Theft of 3 giant meteorites and 6 ruined Eskimos (9 photos)

This story is not only about an amazing discovery, but also about the inhumane attitude of ancient researchers towards indigenous peoples.

On the northwest coast of Greenland, the Iron Age began hundreds of years before Icelandic farmers brought iron there. Meteoric iron has been present in the region since at least 1000 AD, when a group of approximately 300 Eskimos settled in Melville Bay, bounded to the north by Cape York. The huge meteorites attracted Eskimos from all over the Arctic, and tools made from their debris allowed the Eskimos to transition from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. The Eskimos told explorer Robert Peary in the late 1800s a legend that three large meteorites represented an Inuit woman who was thrown from the sky by the evil spirit Tornarsuk along with her dog and tent. Perhaps the Eskimos simply mocked Peary by inventing such a legend, since John Ross and other polar explorers had never heard such a story. Most likely, the Eskimos believed that meteorites were natural formations.

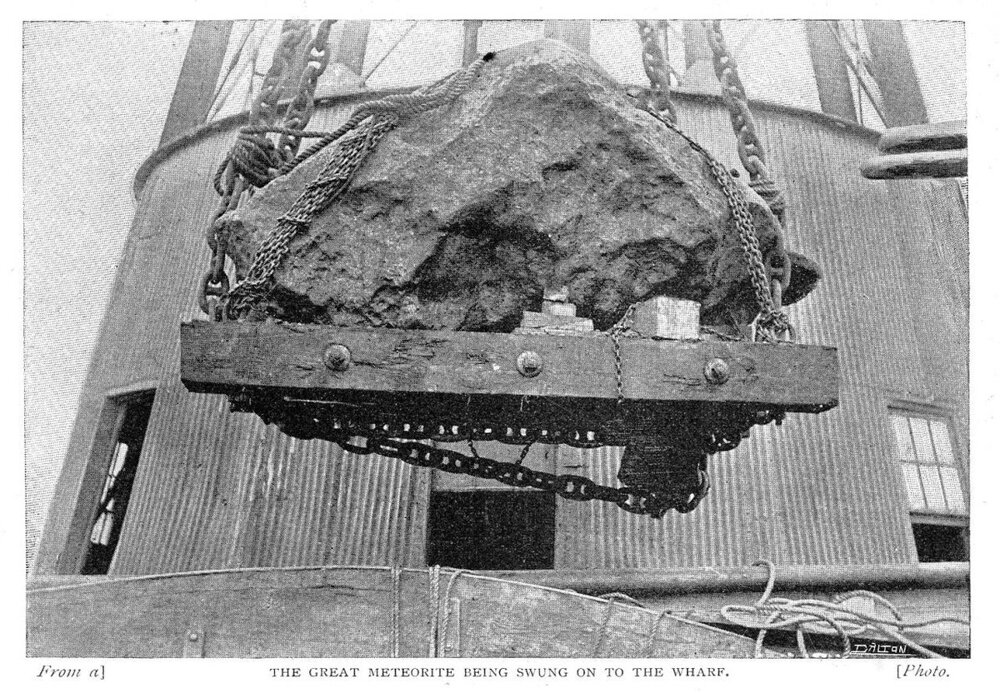

One way or another, for hundreds of years, "space visitors" were an integral resource for a group of Eskimos living in this barren part of the world. But now the three largest specimens from Cape York are stored in a completely different place. Robert Peary practically stole "Anigito" (Tent), "Woman" and "Dog" and they are now on display in the American Museum of Natural History. The Tent specimen is so massive that the supports for its display extend into the rock beneath the museum.

The meteorite impact site is located approximately 50 km northeast of Cape York. It disintegrated in mid-air over Innaanganek (Cape York Peninsula). The parent body of the meteorite blocks was 4.5 billion years old. The original meteorite weighed about 200 tons before breaking apart in the atmosphere. The fall is believed to have occurred more than 10,000 years ago.

Debris was present here long before the Melville Bay region was settled around 1000 AD. The Eskimos called this place "Savisavik", derived from the word "savik", which means "knife" or "iron". They called the "Woman" block "Saviksoah", which means "great iron".

Use by Eskimos

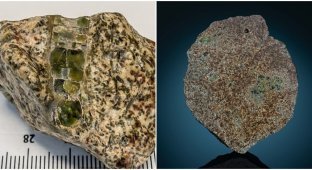

Inuit knife using meteorite iron

The journey from Cape York to Savisavik took 3 days. Temporary buildings on site were constructed from stone, providing shelter for workers. Several former meteorite block sites are easily recognizable, surrounded by piles of broken basalt, remnants of stone tools used by generations of Eskimos to mine iron.

