A bright history and tragic death of the first female pilot Sophie Blanchard (8 photos)

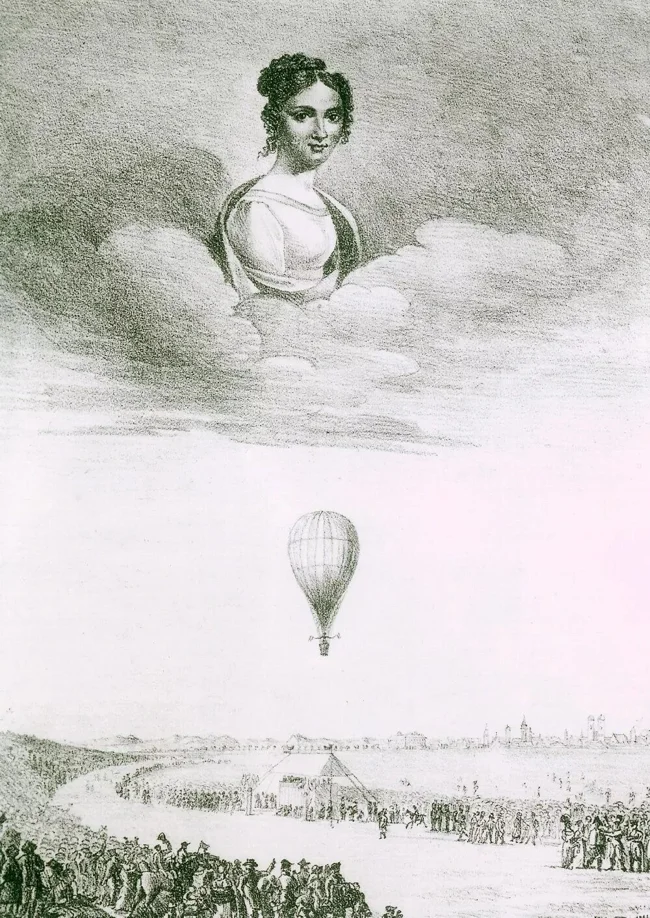

Ever since Sophie Blanchard took to the air with her husband, the famous aeronaut Jean-Pierre Blanchard, she knew she belonged to the air forever.

Until that moment, Sophie had been a shy and nervous young lady. She couldn't even take a ride in a carriage because even loud sounds would make her panic, leading her to hysteria. But once she took to the air, Sophie underwent an amazing metamorphosis and became a brave conqueror of the air. One day, this courage will cost her her life…

Sophie Blanchard

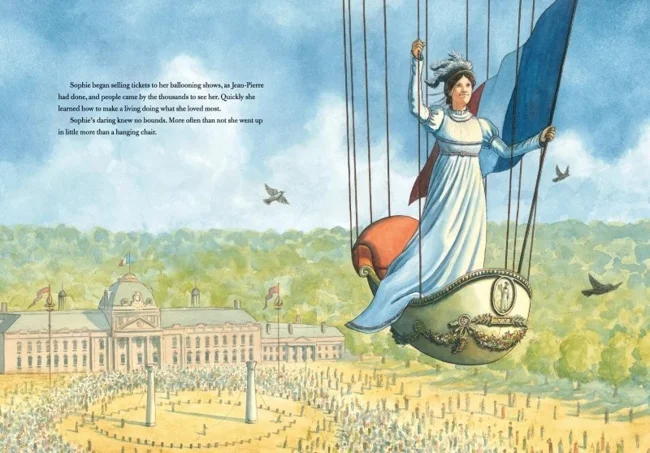

Sophie began flying with Jean-Pierre Blanchard in 1804. Her husband was a professional balloonist who made money from his skills. Blanchard would throw a dog tied to a parachute over the side of a hot air balloon, and once he even tried to jump with a parachute himself. But the earnings were not that great. Then Blanchard took Sophie with him, believing that the presence of a representative of the fair sex would arouse interest and attract attention. And he was right. Soon Sophie began flying alone, becoming the first female hot air balloon pilot.

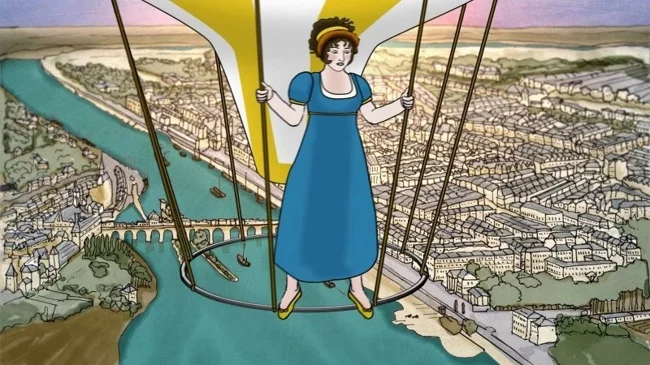

In 1809, Blanchard suffered a heart attack while flying over The Hague. He fell to his death. Deep in debt, Sophie continued to fly, gradually developing her own unique style. She often flew at night, sometimes staying in the air all night. While her husband parachuted dogs, Sophie added personality to her shows by launching fireworks from the sky.

