Forensic botany and witness trees that help solve murders (9 photos)

It may seem that only serious evidence is important for investigating a crime - fingerprints, biological material, witness statements. And the help of some flowers and leaves... It’s funny!

However, the most common branches, seeds and even tree pollen can help in the investigation of cold cases.

"Baby Doe", later identified as Bella Bond, was found dead in 2015. Before releasing her name, police released a photo of her that was shared millions of times.

In June 2015, a woman walking her dog on the shores of Boston's Deer Island came across a garbage bag. She opened it and found the body of a dead girl, wrapped in a fleece blanket.

The mother and her drug addict partner were involved in the death of little Bella.

It was a very difficult matter. The victim's clothes turned out to be ordinary, and the water destroyed fingerprints and other evidence. The autopsy revealed almost nothing. A computer-generated image of a girl named Baby Doe went viral across social media across the country. But it didn't give any clues. Indeed, detectives knew nothing about her until they found pine pollen on her blanket. This made it clear that she was local, which significantly narrowed the scope of the investigation. By September, she had been identified and the suspects brought to justice.

Palo verde tree pods

For forensic botanists, plants represent a whole class of easily accessible, if silent, witnesses. They cannot turn their souls inside out or admit what they overheard. But when it comes to questions related to solving a crime - who, when and where - their mere presence is enough.

A unique seed pod found in a pickup truck may raise suspicion about the truth of a claim about a suspect's location. As happened in 1993 in Arizona with a murdered woman found under a palo verde tree. Or marijuana seized in different places can be analyzed by DNA, and identical varieties can be used to track down drug traffickers.

Arthur Köhler – forensic botanist and wood identification specialist

The first botanist to take up forensic science was Arthur Koehler, who, as a wood expert at the US Forest Products Laboratory, used his knowledge in a number of cases in the 1920s and 30s.

Koehler used his knowledge of tree taxonomy and cellular structure to testify about the origins of wood used in homemade bombs and weapons. Most famously, he served as the chief expert witness in the so-called Trial of the Century, the 1935 Lindbergh kidnapping case.

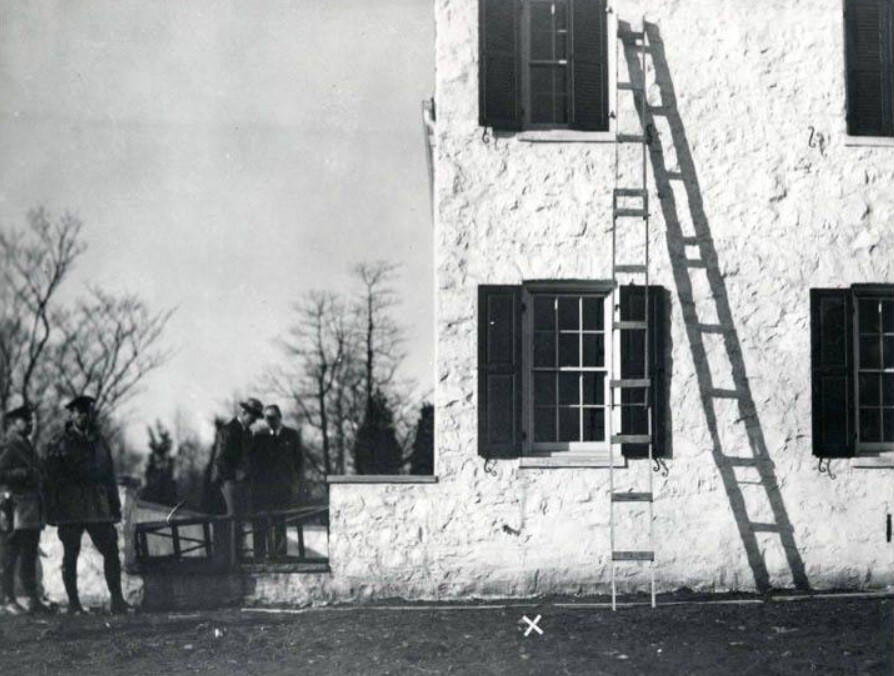

Crime scene - kidnapping for ransom and death of one and a half year old Charles Augustus Lindbergh - the son of the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh

When Koehler took the stand, the defense initially objected, calling him just a man with extensive experience in tree research. But by the end of the trial, Koehler had convinced the jury that, based on microscopic examination and his own extensive carpentry experience, he could pinpoint the origin of the ladder found leaning against the window at the crime scene. After he traced it to a lumber yard in the Bronx and matched one of the replaced beams to a wooden plank found in the attic of carpenter Bruno Hauptmann, Hauptmann was convicted and executed shortly thereafter.

And 90 years later, the work of the persistent Köhler lives on. Lots of nerds work as consultants. Digging into the specific mysteries uncovered by forensic botany, like most such research, is mostly sad and creepy. So, in 2015, a woman died in Taipei. It was initially believed that she died due to being hit by a car. Until they found leaves in her hair. Experts determined that they were from a potted plant several stories above the street, and that the woman jumped out of the window, hitting the plant as she fell. There was also an elderly man who was found cut into pieces throughout South Florida. Branches and leaves found in buckets containing his body parts matched a tree in the suspected killer's yard.

Despite all this drama, real forensic botanists note that their work is not so much a showy presentation of the necessary information, but a long and meticulous routine work.

Looking at plants - potted flowers, street flowers, bushes and trees, you begin to understand how closely they are woven into our lives. And death too. That tree, along which we glance fleetingly when running out of the house, looks at us much more attentively. And although such a scenario, of course, would not be desirable, perhaps this inconspicuous tree will help solve the murder if it happens.