Inflated chickens, milk with lye and other tricks of sellers in pre-revolutionary St. Petersburg (5 photos)

Nowadays, replenishing supplies couldn’t be easier: come to the hypermarket, take hermetically sealed products, pay and forget about everything for a week. Or simply place an order through the app and wait for the courier. Housewives of the 19th century could not even dream of this. It was very difficult to find quality goods and honest sellers; there were plenty of scammers and dishonest businessmen in the city.

At the end of the 19th century, the “Complete Cookbook of an Experienced Housewife” by Ekaterina Avdeeva was popular, where, along with recipes, advice on housekeeping was also given. Along with the obvious recommendations (shop in trusted places, don’t go cheap, choose fresh products), there were also some rather exotic ones. If you listen to them, then it would be worth going shopping with a young chemist’s kit.

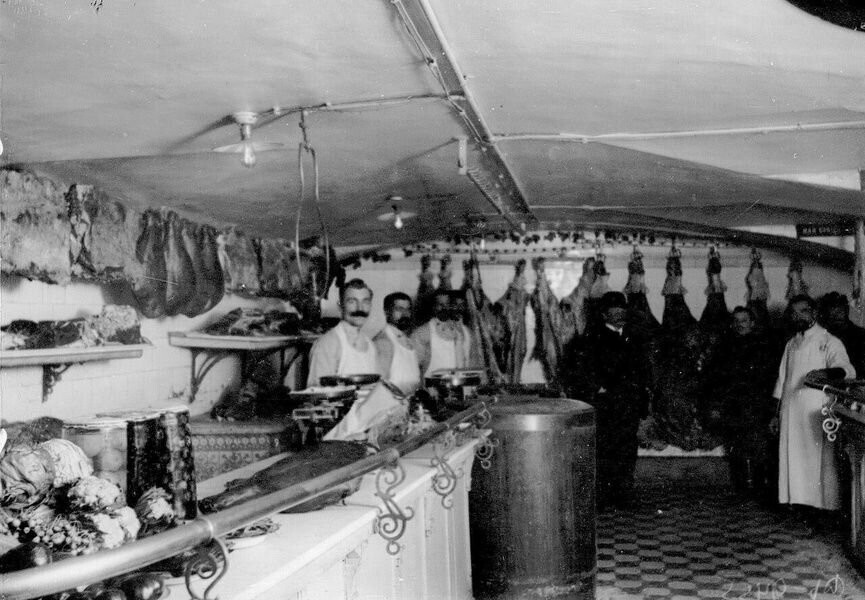

Buying sausage was a big risk, because most often it was made from unusable scraps, in the worst case, even spoiled. If you really liked the product, it was worth checking it for freshness. To do this, they took a piece of sausage, threw it into water and brought it to a boil, and then added lime water, which was freely sold in pharmacies, to the broth.

“If the sausage was made from spoiled meat, then when you pour lime water over the mixture, a special gas will be released from it, similar in smell to that released from latrines.”

Stale beef was smeared with blood to make it look more appetizing, and skinny chickens were sold at the price of first-class chickens, after being inflated. To prevent air from escaping, the bird's back hole was sewn up. In this way, rogue sellers managed to do this even with calves.

But the tow inside the carcass did not indicate malicious intent, although it alarmed many housewives. It helped keep meat fresh longer without affecting weight.

Eggs are not so sensitive to storage conditions, but obviously spoiled copies could still be found on the shelves.

“Sometimes an egg very unceremoniously speaks of its unworthiness, striking the sense of smell with a bad odor. This type of egg, easily accessible to all customers who have a somewhat normal sense of smell, is called tumak.”

If everything was in order with the appearance and smell, then it did not hurt to carry out more expert checks. For not very picky beginners, it was enough to lower the eggs into the water and make sure that they did not float up. You could look through the shell into the sun or a candle: the fresh product would become slightly translucent in the central part.

It was considered the height of skill to determine everything by temperature, for which one had to lick the egg. Ideally, the blunt end should feel warmer to the touch than the sharp end. If this is not the case, you should doubt the seller’s honesty.