Sophie became a favorite of Napoleon, who made her "Aeronaut of the Official Celebrations," which meant that Sophie was now responsible for organizing the aeronautical shows at all royal events. She made ascents in honor of Napoleon's wedding to Marie-Louise of Austria. On the birthday of Napoleon's son, Sophie flew in a hot air balloon over Paris and dropped leaflets announcing the birth of the child.

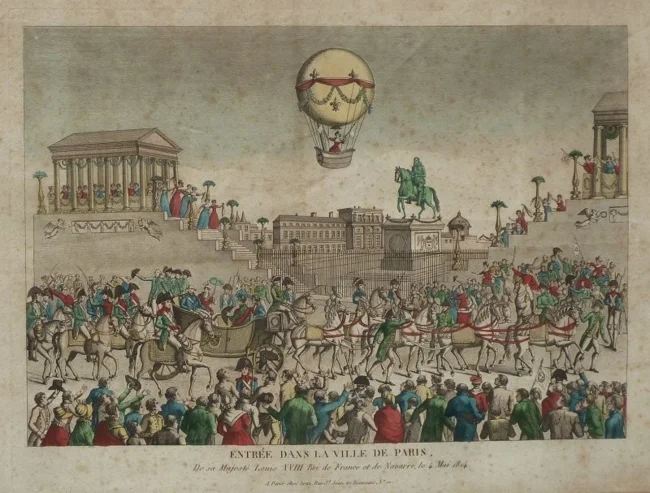

After Napoleon was defeated and Louis XVIII ascended to the throne in 1814, Sophie took to the skies for the new king and was given the title of "Official Aeronaut of the Restoration" by the impressionable ruler. Sophie's flights drew huge crowds across Europe, distracting people from other social events. One of her stunts involved climbing to enormous heights of over 3.5 kilometers, where she risked losing consciousness from the cold. Once, while flying near Vincennes, hail forced the woman into the air and she lost consciousness. When she finally came down, she had been in the air for over 14 hours. During the journey to Turin, the temperature dropped so much that frost formed on the woman's hands and face. The poor woman almost drowned in Nantes when she landed in a swamp by mistake. She would have certainly died if help had not arrived.

Unlike her fellow Montgolfier brothers, who flew in hot air balloons, Sophie and her husband Jean-Pierre Blanchard pioneered hydrogen balloon flights. The hydrogen balloon used hydrogen gas to provide lift; the gas was lighter than air. Although it was associated with a fire risk - hydrogen is highly flammable - using a hydrogen balloon saved Sophie from having to light a fire to keep the craft aloft. Hydrogen balloons were also smaller and easier to inflate.

On July 6, 1819, Sophie was preparing to ascend in front of a spectacle-hungry audience in the Tivoli Gardens in Paris. During her entire stay in Paris, she had been putting on two shows a week. But this show was to be especially impressive, as she was performing her trick with the "Bengal fire" - a slow-burning and extremely dangerous pyrotechnic show. Some spectators begged her not to ascend. And Sophie herself apparently had some doubts, since, according to eyewitnesses, she was nervous before the performance. But she finally decided to do it and promised that "this will be the last time."

Almost immediately after the balloon left the ground, a strong wind blew it toward the trees, and the balloon struck their tops. The impact dislodged the fireworks attached to the balloon, and the fire began to move toward the balloon, not away from it. Within moments, the structure was engulfed in flames, and it continued to move away.

Some spectators applauded, thinking the fireball was part of the show. But it soon became obvious that Sophie was in danger. The balloon began to fall rapidly, and Sophie dropped some of the ballast to slow it down. She had almost reached the ground when the balloon hit the roof of a house and tilted, throwing her out of her seat. By the time rescuers arrived, Sophie had already died - the unfortunate woman had broken her neck.

Sophie's Death

Sophie's death was mourned throughout Europe. Her story was retold by Jules Verne in his novel Five Weeks in a Balloon. For some, Sophie's death became an instructive example of behavior unworthy of a woman. Even Charles Dickens noted that "the pitcher often goes to the well, but is always broken at last."

Sophie's Grave

Sophie was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. A memorial depicting a hot air balloon engulfed in flames was erected above her grave. The epitaph on her tombstone reads "victime de son art et de son intrépidité" ("victim of her art and intrepidity").