The Great Diamond Scam of 1872 (9 photos)

It is not for nothing that greed is one of the deadly sins. The thirst for profit sometimes obscures people’s eyes with such a thick veil that they are ready to believe in anything.

The gold and silver rushes of 1848 in California and 1859 in Nevada ignited the American West. Thousands of prospectors, hoping to find riches in the mountains, began to move to the west coast of the United States.

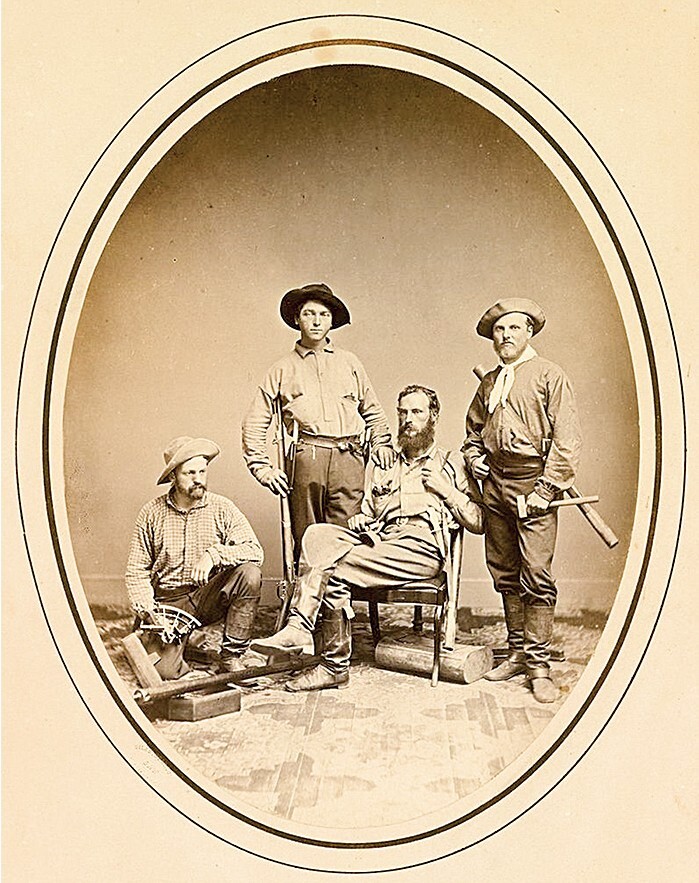

Philip Arnold and John Slack

Mining towns sprung up and bankers began creating mining companies to make millions of dollars for themselves and other investors. This greed and mining rush provided the perfect environment for the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872.

This deception was recognized as the most gigantic and blatant scam of the century, but what really happened?

Cunning plan

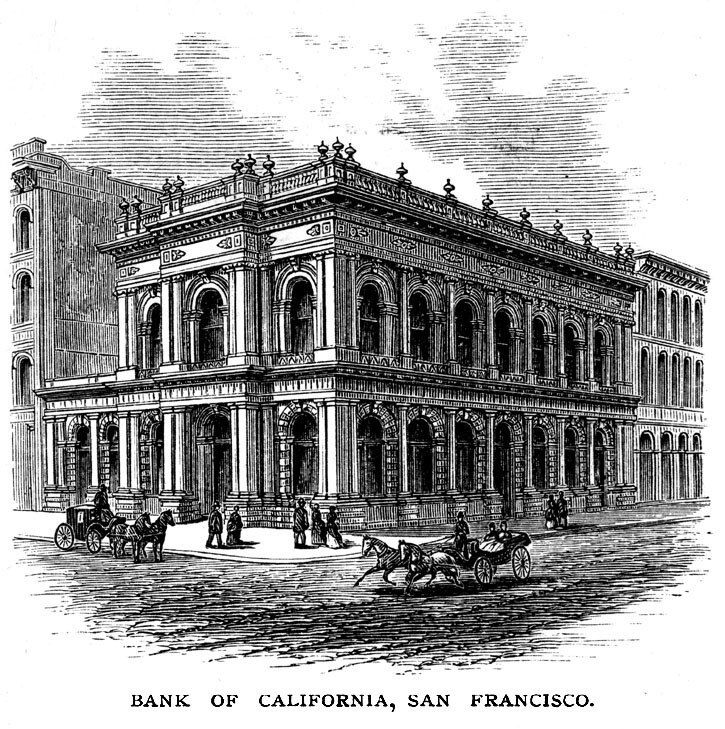

The Bank of California agreed to store the bag of diamonds the men claimed they had dug up, and rumors of the supposed find quickly spread

One night in 1871, two cousins and prospectors, Philip Arnold and John Slack, showed up on the doorstep of George D. Roberts' office in San Francisco. George Roberts was a financier, broker, and businessman who was described as a man willing to act quickly—perhaps too quickly—when opportunities arose.

