A ship "two in one". Engineering Thought and the USS Spuyten Duyvil (5 photos)

As we know, to create something new and technologically advanced, you need to experiment, and in the process, reject ideas to understand how reality differs from paper. This principle also works in the naval industry, when engineers and shipbuilders create different types of ships, not all of which become a series. For example, one of these was the American USS Spuyten Duyvil.

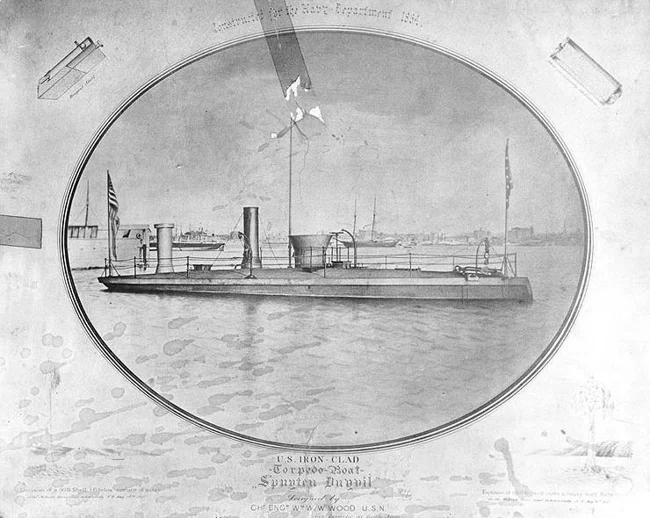

USS Spuytin Duyvil, circa 1864

The American Civil War marked the spread of two tactics at sea. The first was to use ironclads in open battles, and the second was to lay mines on enemy ships unnoticed using pole mines. However, mining required careful, unexpected actions under cover of night, which was not always feasible. Nevertheless, mining was considered very promising by both the Northerners and the Southerners.

Northern naval engineer William Wood, trying to improve Union ships, thought: what if we combine the capabilities of a torpedo boat with the protection of an ironclad? In this case, it would theoretically be possible to mine enemy ships right in front of the enemy at any time. Thus, the idea of an ironclad torpedo boat was born.

The work progressed quickly. On June 1, 1864, the Stromboli was laid down at the New Haven shipyard, later renamed USS Spuyten Duyvil. At the shipyard, the ship received several improvements and reworkings under the supervision of Samuel Pook. In September, it was launched and soon put into service.

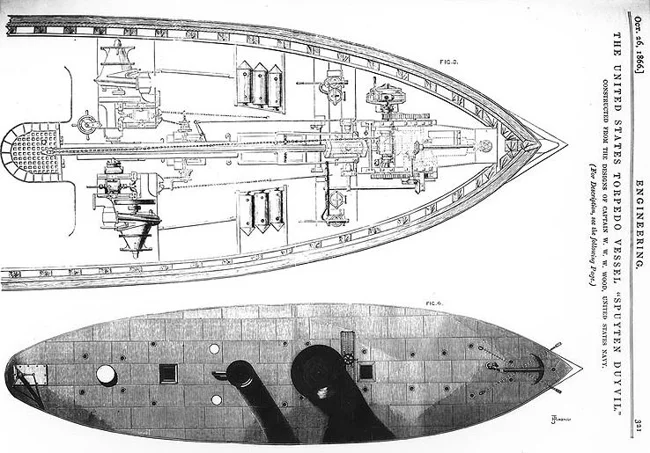

Ultimately, the armored destroyer looked like a monitor. Its length was 25.65 m, width 6.3 m, draft 2.29 m in normal mode (draft could be increased by filling the tanks with water), and displacement was 210 tons. The power plant with a capacity of 2400 hp consisted of one horizontal steam engine Mallory and Co, working on one screw. To fill the tanks, there were two pumps of the Andrews system, started by a pair of small engines. According to the design, the ship was supposed to reach a speed of 14 knots, but in fact it only reached 9. With full tanks, the speed dropped to 3 knots, but the noise from the engine was also reduced, which was very advantageous for surprise attacks.

