Mehrangarh Fort: memorable marks of a fatal faith on bricks of history (10 photos)

The Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India, has murals that offer a glimpse into the infernal past of Hindu traditions.

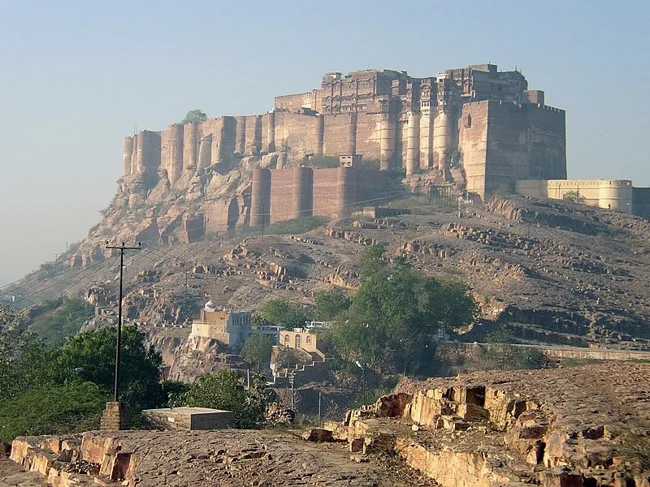

Its handprinted walls and echoing zenanas continue to tell tales of bygone times. One such element is the 15 handprints on the inner gates of the fort, left by the women who once inhabited it.

Sati Hands

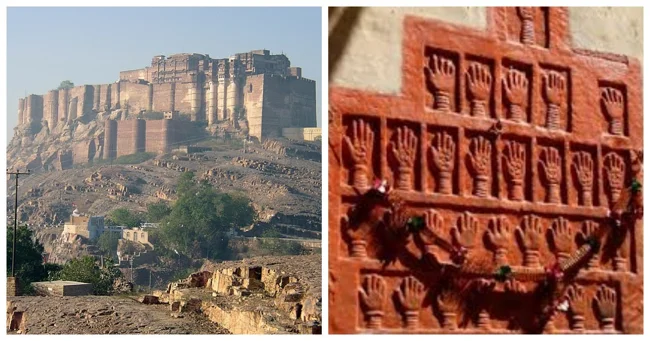

Mehrangarh Fort

Sati is an outdated Hindu tradition in which widowed women were expected to end their lives on their husband's funeral pyre. Hundreds of wives and concubines jumped into the pyre or were forced to do so in the name of tradition. The British were horrified by the act, so they banned it in 1829. But sati is too deeply ingrained in Indian soil to be abolished so easily. It took the Indian government to publicize sati in 1987 to formally create the Sati (Prevention) Commission Act.

But one incident was forever immortalized at Mehrangarh Fort back in 1843. The structure has seven gates, and the inner one is called Loha Pol, or Iron Gate. Tiny handprints are still visible on this gate. The handprints were left when Maharaja Man Singh passed away. Called the ‘sati hands’, they were left by the Maharaja’s consorts who jumped onto the funeral pyre after decorating the wall with the prints as a memorial.

But these prints only point to one chapter in the fort’s turbulent history. Before that, six consorts and 58 mistresses of Maharaja Ajit Singh also died in acts of sati in 1731. In fact, the fort’s foundation was bizarre from the start, foreshadowing one disaster after another within its precincts.

Bloody Foundation

In the 15th century, Rao Jodha of the Rathore clan in Marwar decided to build a huge fort on top of a hill that had natural defenses. The fort was to be called Mehrangarh, and the city that would arise at its base was to be called Jodhpur. But to build the fort, the hill had to be cleared of its current inhabitants - a decision that everyone but one agreed to without complaint. Chidyawale Baba, a saint who enjoyed feeding birds there, angrily cursed the king, declaring that his kingdom would suffer drought after drought if the fort was built.

There was only one way to appease the saint, and the monarch was not about to let it slip. To reverse the curse, one of the kingdom's citizens was asked to give his life. That man was Rajaram Meghwal, who was buried alive among the bricks and mortar of the fort in 1459. His sandstone memorial was built on the fort's premises, and his family continued to be supported by the state for generations.

The 35-metre rampart towering over the valley has caused death in other ways: tourists have slipped and fallen, Maharaja Rao Ganga died here under the influence of opium, and in 2008 hundreds died in a stampede at the Chamunda Devi Temple on the fort's premises.

Nevertheless, many continue to visit the fort for its majestic structures. The Moti Mahal and Phool Mahal sparkle with their mirrored walls. The gallery and armoury display the finest examples of Marwari painting and weaponry. There are also palanquins, rest rooms and a museum, most of which date back to the 17th century. But nothing compares to the handprints welcoming visitors to a world of misfortune and the Meghwal memorial, a testament to India's strange faith.