Brothers Arnold and Slack asked Roberts if they could go into his office and leave something there overnight. After some pressure from Roberts, the cousins told the man that the leather bag they had was full of rough diamonds they had found in a gem deposit in a secret location.

Arnold and Slack said they intended to deposit the bag at the Bank of California, but the bank was closed at that late hour.

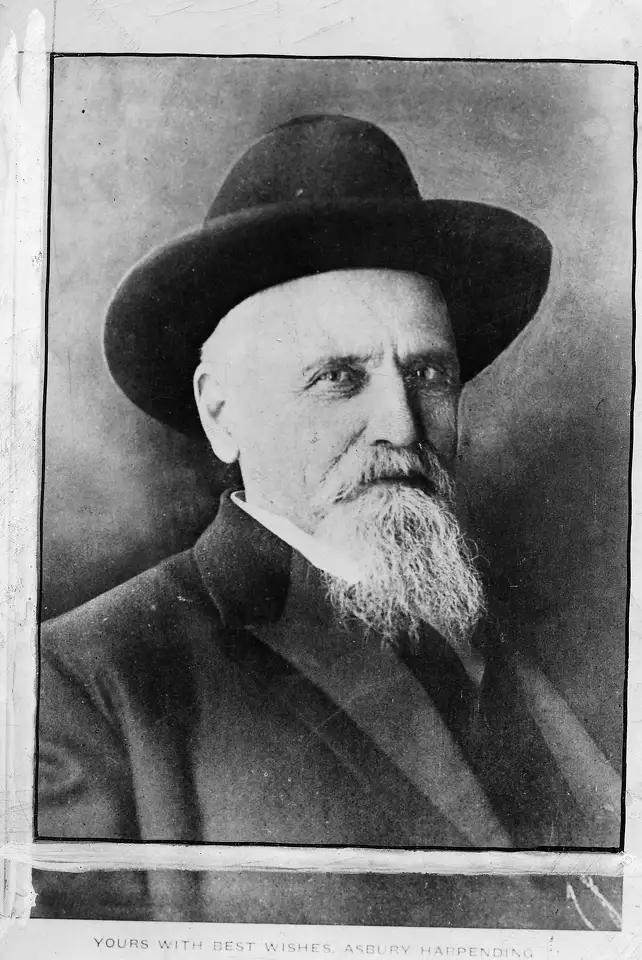

Arnold and Slack made Roberts swear that he would not tell anyone about the stones. But as far as George Roberts was concerned, keeping secrets was not his strong suit. Immediately after Arnold and Slack left the office, Roberts called William Ralston, the wealthy founder of the Bank of California, and a man named Asbury Harpending, often described as an adventurer and one-time potential Confederate knight.

Wanting to pad their bank accounts, Ralston and Harpending agreed to provide financial support to facilitate mining at the secret location. And then they set in motion a cunning plan.

Arnold and Slack knew that if they wanted to secure the financial support of bigger fish, they had to use bigger bait. This meant that the couple returned to Roberts some time after the initial visit and told the financier that they had just returned from the diamond field.