“Woman” weighing 3 tons and “Dog” weighing 400 kg were the most intensively developed and the physical signs of prey are easily distinguishable on them. Archaeologists have discovered knives with handles made of deer antler and walrus tooth, axes with meteorite iron blades, and other weapons with tools. Cape York artifacts have even been found throughout Canada.

Discovery by outside researchers

Eskimo eats the feet of Robert Peary's wife

Early polar explorers were surprised to find that Cape York residents used iron-tipped weapons without apparent access to the metal either through trade or ore mining and processing. In 1818, Captain John Ross met the Eskimos living in Melville Bay, a group he described as the "Arctic Highlanders." John Ross became the first non-Eskimo to discover the presence of meteorites.

The Eskimos exchanged some of their iron-tipped tools with Ross, but did not reveal to him the location of the "mountain." Although Ross himself never saw the Savisavik site, his report on the expedition, which contained references to meteorite iron artifacts, later inspired Robert Peary.

"Strange Cargo" Peary

In addition to his mission to become the first person to reach the North Pole, Peary mapped parts of northern Greenland and wrote about the Eskimo way of life. Having failed in his 1894 goal of setting the record for the farthest journey north, Peary tried to save the mission in another way. By the late 1800s, Cape York had become less isolated due to the constant stream of polar explorers who were activeo traded with the local population. This may be why Peary was able to convince the Eskimos to show him the meteorite site, when they had refused to share its location with Ross decades earlier. Within a few years, Piri was able to gain the trust of the Eskimos. In his notes, Peary describes the Eskimos as "little brown wizards, very much like children and should be perceived as such." He wrote: "Their attitude towards me is a mixture of gratitude and confidence." Although he saw himself as their benefactor, not all Eskimos saw Peary in a positive light. He used their dogs to pull his sleighs and used the Eskimos themselves for heavy work.

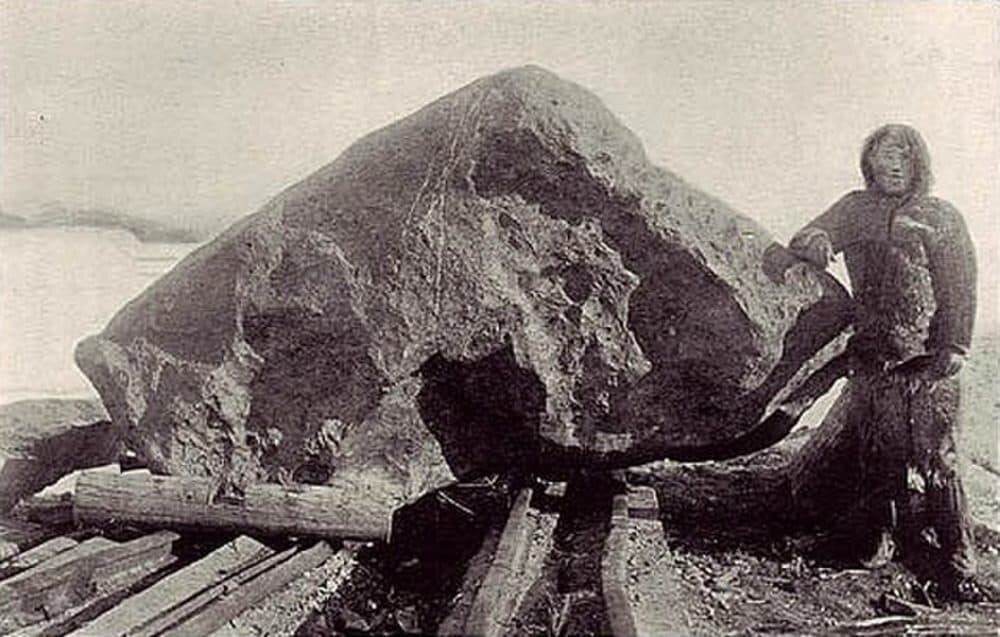

In 1894, Peary made an agreement with an Eskimo with whom he had become friends since the start of his expedition in 1891. He promised a gun in exchange for showing the location of meteorite samples. The Eskimo brought the explorer to the "Woman", "Dog" and "Tent".

