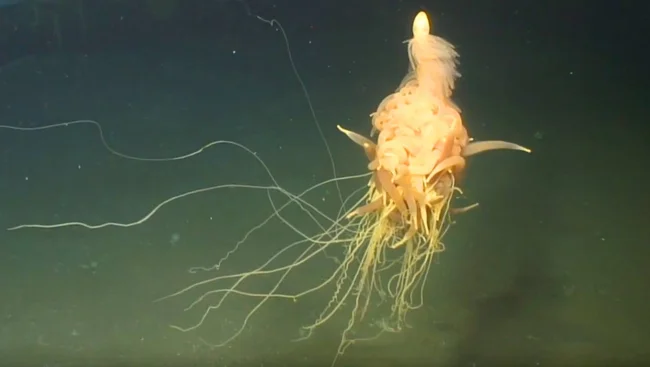

Batifisa Lumpy: The Spaghetti Monster in Real Life (11 photos)

Did you also dream of having several clones as a child? So they could do your homework for you, help mom around the house, while you sat and watched cartoons? What's childhood? I bet even adults would love that! What a dream! But for the Spaghetti Monster, such a scenario is a completely ordinary reality.

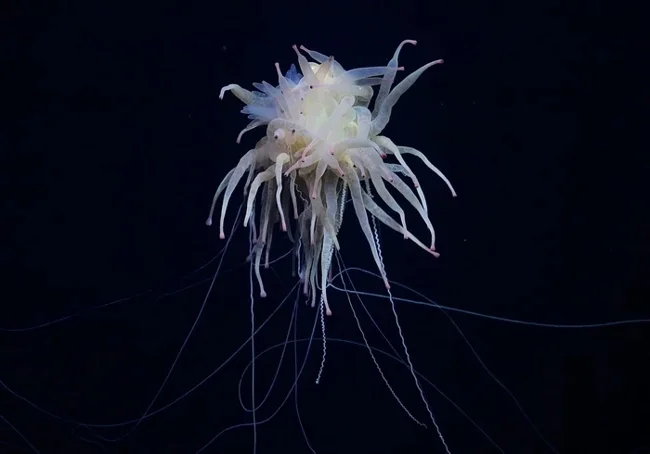

Meet the Bathyphysis lumpis. The internet has dubbed it the "Spaghetti Monster." It's easy to see why—just look at the photo.

Mom told me, don't leave a pot of pasta in the fridge for a month!

A mess of tentacles and strange growths is crumpled into a lump of bio-mess. At first glance, it's hard to figure out what it is. And at second glance, too. And if you look closely, it actually seems like this guy is an alien from another planet.

When you're cleaning out the drain and you pull out THIS.

The Bathyphysa lumbricoides is a member of the order Siphonophora. They are distant relatives of jellyfish. However, unlike them, and almost all other modern animals in general, the Bathyphysa prefers the pronoun "we/us." Because it is one of the most unusual underwater creatures—a single organism, but created from several individual clones, or zooids. A kind of communal colony. Clones can't live separately, outside the colony, but the colony itself is quite capable of creating a ton of clones to replace the others. It sounds complicated, but we'll figure it out now.

The gods didn't die. They moved closer to Cthulhu.

Like all living things, the bathyphysis begins its journey with a single fertilized cell, a zygote. After a week or two, the zygote develops into a free-floating larva. For a while, it drifts with the current and gains strength, after which the biological magic begins. The larva creates an exact copy of itself, then a second, third, fourth... Yes, some coelenterates, such as the hydras studied in school, also reproduce by creating their own clones. But with the bathyphyse, things are different. Hydra clones bud off and break off, beginning their own independent lives. But with the spaghetti monster, all the zooid clones remain together. Moreover, immediately after birth, each clone receives its own "profession."

This is what a truly multifaceted personality looks like.