Asbury Harpending

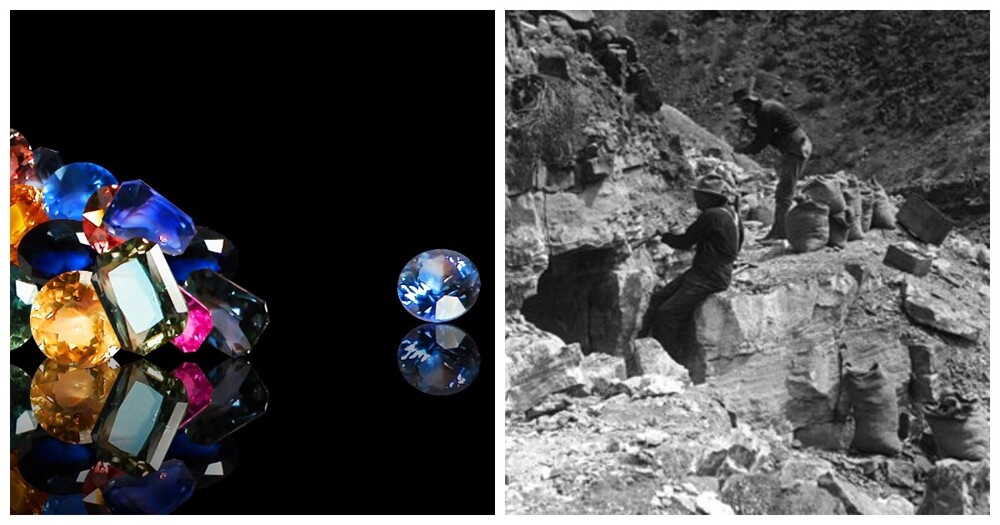

They collected about 27 kilograms of diamonds and rubies, the value of which is estimated at more than half a million dollars - a colossal amount of money for the 1870s. Roberts took the bait and convinced two other wealthy diamond entrepreneurs, General George Dodge and former Union Army officer William Lent, to join what looked like the diamond mining operation of the century, if not the millennium.

Arnold and Slack convinced financiers that they would bring in even more gems worth millions of dollars in exchange for an investment and a partial buyout of $50,000 in cash. When rough diamonds and other stones can be worth millions of dollars, a $50,000 ransom seemed like a fair deal.

Roberts and other supporters of the hoax did not know that Arnold worked for the Diamond Drill Co., a drill manufacturer in San Francisco that created diamond-tipped drill bits.

Industrial quality diamonds are incredibly strong and are still used to drill into ceramic, marble, granite and porcelain. The core of the drill contains tiny particles of rough diamonds that are welded into the metal to give the drill its strength. It is believed that the rough diamonds that Arnold and Slack had were taken from the Diamond Drill Co.

Other stones, such as rubies, garnets and sapphires, that the men brought with them, claiming to be from this top-secret diamond mine, were most likely purchased from Native Americans in Arizona. However, the trick worked. When the couple set out on their proposed third diamond-mining expedition, they went not to some windswept countryside in the American West, but to London. Using fictitious names, the con-artist cousins bought approximately $20,000 worth of uncut diamonds and rubies from a local gem dealer.

Miners in the Grand Canyon

Arnold and Slack returned to San Francisco and allegedly threw a bag containing thousands of rocks onto the pool table at Harpending's house so that Roberts, Ralston, Dodge, Lent and Harpending could see them. The men were blinded by the shine of hundreds of stones.

All the stones that Arnold and Slack presented to the men were real. However, they were of low quality and less valuable than they looked. Not all gemstones are good enough to be used in expensive jewelry, and some are of poor quality or cut and are worth next to nothing.

Tiffany & Co

After looking at a pile of gemstones lying on a pool table, the men decided that 10% of the stones from the pile should be taken to New York to be appraised by Charles Lewis Tiffany of Tiffany and Co Jewelers. A team of men brought the stones to Manhattan for evaluation, and they were joined by Congressman and one-time presidential candidate Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, Major General McClellan, and several unnamed high-ranking bankers.

After examining the stones, Tiffany determined that they were genuine and set the value at approximately $150,000, which meant that the remaining 90% of the stones from this latest “diamond field trip” were worth approximately $1.5 million!

Investors from California and New York formed the San Francisco and New York Mining and Commercial Company. To convince people to buy shares in this new company, trays of gemstones were displayed in well-known jewelry stores.

Investors came to Arnold and Slack and demanded that they take them to the fantastic mine and take with them Henry Janin, a famous mining engineer, to further evaluate the site. The cunning brothers agreed to these conditions, but insisted that the group be blindfolded during the final approach to their destination.