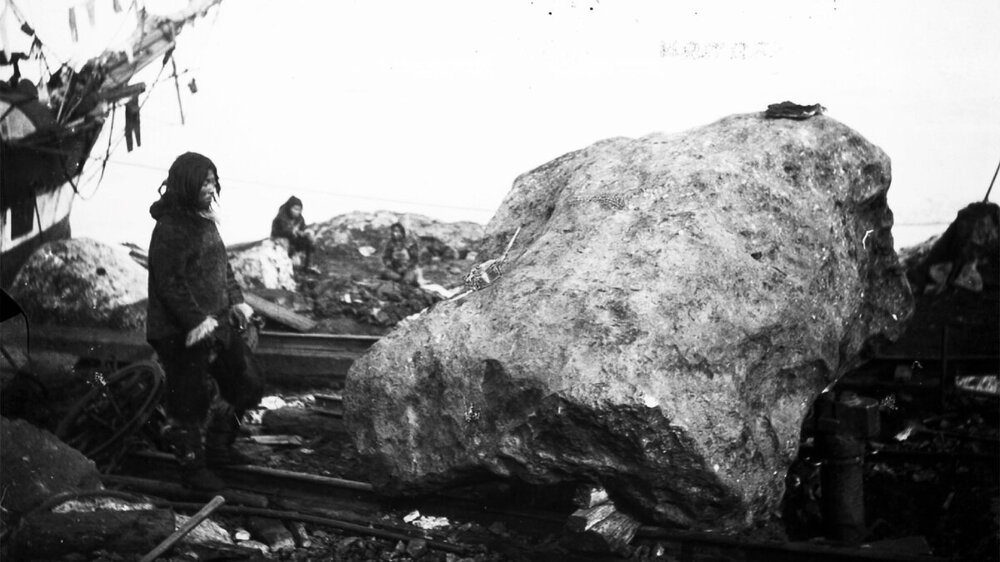

It is not clear how Robert Peary came to an agreement with the local residents. As far as is known, he never asked permission from the Eskimos before taking the meteorites. In 1895, work began on delivering all three blocks to America on the schooner Kite.

The research team was able to bring "Woman" and "Dog" to New York that same year, but "Tent" was too big a piece. Meteorites were transported to Peary's ship on ice floes. At some point, the ice broke under the “Woman”, and the sample was almost lost.

With "Tent" everything was even more complicated. Peary named the specimen "Anigito", the middle name of his daughter Marie, who was born in Greenland in 1893. Removing the meteorite from the ground and delivering it to the boat took more than a year.

Then begins the sad part of this whole story...

Piri and the Eskimos

When the meteorite approached the edge of the ship, the Eskimos abandoned it, perhaps out of superstition. Or simply fearing that its weight might crush the ship, but the meteorite was safely loaded.

With the cargo securely secured on board, the Nadezhda headed for Cape York, where most of the Eskimos were disembarked and paid for the work done.

Six Eskimos, however, remained on the ship. They went to New York with Piri and this was their biggest mistake.

In April 1897, six Eskimos arrived in New York. Far from their native Greenland, where their Inuit community numbered just 234, they found themselves in the heart of a crowded metropolis. The youngest of the group was seven-year-old Minik.

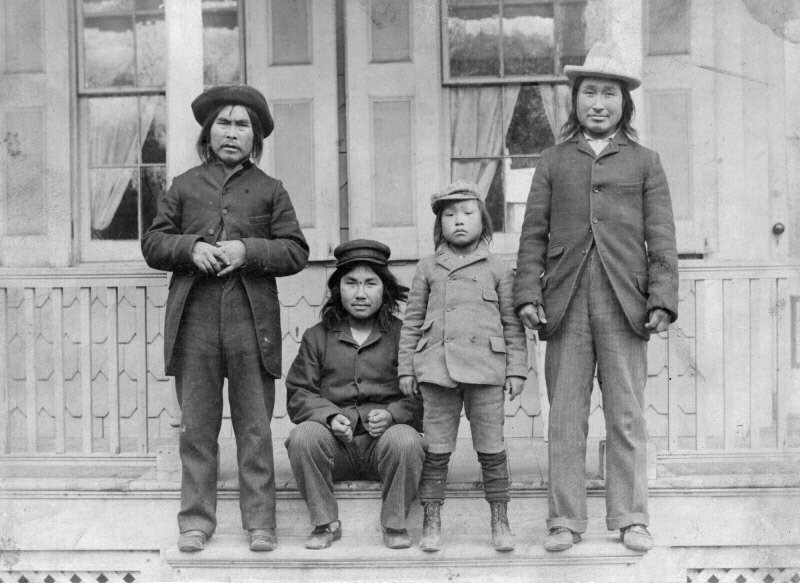

There are four Inuit in the photo, including Minik

Within a few months, four Eskimos died from diseases to which they had no immunity. Odin returned home to Greenland, leaving Minik alone in the huge city. Robert Peary literally abandoned them all, because he had more important things to do - he received a reward of $40,000 for meteorites.

