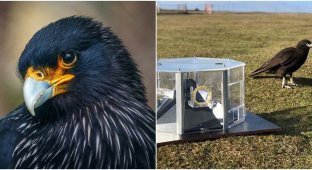

Honeyguide birds have learned to recognize the languages of local African tribes (3 photos)

Some African peoples use special languages to communicate with honeyguides. Researchers have discovered how these birds respond to calls made by local tribes.

Hunter-gatherers of some African tribes never search for honey alone. Going in search of hives, they enlist the help of experts - small African birds known as great honeyguides (lat. Indicator indicator).

Before starting a hunt, Africans make special sounds to call their feathered helpers. The birds understand this language and lead hunters to beehives, which are not visible from the ground and are hidden high in the cracks of the trees. Honey guides cannot independently reach bee colonies located in tree hollows, so they rely on human help.

When a bird finds a nest, it screams to bring people to it, who calm the bees with smoke, open the hollow and take away most of the honey, larvae and pupae. As a reward, the bird gets empty honeycombs made of wax (honeyguides are one of the rare animals that can digest wax; however, some of these tribes leave them some of the honey).

To learn more about how humans and birds interact, an international team of scientists from the University of California (USA) and the University of Cape Town (South Africa) went with two groups of experienced African honey hunters. The first included representatives of the Hadza people in Tanzania, the second included hunters of the Yao people in Mozambique. The distance between these two countries is more than a thousand kilometers.

In both locations, the researchers played back pre-recorded bird sounds made by members of the two tribes. This was done specifically to see how birds of the same species react to the same calls in different languages. The Hadza calls its feathered helpers with a melodious whistle, and the Yao with a loud vibrating trill.

In Tanzania, when scientists played indigenous Hadza sounds, honeyguides responded 81% of the time. When the researchers played “alien” sounds—yao—the birds responded to them only in 24% of cases.

In Mozambique, an almost identical picture was observed. When local Yao sounds were played, honeyguides responded 75% of the time, and when the Hadza played, they responded 25% of the time.

Such observations suggest that birds in different regions have learned to recognize specific signals from local hunters. Africans teach their children bird language from birth and thus pass on these signals from generation to generation. As for birds, scientists are not yet clear how they transfer such experience. Probably, young birds adopt it by observing their relatives.

The partnership between humans and honeyguides is a rare case of wildlife and humans collaborating for mutual benefit. It is based on the ability of two species to communicate.

A scientific work with the results of the study was published in the journal Science.