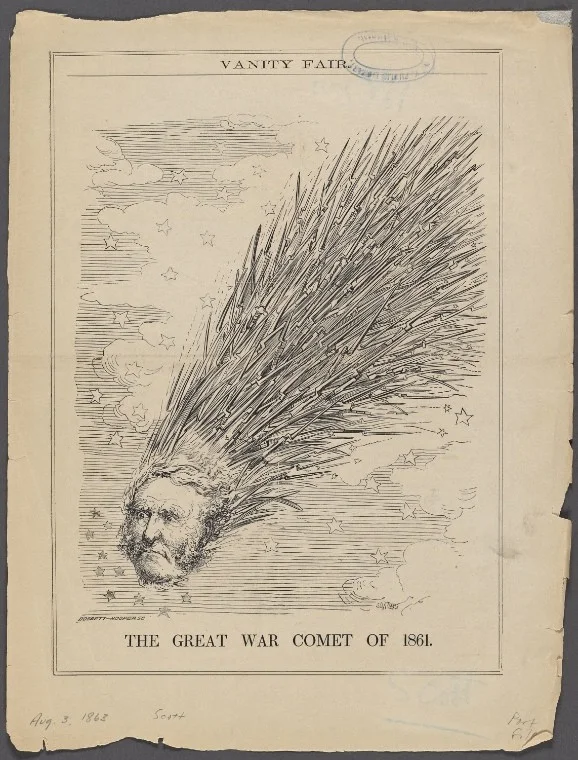

The 19th century was a wonderful time to be an amateur skywatcher. Between 1811 and 1882, eight great comets were visible from Earth, captivating scientists and laymen, and inspiring artists and composers.

Perhaps the most beautiful of these was Donati's Comet of 1858, which was the first to be successfully photographed. Three years later, another one appeared in the sky. The Great Comet of 1861 was exceptional in that it passed directly through the orbit of the Earth, and for two days the Earth was in the comet's tail. The tail also blocked the sun's rays during the day.

Discovery

Donati's Comet

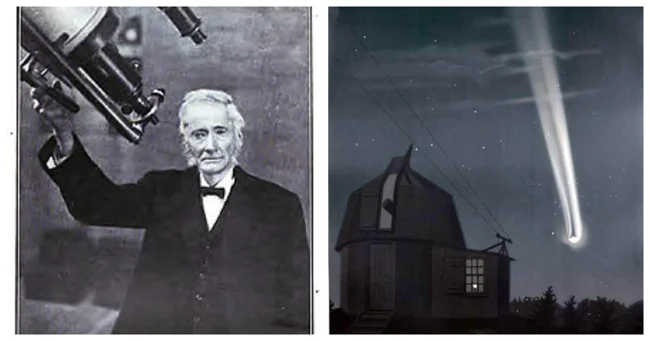

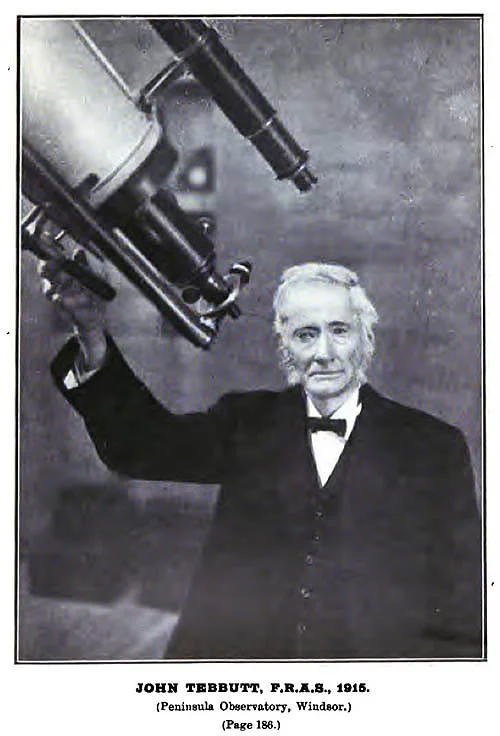

The Great Comet of 1861 was first spotted by sheep farmer and amateur astronomer John Tebbutt. On May 13, 1861, the young farmer, using an ordinary telescope, saw a faint star in the constellation Eridanus. Tebbutt checked his celestial maps but could not find any of the nebulae listed in that location. He guessed that it must be a comet, but he did not see a tail. Tebbutt observed the object for the next few days but could detect no visible change in its position until a week later when he saw it move about half a degree, confirming his initial guess.