Lonely Minick was adopted by William Wallace, the manager of the Natural History Museum. But despite being adopted and raised by the Wallace family, Minick never felt at home in a foreign country. More than ten years passed before he saw his native Greenland again.

In 1909, when Lieutenant Peary finally reached his dream, the North Pole, Minick returned home. This trip was sponsored by the researcher, fearing for his reputation in light of his achievements.

Minik felt like a stranger in Greenland too. He had already forgotten his native language and had to relearn hunting and fishing skills. Even a year after his return, Minik felt like an outcast and tried his best to adapt to life with the Eskimos.

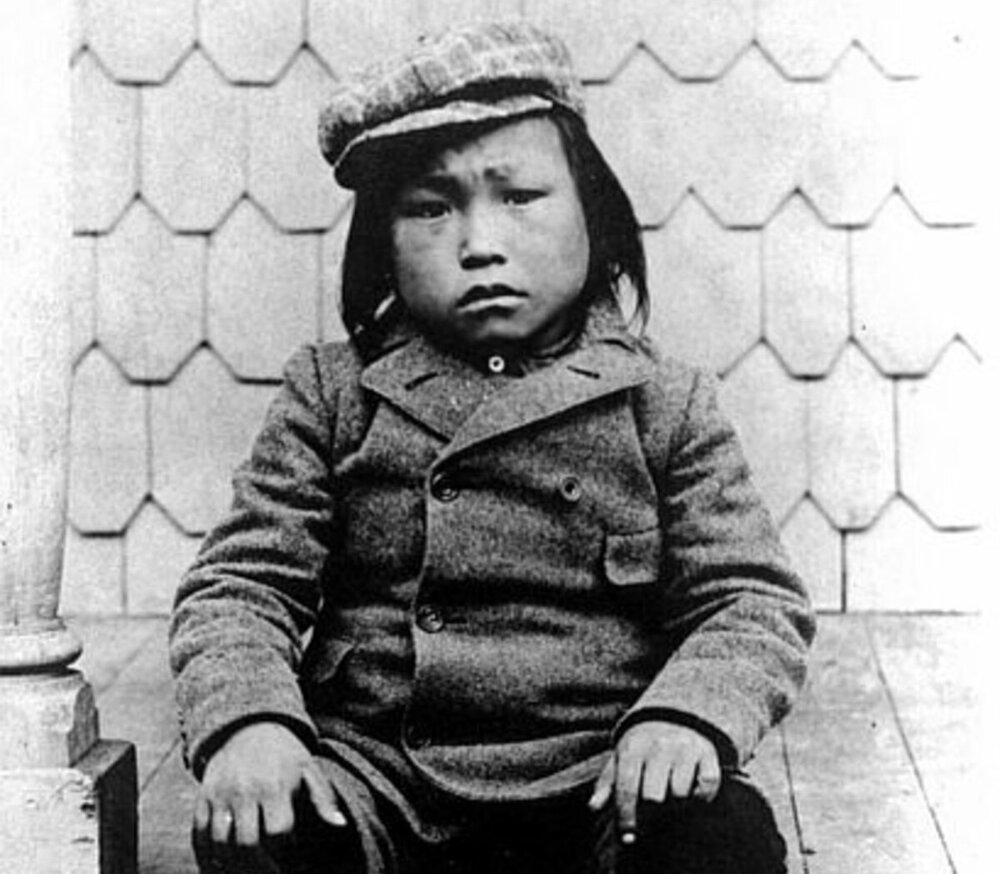

Minik

In a letter to an old friend, Minick later wrote:

"Why am I no longer fit to live where I was born? Not fit to live where my kidnappers brought me? Why am I like an experiment here and here? I have been tormented since the great white pirate interfered with nature and left me a helpless orphan, abandoned 10,000 miles from home?

In 1916 he returned to America and, two years later, fell victim to an influenza epidemic.

The American press later described this tragic story with the words: "While we celebrate the explorers who expand our horizons, the discovery of new lands often comes at the expense of the lives of men like Minick."