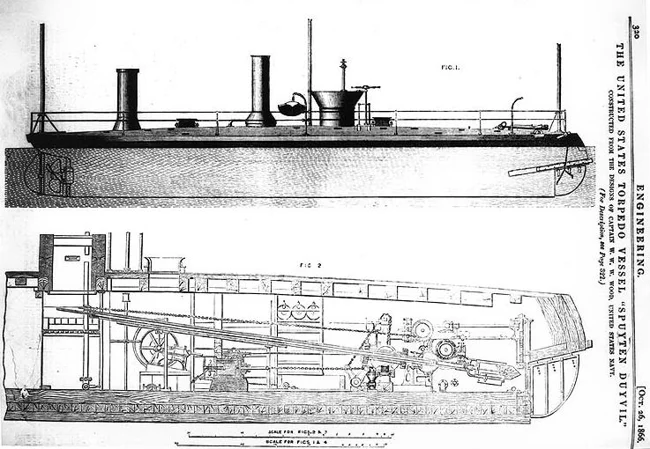

USS Spuyten Duyvil: side view (a section in the bow shows a pole for a mine) and a drawing of the mine mechanism. Images from the British Engineering magazine from October 26, 1866

The ship's hull was wooden and covered with varying amounts of 25-mm metal plates. This design was not very reliable, but cheap. The deck had three layers of protection (i.e. 75 mm), the freeboard had five layers (125 mm), and the most protruding part - the conning tower - was covered with 300 mm of armor.

The armament consisted of one spar torpedo - a pole mine. The ship could carry both ordinary 27 kg mines and 180 kg mines. All of them were cylindrical, filled with black powder and had a shock detonator. The mine apparatus was located in the bow and covered with two doors on a hinged mechanism. Next came the airlock and a reservoir for pumping out water, and behind it was a mechanism for movably holding the mine, extending it and changing the angle of attack.

Thus, the performance characteristics determined a unique method of using the ship. Being wide but not long, USS Spuyten Duyvil had low speed and limited maneuverability, being ideal for attacks in shallow water or rivers. Its low side could be lowered even further by filling the cylinders with water, which, coupled with its low noise, contributed to the unnoticed penetration of the enemy ranks and the surprise of the attack. And if surprise could not be achieved, then the enemy had to first "deal with" the low side, and then penetrate the armor, and this was not easy, especially in the heat of battle.

A top view of the USS Spuyten Duyvil, showing the mine mechanism and a general view of the upper deck. Images from the British Engineering magazine, October 26, 1866

En route to the target, the ship's crew prepared for the attack. The mine pole was inserted into a ball joint and pushed through it into the tank, and the mine was fed through a hatch from above and secured to the end of the pole. The hatch was then sealed and the tank with the mine was flooded. At the same time, the outer doors covering the mine port remained closed until the very last moment, so as not to lose speed.

Immediately before the attack, the outer doors covering the mine port were swung open. The steam engine pushed the pole with the mine out through the block. When the mine was under the hull of the ship being attacked, the cord was pulled out and the mine was detonated. The outer doors were closed, the mine port valve was sealed again, the reservoir was drained using a pump, and it was ready to accept a new mine.

This system proved its efficiency in two training launches shortly after the ship entered service, namely on November 25, 1864. After that, the ship was armed, and on December 5, she left for Norfolk. On December 15, USS Spuyten Duyvil arrived in the James River to participate in the blockade of Richmond.

It took the Northerners a long time to develop a plan to attack the city. Richmond was defended by a powerful Confederate flotilla, and it was covered by numerous underwater barriers. Deciding not to take any risks, the Union withdrew part of the fleet to attack Wilmington, leaving a small squadron in case of an attempt to break through.

And such an attempt was indeed made on January 23, 1865. The Union forces were limited to one ironclad monitor USS Onondaga, covered by USS Spuyten Duyvil and two gunboats, while the Southerners had three ironclads, three destroyers and five gunboats. With such an imbalance, the Union commander could think of nothing better than to retreat further and put USS Onondaga forward. He hoped that the Confederates would rush to this ship. And then USS Spuyten Duyvil would emerge from behind the monitor and blow up at least some of the attackers. However, nothing of the sort happened: the Southern pilots made a mistake, running two of their battleships aground and some of the other ships of the flotilla, thereby allowing the USS Onondaga to shoot them.

The USS Onondaga armored monitor on the James River. During the entire blockade of Richmond, it was covered by the USS Spuyten Duyvil

The battle ended, and the USS Spuyten Duyvil remained in the blockading flotilla until the fall of Richmond in April of that year. When the city fell, it was the armored destroyer that was tasked with clearing the fairway of the James River: for quite a long time, it blew up all underwater obstacles with mines.

After the war, there was no longer any need for a large fleet. This was especially true for non-seaworthy ships, which included the USS Spuyten Duyvil. It was transferred to the balance of a shipyard in New York and used to study various types of weapons, after which it was written off for scrap metal around 1880.

Thus, the USS Spuyten Duyvil became the first experimental attempt to combine an ironclad and a destroyer. And although from a practical point of view it was quite useful, it still had obvious limitations. To effectively use a torpedo boat with heavy armor, high speed was required, and therefore a large power plant. To accommodate it, a larger hull was needed, therefore more armor, which again reduced the speed.

And yet, the idea of building such ships existed for a long time, right up until the advent of rapid-fire large-caliber guns and classic torpedoes with a long range.