The Secret of the Coade Stone: How One Woman Changed the Face of Britain (13 photos)

At the eastern end of Westminster Bridge in London stands a majestic lion. It is a symbol of strength, power, and one of the most amazing materials in the history of architecture.

This beast is not made of stone or concrete. It is made of Coad stone, a man-made material that looks like the natural one, but has unique properties. It is resistant to time, weather, and even corrosion.

Stone Sphinx in Croome Park

For over two centuries, it has retained its original form, striking in its strength and detail. How did it do it?

Despite its name, Coade Stone is not a stone at all. It is a type of high-fired ceramic. It was created at very high temperatures, which made the material dense, waterproof and durable.

It is due to these properties that Koudsky stone has become an ideal material for creating decorative elements of buildings, sculptures and facades.

Eleanor Coade: A Woman in a Man's World

A plaque by Eleanor Coade at St Nicholas Church, Bramber, West Sussex

The secret to the success of Coade stone is a woman named Eleanor Coade. Born in 1733, she lived to be 88 years old and became a true innovator in the world of architecture.

The daughter of a wool merchant, she had no experience in the production of artificial stone, but she had a rare talent - to see the potential in people and ideas. In 1769, she met Daniel Pincott, a craftsman who knew the secret of making artificial stone but needed funding.

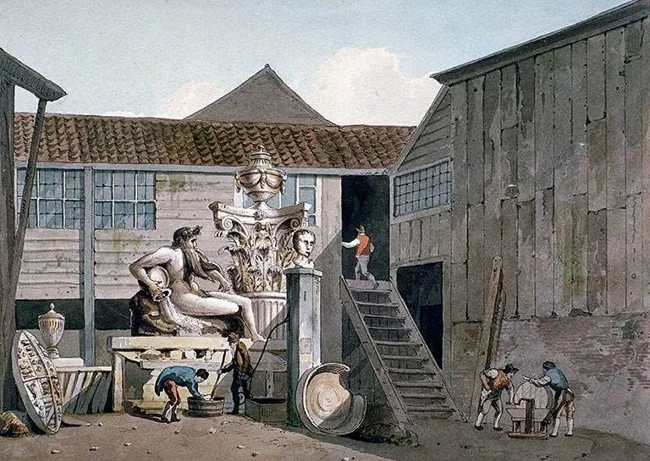

An engraving of the factory yard, London, circa 1800

Together they founded the Coade Artificial Stone Factory on the south bank of the Thames. Within two years, Pincott was fired and Eleanor took over the business on her own.

Making Coade stone was a labor-intensive process:

First, a clay model was created, enlarged by 10% to compensate for shrinkage.

Then they made a collapsible plaster mold so that it could be easily removed.

The clay mass was carefully pressed into the mold by hand.

After hardening, the mold was removed and the workpiece was sent to the kiln for several days.

Firing was the most difficult stage and required constant temperature control all night.

If something went wrong, cracks appeared, deformation, the product was rejected. Eleanor was very strict about quality.

Coad stone became popular among the leading architects of its time.

The Coade Stone became the royal choice. Eleanor received a patent from George III, which became the pinnacle of her career.

There is a myth that the secret of the Coade Stone died with Eleanor. In fact, the recipe was widely known by the mid-19th century. It's just that neither Coade nor Pincot patented their invention.

As researcher Caroline Stanford writes:

There was no single formula for Coade stone. Each piece required a special approach. The secret lay in the skill of potters and kilns.

Elinor was not only a craftswoman, but also a smart marketer. She organized exhibitions, collaborated with the Royal Academy, and actively advertised the product in newspapers.

Her 1784 catalogue listed 788 designs available to order. Customers could choose a ready-made solution or order a unique piece to suit their project.

Eleanor Coade died in 1821, leaving most of her fortune to charitable schools. Production continued for another 20 years until Coade stone was supplanted by a new invention, Portland cement.

However, today, products made from it can still be seen all over Britain - from London to Brighton. The most famous example is the lion on Westminster Bridge. Its condition is amazing: for two centuries it has practically not suffered from time and weather.

Lion on Westminster Bridge, London

Many Coad stone pieces still bear the fingerprints of the craftsmen who created them. These traces of the hands of the past are a tangible reminder of how art was born.