th-10th centuries, in the 11th-12th centuries occupied only a third, to turn into a narrow groove in the 13th century. In the 12th-13th centuries, as military armor became stronger, the blade again stretched in length (up to 120 cm) and became heavier (up to 2 kg). The handle also became longer: this is how two-handed swords came into being. Swords of the 12th-13th centuries were still mostly used for chopping, but they could also be used for stabbing. Around the 12th - 13th centuries, another type of sword emerged: the so-called two-handed sword. Its weight is approximately 2 kg, the length increases to 120 cm. The fuller completely disappears, since the emphasis is again placed on the mass, the technique of working with the sword undergoes significant changes; at the same time, the tip acquires its original piercing properties, which is associated with the appearance of composite armor.

The sword was worn in a scabbard, usually wooden, covered with leather, either on the belt or behind the back. (Riders practically did not use swords because the center of gravity was shifted to the handle, and this made it difficult to strike from top to bottom, from the saddle). The scabbard had two sides - the mouth and the tip. Near the mouth of the scabbard there was a ring for attaching a sling. However, it also happened that swords were worn simply threaded through two rings, partly out of a desire to show off the blade, partly... simply because of a lack of funds. The scabbard was decorated no less richly than the sword. Sometimes the cost of the weapon was much higher than the cost of the owner's other property. As a rule, a prince's warrior could afford to buy a sword, less often - a wealthy militiaman.

The sword was used in infantry and cavalry up until the 16th century. True, in cavalry it was significantly "crowded out" by the sabre, which was more convenient in equestrian formation. However, the sword, unlike the sabre, always remained a native Russian weapon.

Sources: M. Semenova "We are Slavs!" M. Gorelik "Warriors of Kievan Rus IX-XI centuries"