How it happened: using a unicorn horn to test food for poisons (10 photos)

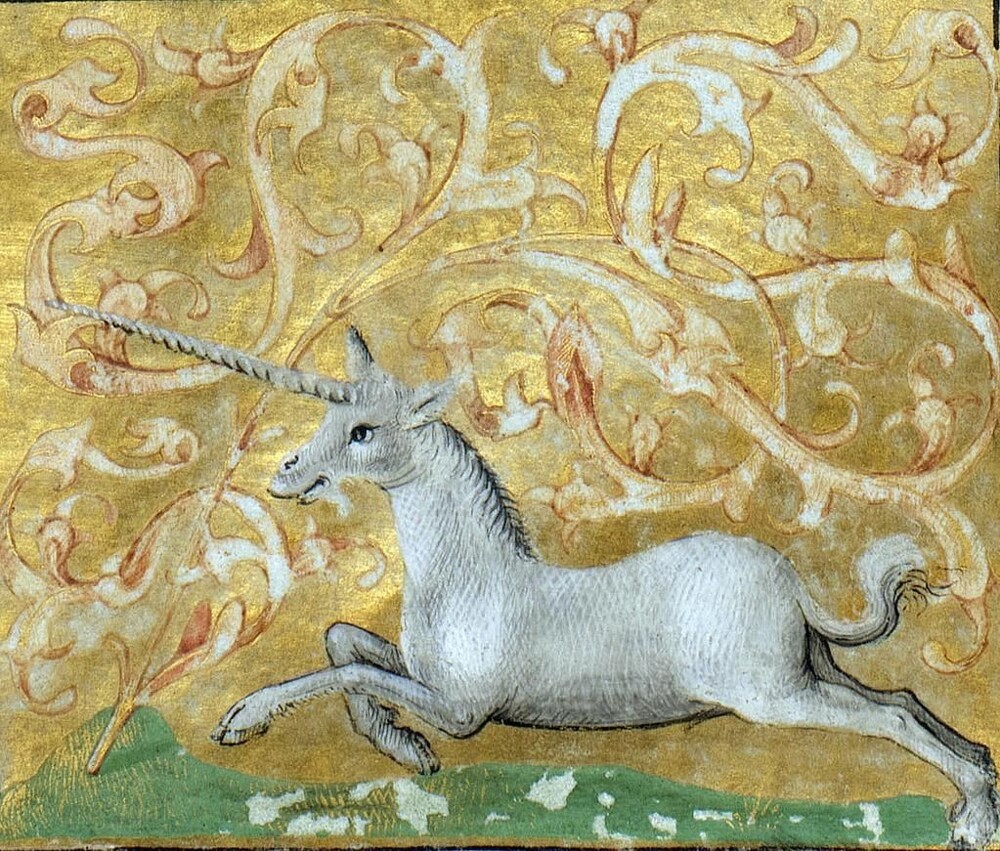

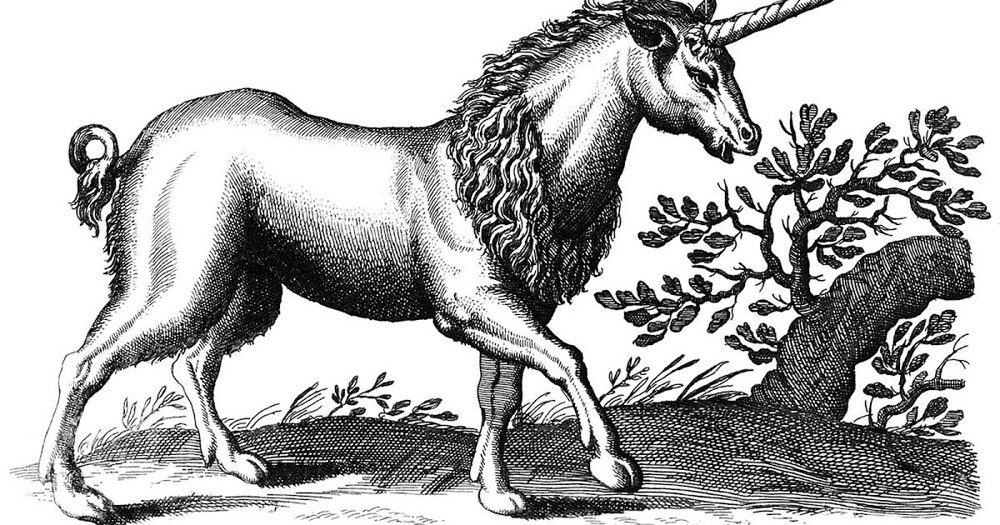

You don’t exist, but at the same time crowds of people who want to catch you, tear you apart and use every piece with feeling, sense, and arrangement are chasing after you? Congratulations: you are a medieval unicorn.

Although this animal is fictional, during its, so to speak, non-existence, the poor fellow got a fair amount of trouble. The graceful ungulates are chased by dogs, lured into traps with virgins as bait, and killed for their magical properties. According to ancient scholars such as the Greek physician Ctesias, the magical properties of the horns included purifying water and expelling poison from food.

The brightest luminaries from Aristotle to Leonardo da Vinci believed that unicorns exist. And the Aesculapians in the Middle Ages began to claim that the purity of unicorn horns makes it possible to detect poison. This claim made horns a popular item among royalty and the wealthy. European nobles have been known to use horns to determine if their food was lethal.

But how do you get a unicorn horn in a world where there are no unicorns? And that's a good question.