The Great Comet of 1861

Tebbutt sent a letter to the Reverend William Scott, government astronomer at the Sydney Observatory, reporting his discovery, and also a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald. This letter was published on 25 May 1861, the young farmer's 27th birthday.

Communication between Australia and the rest of the world was slow in those days. Before news of the discovery had reached the northern hemisphere, the comet itself appeared in the northern sky. The first person in England to see it was probably William C. Bearder of Clifton, Bristol, who wrote to The Times on Sunday, June 30:

I discovered a brilliant comet near the north-west horizon at 2.40 this morning. It was visible until 3.20 this morning. It was as bright as Capella, and well placed for comparison. It was surrounded by a misty haze, but I could not see the tail... The daylight showed the comet and Capella almost simultaneously; therefore your readers will regard this as evidence that it is a brilliant object.

On the same day, Samuel Elliot Hoskins, a physician from Guernsey, observed:

At 9 p.m. a large luminous disk surrounded by a misty haze became visible on the northwestern horizon. At 9.40 it unmistakably assumed the appearance of a comet, with a large nucleus and a fan-shaped tail directed vertically to the zenith. It shone steadily until sunrise the following morning, moving with apparent rapidity, but with a slight declination, from northwest to northeast.

John Tebbutt

As summer approached and the days lengthened, strange phenomena began to appear in the sky. E. J. Lowe of Beeston reported: "The sky was yellow, auroral, like a glare, and the sun, though shining, gave only a feeble light... In our parish church the vicar lit the pulpit candles at seven o'clock, which shows that there was a feeling of darkness even though the sun was shining." J. R. Hind of London told The Times: "There was a peculiar phosphorescence or illumination in the sky, which I at the time attributed to auroral glare; others remarked on it as something unusual."

The changes in the sky were caused by the Earth passing through the comet's tail, as J. R. Hind explained in The Times: "Let me call attention to one circumstance connected with the present comet... It seems not only possible, but even probable, that during last Sunday the Earth passed through the tail at a distance of perhaps two-thirds of its length from the nucleus."

Tebbutt Observatory

The comet's tail took the form of a large nebulous disk about a quarter of a circle wide. As the comet moved away from the Earth, the tail grew longer, taking up nearly half the sky.

By midsummer, the comet had become bright enough to cast shadows, even though its nucleus was only a few degrees above the horizon. On the night of June 30–July 1, 1861, the famous comet observer J. F. Julius Schmidt watched in awe as the Great Comet cast shadows on the walls of the Athens Observatory.

By mid-August the comet was no longer visible to the naked eye, but could be observed with telescopes until May 1862. An elliptical orbit with a period of about 400 years was calculated, indicating a previous appearance around the mid-15th century and a return in the 23rd century.

The discovery of this comet made young John Tebbutt an astronomical hero and introduced him to astronomers around the world. In 1864 Tebbutt built a small observatory and installed several instruments, including a 3¼-inch telescope, a 2-inch transit instrument, and an eight-day, half-second box chronometer.

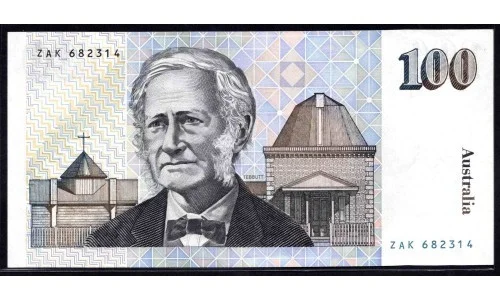

Over the next forty years, Tebbutt published many high-quality observations of comets, minor planets, stars, eclipses, and his reputation grew steadily. In 1881, Tebbutt discovered another comet. Although not as impressive as the Great Comet of 1861, it demonstrated his dedication and perseverance as a serious amateur astronomer. John Tebbutt was elected the first president of the British Astronomical Association branch, which was established in Sydney. He retired from systematic astronomical work at the age of seventy in 1904. John Tebbutt died in 1916. His memory was immortalised on the back of the Australian hundred dollar note.

Add your comment

You might be interested in: