Interesting and rare retro photographs of Europe (20 photos)

From the street scenes of Paris and Berlin to the drab courtyards of Budapest, from the sunny terraces of Italy to the gray streets of post-war Warsaw, each photograph here tells a story about how people lived in neighboring countries.

Berlin, 1960.

Photographer: Konrad Gier

In the 1960s, women's fashion quickly shifted from the modest post-war silhouettes to daring innovations: miniskirts (influenced by Mary Quant), geometric patterns, bright colors, form-fitting sheath dresses, and pantsuits.

People's Republic of Poland. Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, built by the Soviet Union and donated to the People's Republic of Poland in 1955, 1971.

Photographer: A. Novoselsky

On July 22, 1955, the Palace of Culture and Science, a 42-story skyscraper gifted to the Polish capital by the Soviet Union, was ceremoniously opened in Warsaw. Initially, the building bore the name of I.V. Stalin, but after the 20th Congress of the CPSU and the subsequent de-Stalinization, this name was removed. Until 2022, the building remained one of the tallest buildings not only in Warsaw, but in all of Poland. Architecturally, the Palace is designed in the style of the so-called "Stalinist skyscrapers": monumental, decorated with stucco, a spire, and socialist realist symbols. From 1955 to 1957, it was the tallest building in Europe, and today it ranks among the top ten tallest skyscrapers in the European Union. A gift "from the fraternal Soviet people," it was built from May 2, 1952, to July 22, 1955, by 3,500 Soviet workers and engineers. An entire residential area, complete with a cinema, cafeteria, club, and even a swimming pool, was built specifically for them to provide living and leisure facilities for the construction workers far from their homeland. Although for many Poles, the Palace of Culture and Science remains a controversial symbol of Soviet influence, its scale, historical significance, and role in modern Warsaw life are undeniable.

Turf hut. Netherlands, 1926.

In the Netherlands, such structures were traditionally built in poor rural areas, especially on peat bogs (for example, in the provinces of Drenthe or Friesland), where timber was scarce and stone expensive. Turf walls provided good thermal insulation but required constant maintenance: they were regularly replenished and coated with clay.

Samuel Granovsky at the Café de la Rotonde, Paris, 1930s.

Photographer: Emil Savitri

Khaim Granovsky was born in Yekaterinoslav to a bourgeois Jewish family. In 1901, he entered the Odessa Art School, but was temporarily expelled in the fall of 1904—he was called up for military service during the Russo-Japanese War. After his military service, he did not return to the school. In 1908, he went to Munich to continue his art education, and in 1909, he settled in Paris, where he became part of the vibrant artistic scene of Montparnasse. With the outbreak of World War I, he returned to Odessa, but in 1920 he left for Paris again, settling in the renowned artists' hostel, "La Ruche." There, he became fascinated with Dadaism and became an active participant in the avant-garde movement: he created frescoes, paintings, furniture, and screens, and worked as a set designer, notably designing the designs for Tristan Tzara's legendary play "The Air Heart." When his art income was insufficient, Granovsky worked as a cleaner at the iconic Parisian café Rotonde—a meeting place for artists, poets, and philosophers. Possessing a striking appearance and charisma, he often became a model for other artists. He was remembered for strolling the streets of Paris in a plaid shirt and a Texas hat—this eccentric look earned him the nickname "The Cowboy of Montparnasse." A tragic fate befell him during the Occupation: on July 17, 1942, Chaim Granovsky was arrested during a Nazi roundup in Paris, sent to the Drancy camp, and on July 22, 1942, deported to Auschwitz, where he soon died.

Naples, Italy, 1959.