James T. Gardiner, Richard Cotter, William H. Brewer and Clarence King

In June 1872, the "inspection" traveled by train to a town called Rawlings in southern Wyoming and then continued on horseback. Knowing that the diamond mine did not actually exist, Arnold and Slack led the group in circles for four days, pretending to be lost. The group reached a "place" described as "a wide spit, overlooked by a cone-shaped mountain to the south."

It was only a few minutes before one of the men alerted the group to a diamond he had found in the mud, setting off a domino effect: within an hour, the men were effortlessly finding diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires. Mining engineer Yanin was delighted and declared that the deposit of precious stones was genuine.

The investors paid Yanin $2,500 but gave him thousands of shares in the company, priced at about $10 a share.

Returning to New York, Yanin quickly sold all his shares at four times the price, earning serious money.

Deception Revealed

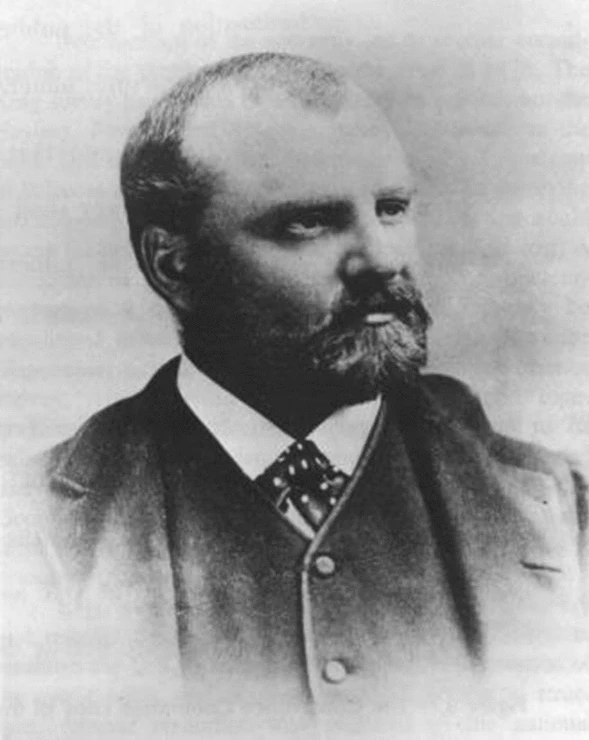

Clarence King

Arnold and Slack tried to get as far away from San Francisco and investors as possible and cashed out their shares. Slack walked away with $100,000, while Arnold received $550,000.

Together, they defrauded investors out of more than $650,000, which is worth more than $17 million today. Money in hand, Slack seemed to disappear from the face of the earth, and Arnold returned to his family in Elizabethtown, Kentucky.

The truth about the diamond mine came to light thanks to geologist Clarence King, who was working on a major survey of agricultural and mineral resources for the US government in the areas surrounding the Arnold and Slack mine. By chance, one of King's geologists encountered Ianin on a train bound for California and was shown some of the diamonds, rubies and sapphires found at the site. And then both realized that something did not add up: rubies and sapphires are rarely found in the same places as diamonds, and geologists paid another visit to Ioannina in San Francisco to learn more about the miraculous find.

In October 1872, King and a party set out on their own to explore the Arnold-Slack site, and almost immediately they began finding garnets, spinels and amethysts, but no diamonds. A few days later, King saw a diamond "sitting precariously on a thin stone," which raised suspicions because it could not have remained in place for the hundreds of years it took for a diamond to form.

The team then discovered that each anthill had several openings in addition to the main entrance and exit. These additional holes were 15-20 centimeters deep and looked as if they had been made with a stick or cane, and when the hill was excavated, a gem was found in each of them.

Investors, bankers, mining engineers and even Charles Tiffany were fooled. It turned out that Tiffany knew almost nothing about uncut gems, and although Yanin was deceived and his reputation tarnished, he managed to walk away with a ton of money from the sale of his shares, so it was not so bad for him.

Investors sued Arnold and Slack, but nothing came of it, and both continued to live as if nothing had happened. The excitement created by the gold and silver rush in the American West and the mining of precious stones was so exciting that investors and experts, anticipating multimillion-dollar profits, did not notice that a scam, grandiose in its simplicity, was being played out right in front of them. Although the technically enterprising brothers, in general, did not deceive anyone. They simply gave those who wanted what they wanted.