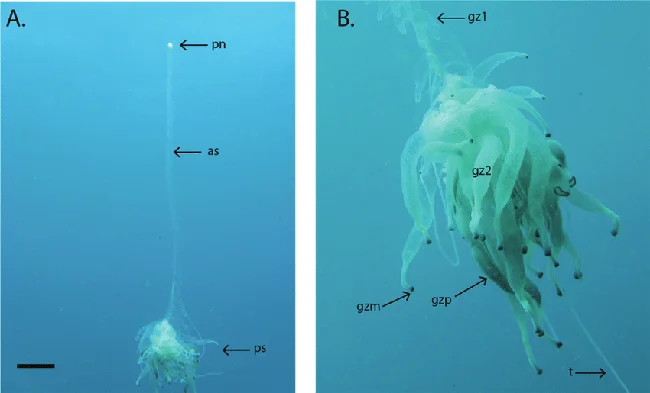

At the very top of the colony is the pneumatophore zooid. It's a gas-filled, cone-shaped bladder. That's all. Even though the pneumatophore is essentially a "separate organism," it still can't exist independently. The pneumatophore has no other organs; it's simply a highly specialized clone with the easiest job. It must maintain the balance of the entire colony and ensure it doesn't tip over. Other zooids provide it with nutrients.

That reddish bump at the top is the pneumatophore.

Several nectophores are located just below it. They look like thick spaghetti and are responsible for the movement of the entire colony. Nectophores contract like an umbrella—opening and closing, capturing and expelling water, which enables propulsion. Of course, such a propulsion doesn't allow for much speed, so bathyphyses can't simply swim away. They spend their entire lives in controlled drift across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Colonies are found only at great depths, from 1,000 to 4,000 meters. It's dark and cold there, and there's nowhere to swim.

My dreams are at 39 degrees.

Dangling from the sides of the bathyphyse are thin, long, spaghetti-like zooids called dactylozooids. These are the main feeders: they contain hundreds of tiny stinging cells, like harpoons containing venom, that react to the slightest movement. Their job is to detect, immobilize, and deliver prey to the center of the colony. Yes, this strange spaghetti monster is a predator! But rather than actively hunting, it prefers to simply dangle a bunch of dactylozooids and wait for something edible to float nearby. Fish, crustaceans, whatever—in the deep sea, you're spoiled for choice.

Give a poor Pastafarian some food!

The captured prey is then taken to the gastrozooid clones. This is the colony's dining hall. Since no clone is capable of digestion, the gastrozooids supply them with nutrients. They digest the food, break it down into nutrients, and distribute them to the other zooids. The most delicious job! At the edge of the colony is the gonozooid clone, which is responsible for the reproduction of the bathyphyse. Moreover, a clone is only of one specific sex and, accordingly, produces either sperm or eggs. As the reproductive products mature, they are simply ejected into the environment without ceremony. Moreover, many bathyphyse living nearby do this almost simultaneously. Apparently, there is a specific trigger for the onset of reproduction—warming water, a change in current, the presence of pheromones, or perhaps all three. Since spaghetti monsters are observed only by oil workers and deep-sea submersibles, this part of the colonial organism's life is still hidden from us.

Batyphysa was first discovered in 2015. It wasn't scientists who discovered it, but oil workers surveying the deep seabed off the coast of Angola.

And yet, since bathyphysa are still alive, it means they reproduce quite successfully. Sex cells meet somewhere in the water column and fuse into a zygote, which will eventually grow into a new colony, and the cycle will repeat itself. And here a logical question arises: Why complicate things so much? Sculpt some clones, invent different tasks for them, distribute the work, coordinate it all? Why not just do it like us—one organism with different organs inside it?

— Marya Ivanovna, I forgot to do my homework. — Did you leave your head at home? — I forgot...

Because siphonophores as a group appeared over 600 million years ago. Back then, there was absolutely nothing on Earth. Just now, some strange algae, coelenterates, hydras, and other very strange, asymmetrical creatures, unfamiliar to us, were floating in the water. Life had only just reached the multicellular level back then and was simply experimenting. For their time, colonial organisms were incredibly advanced, having already developed some sort of specialization of individual body parts and an internal system. It was strange, but still better than nothing at all.

Invented organ division before organs were invented!

And this same strange system has helped siphonophores survive to this day. Countless modern, advanced species with more sophisticated anatomy have gone extinct, but these spaghetti monsters have survived. Because more complex doesn't mean more successful. If a clone of a bathyphyse dies, the colony won't suffer; it will simply grow a new one in its place. But can we, complex humans with a very sophisticated anatomy, grow at least one tooth in place of the old one?