Photographer: Herbert List

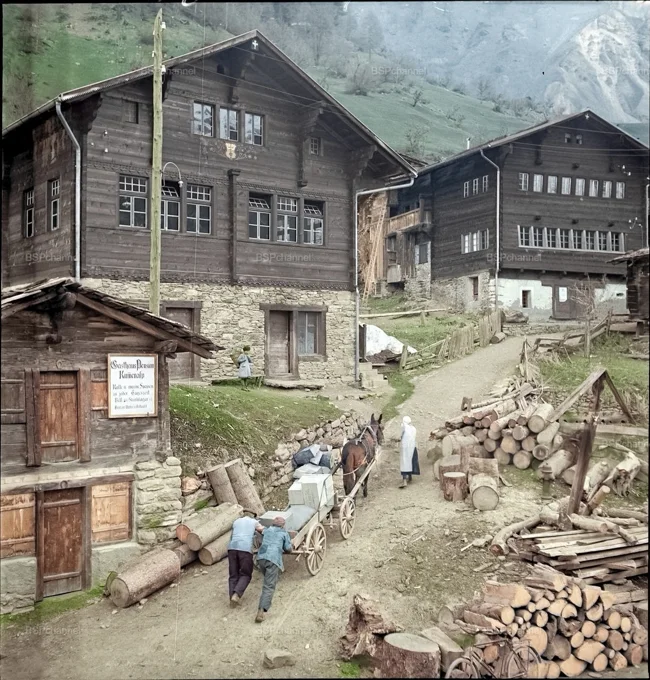

Oberdorf, Switzerland, circa 1943.

Photographer: Leonard von Matt

Sardinia, Italy, 1959.

Dutch schoolboy wearing clogs over a thick wool sock, mid-20th century.

Dutch klompen are traditional wooden footwear that have become one of the most recognizable symbols of the Netherlands. Klompen are handcrafted (or machine-made) from a single piece of wood—most often poplar, alder, or willow, less commonly beech. The wood is chosen for its lightness, softness, and moisture resistance. The inside of the klompen is smoothly hollowed out, and the outside can be decorated with carvings, painting, or coated with a protective varnish. Klompen were originally worn by farmers, fishermen, workers in peat bogs, and dairy farms. They protected their feet from cold, moisture, and dirt, and were also practical: they stayed in place on wet ground, were waterproof, and lasted for years. Furthermore, wood is a good insulator, so klompen were warm in winter and cool in summer. Although klompen are rarely used in everyday life today, they remain part of the national costume, especially during festivals, fairs, and tourist attractions. Many Dutch people still keep a pair of klompen at home—as a tribute to tradition or for gardening. Against the backdrop of these neat wooden klompen, which have become the pride and hallmark of the Netherlands, it's especially offensive to see how bast shoes are still disparaged and ridiculed in our country. In Holland, they've managed to preserve, respect, and transform simple work footwear into a symbol of national identity—they're worn at celebrations, handmade, given to guests, and are a source of pride. In our country, bast shoes are still associated with "poverty," "backwardness," or even "shame"—as if wearing what protected our ancestors' feet from cold and dirt for centuries is shameful. Meanwhile, bast shoes are a fine craft: woven from linden bast, lightweight, breathable, and remarkably durable. They were part of everyday life, culture, even folklore. The difference isn't in the shoes themselves, but in their attitude toward their heritage. One nation has embraced its past as a virtue. Another is still ashamed of it. But that's a shame. Bast shoes aren't a disgrace, but a reminder of hard work, resourcefulness, and a connection to the land. They shouldn't be hidden, but rather cherished, as they do with klompen shoes in Holland.

Budapest, 1966.

Photographer: Rudolf Jaray

Shrimp fishing in France. Early 20th century.

Rome. Colosseum, 1972.

Visit of Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, to France. Marseille, 1960.

Photographer: V. Volodkin

In May 1960, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers, made an official visit to France, which became one of the most striking episodes of Soviet diplomacy during the "thaw." Khrushchev was greeted with great excitement: crowds of onlookers, slogans in French, sailors from Soviet merchant ships docked in the port—all created the atmosphere of a true international event. The visit underscored the USSR's desire for cultural and political dialogue with Europe, demonstrating that behind the "Iron Curtain" lay not only missiles but also a willingness to cooperate. However, even then, the shadow of an impending crisis loomed over the visit: just a few days after Khrushchev's departure from France, the U-2 spy plane scandal erupted, sharply cooling relations between the USSR and the West.

Czechoslovakia, 1959.

Photographer: Karol Kállay

Netherlands, 1956.

Photographer: Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cyclist. France, 1949.

Photographer: Robert Doisneau

Prostitutes buy illegal drugs from an illegal street dealer – a "coke Emil" in the slang of the time. Berlin, May 1929.

Cyclists, Sainte-Maxime, France, 1972.

Photographer: Robert Doisneau

A seal, balancing a doll, entertains children at a performance by the Circus Krone. Aachen, West Germany, 1962.

Transporting cargo by horse-drawn cart. Lötschental, Switzerland, 1941.