Mere's diary: a 4,500-year-old papyrus that describes in detail the construction of the Great Pyramid (9 photos)

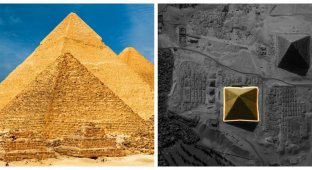

The Great Pyramids of Giza are one of the world's greatest mysteries: how did an ancient society build such massive structures without the aid of technology? The first and largest of them, the Pyramid of Khufu, is 146 meters high. The mystery of the pyramids may never be fully solved, but some discoveries have helped us understand how some of the impossible results could have been achieved.

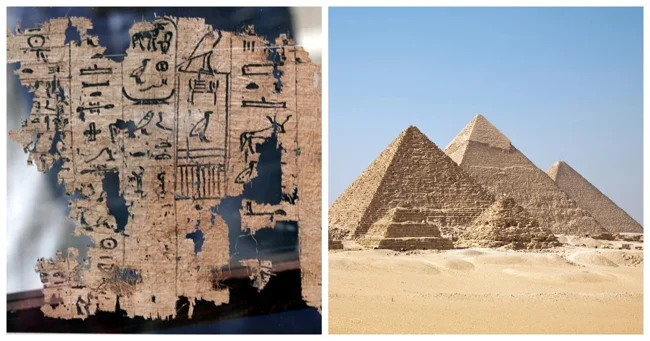

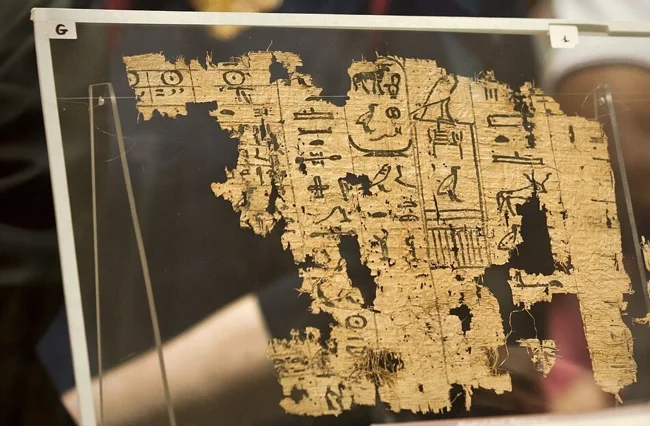

One such discovery was made in 2013 in a place called Wadi al-Jarf, which was an ancient harbor on the coast of the Red Sea. While excavating several stone buildings and man-made caves used to store wooden boats, archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard discovered entire rolls of papyrus. Some were several decimeters long, while others were fragments. They were written in hieroglyphs, as well as in the hieratic script that the ancient Egyptians used for everyday communication. Some of the papyri were even dated to the "year after the 13th cattle count" of King Khufu, that is, around the 26th or 27th year of his reign. This makes them the oldest papyrus documents ever found.