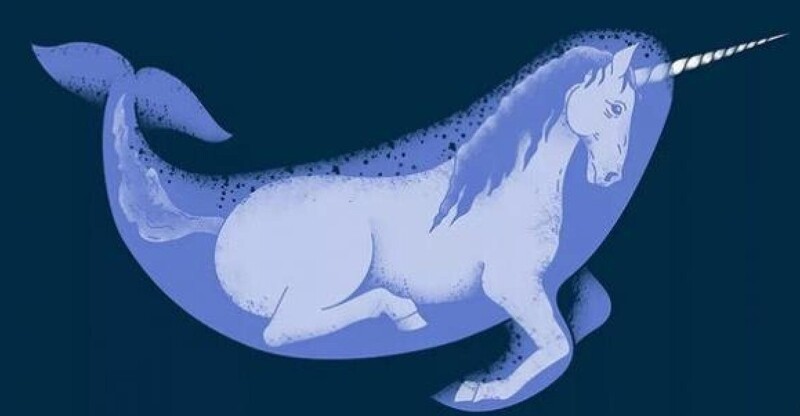

Sometimes the answer was the horn of a rhinoceros or walrus. But most often they took what is now considered one of the most expensive materials in all history - narwhal tusks. Narwhals are small whales that live in the Arctic, and their single tooth can reach 30 centimeters in length (or more) and curls to a point. They have long been hunted by the Canadian and Greenlandic Inuit, as well as the Vikings. In the early Middle Ages, traveling the seas, the Vikings hunted animals and obtained narwhal horns, which they sold without revealing their true origin. These horns became so symbolic that by the 12th century the twisted shape of a narwhal's tusk had become the common image of a unicorn's horn.

Narwhal horns

Their potential mystical powers have made them almost priceless rarities. In his work “The Unicorn Horn Glass,” art historian Guido Schönberger noted that “among the things that man sought to protect life and prevent death, none was so highly valued as the unicorn horn.”

Snow-white unicorns were a powerful symbol. Often their cleansing powers were attributed to a holy connection with Christianity and Jesus Christ. In other cases they symbolized love. But none of these high associations stopped royalty from purchasing horns that belonged to dead unicorns. Lorenzo de' Medici owned a narwhal tusk that was worth 6,000 gold coins, and Queen Elizabeth I was rumored to have received one worth £10,000 (the price of an entire castle). Danish rulers were once crowned on a throne made of unicorn horns.

Tomas de Torquemada

Even the Grand Inquisitor Thomas de Torquemada, the founder of the Spanish Inquisition, took a piece of horn with him on his trips. However, Thomas’s proactive measures can be understood: the insidious heretics could easily send the inquisitor to the next world by sprinkling some dirty tricks on him.

A simple check

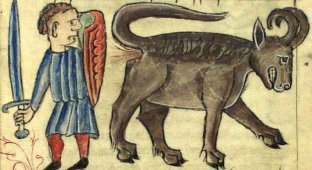

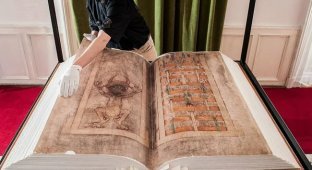

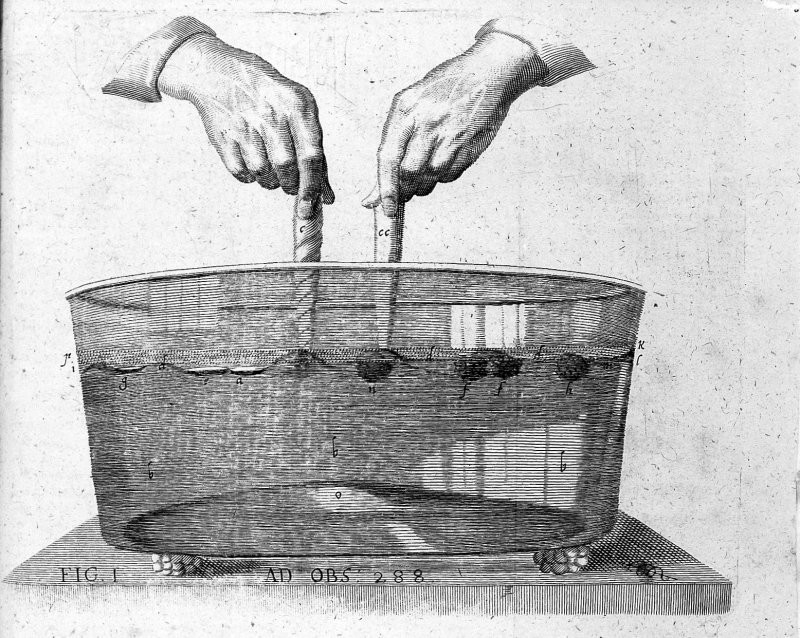

There were many ways to use the not-quite-unicorn horn. Crushed narwhal tusk was sprinkled on wounds and ingested to cure illness. But most often it was used to detect poison. Pieces of tusk were used to make cups, knife handles, amulets to wear around the neck, and even smaller pieces were used to test food and wine. The poison was detected if the bone changed color or began to fog. The complete absence of successfully discovered poison did not stop the antler trade.

Poor taster

For the nobility of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, poisoning was a common way of eliminating competitors and undesirables. It can be assumed that most royals died from natural diseases. But the undetectability of the poison in the years before the advent of modern medicine gave rise to healthy suspicion among those who had many enemies. The vengeful Medici were big fans of unicorn horn, and Mary, Queen of Scots wanted to try it for herself while she was a prisoner of her cousin, Elizabeth I. But in addition to unicorn horn, royals usually forced a servant to taste their food. Obviously, this method was much more effective.

Jan Vermeen Cup made from supposed unicorn tusk

With the beginning of the development of science and evidence-based experiments, belief in the miraculous properties of horns began to fade. And these days, unicorn horns, which in fact are not unicorns, remain only in museums as entertaining exhibits.