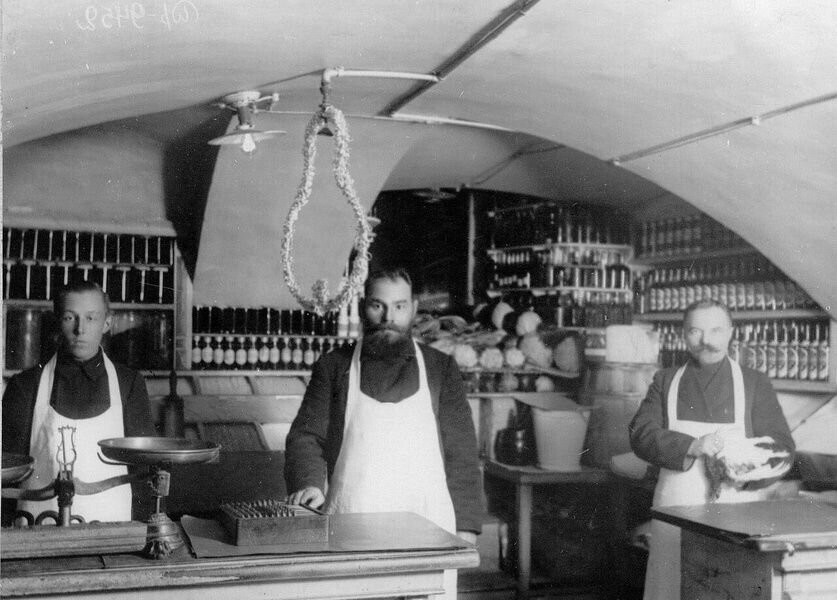

Finding high-quality, undiluted milk was not easy. Here and there on the counters there were jars with a bluish substance, which indicated the presence of water, with grains of flour and starch, which added viscosity, or even with alkali. Potash was added in the hope of increasing shelf life. To convict the seller of fraud, it was advised to add any acid to the milk. If it hisses, it means there is alkali.

The cottage cheese was also soaked in water, thereby increasing its weight.

Expensive butter was mixed with lard or grated boiled potatoes and then tinted. If you were suspicious, you should mash the piece in water and see if its color changes.

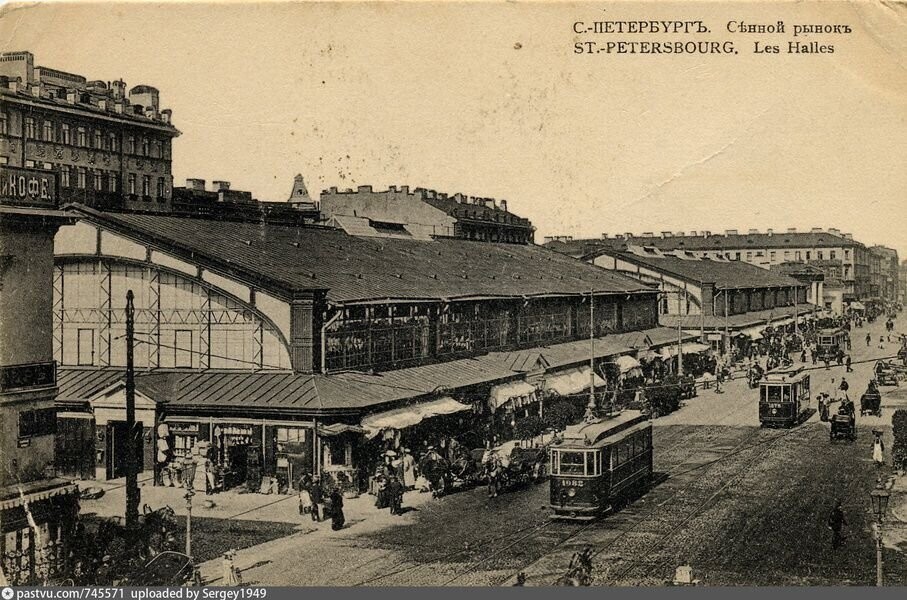

Such tricks were ubiquitous in the markets. Particularly distinguished was Senna, which the author of the manual characterizes as “a vast field of tricks of the food trade.” Therefore, thrifty housewives were advised to avoid it and make purchases in trusted stores.