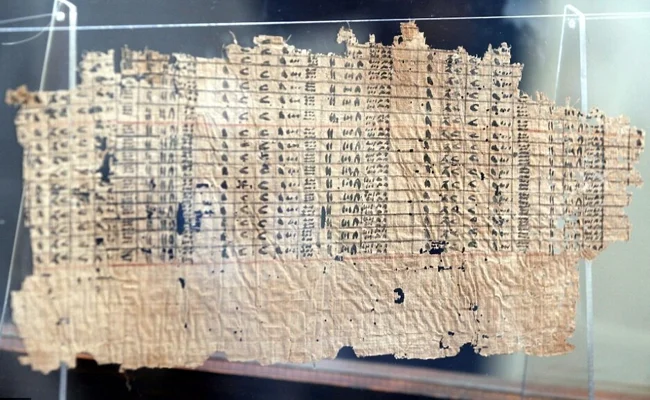

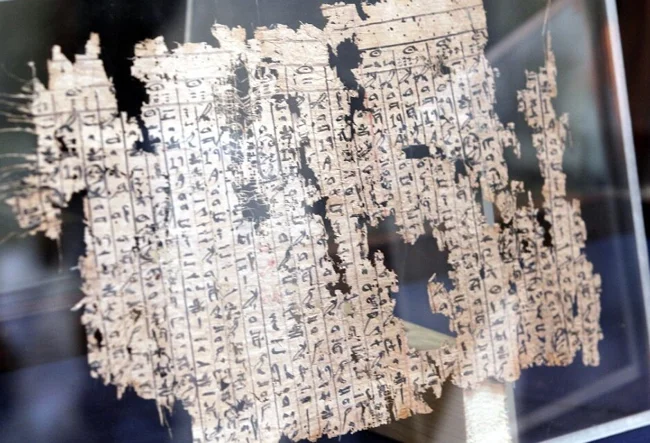

Even more astonishingly, the papyri were written by people who had been involved in building the Great Pyramid. Some were ledgers detailing the movement of bread, beer, grain, and meat to feed the 20,000 people scattered around the pyramid, quarries, and transport crews. The documents were laid out like a modern spreadsheet, showing what was needed, what had been delivered, and what was still to be delivered.

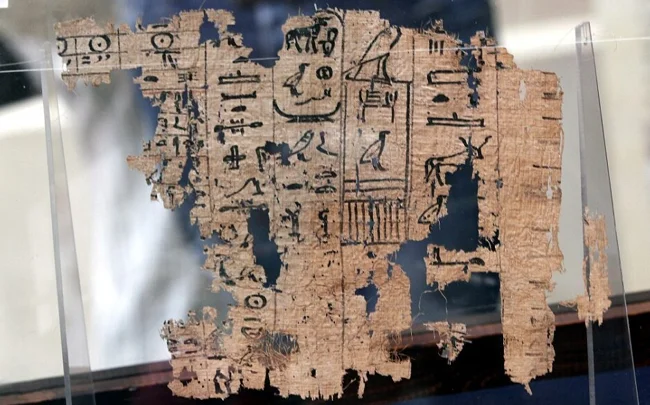

Others were diaries detailing daily activities. Among them was one written by an "inspector" named Merer. He led a team of about 200 people who traveled from one end of Egypt to the other, collecting and delivering various materials. Their main job was to transport limestone blocks from the quarries of Ro-Au (Tura) to the construction site at Giza, located about 15-20 kilometers away. The pharaohs used limestone from Tura, a city on the Nile known for its limestone quarry, for the outer casing of the pyramids. This was later removed, revealing the roughly hewn granite blocks visible today. Thus, Merer's diary chronicles the last known year of Khufu's reign, when the ancient Egyptians completed the Great Pyramid.

Mere's notes describe his crew hauling stones from Tura, filling boats with the stones, and carrying them up the Nile to Giza. The trip took two days. The return journey, empty, took only one day. During each ten-day Egyptian week, the crew made the round trip between Giza and the quarries at Tura two or three times. This could only have happened during the annual flood, when the high waters of the Nile made it more navigable for heavily laden ships. It has been estimated that the boats could carry a load of 70-80 tons, or about 30 of the 2.5-ton blocks used to clad Khufu's pyramid. This means that Merer's crew could transport around 200 blocks per month, and up to 1,000 during the period when the river and canals were navigable.

Merer also mentions subordination to "the noble Ankhkhaf" who served as the head of the "entrance to the Khufu Basin", probably an artificial lake used as a staging post on the route from Tura north to the Giza plateau. Ankhkhaf was Khufu's half-brother and appears to have supervised the pyramid project during its construction. This was the first time that a specific individual was identified as overseeing the construction of the Great Pyramid. The diary also mentions the original name of the Great Pyramid, Akhet-Khufu, meaning "Horizon of Khufu."

Zahi Hawass, an Egyptian archaeologist who was the chief inspector of the pyramids and the Minister of Antiquities, says it is "the greatest discovery in Egypt in the 21st century."

“The records of Merer and Dedi help us to understand the geography of Lower Egypt and the network of canals and harbours that allowed the transport of stones, workers and supplies to the pyramid building site,” writes Egyptologist Dan Potter. “The crews were highly skilled and versatile, not only transporting materials for the pyramids and temples but also managing warehouses, possibly building a dock and participating in mining operations.”

It is believed that the notebooks and ledgers were left behind in Wadi al-Jarf after the team had completed their final task. "I believe that because of the king's death... they simply stopped everything and sealed the galleries, and then when they left, they buried the archives in the area between the two large stones that sealed the complex. The date on the papyri is probably the last date of Khufu's reign, the 27th year of his reign," says Pierre Tallet.

After the closure of the complex, work under Khufu's successor, Khafre, took place at Ain Sokhna to the north.