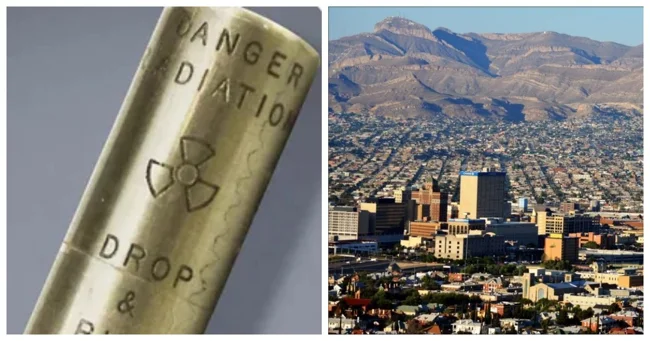

A frightening radiological incident in Ciudad Juarez (7 photos)

One of the worst radiation accidents in North America occurred in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, in 1984. Although not widely known, the incident has been called “100 times more intense” than the Three Mile Island accident in 1979.

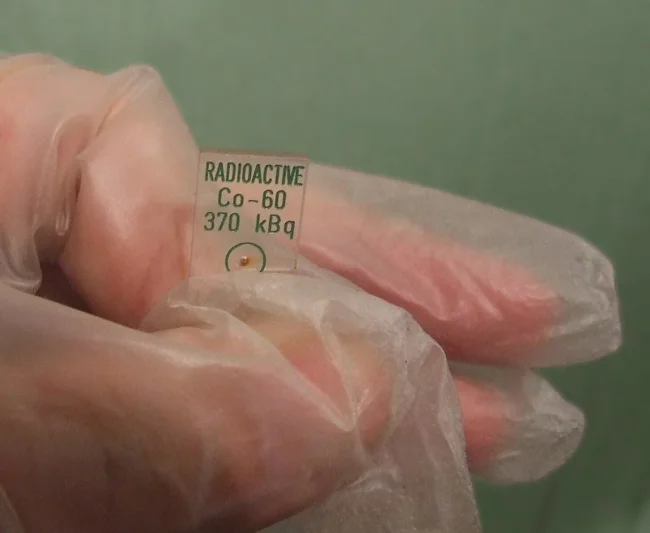

It all started in 1983 when Vicente Sotelo, a technician working at a city hospital, went into a general storage area to pick up some supplies. The hospital rented space in the storage area and used it to store unused equipment and other items. Among the items Sotelo took that day was a cylinder containing highly radioactive cobalt-60 in the form of small pellets. The cylinder was part of a radiotherapy machine the hospital had purchased six years earlier but never used.

Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

The hospital failed to notify regulators of the purchase, as required by law. It also failed to maintain the machine. Sotelo, unaware of the nature of the metal cylinder, loaded the radiotherapy machine into a pickup truck and drove to a junkyard, intending to sell it. Before arriving, however, he attempted to disassemble the cylinder, causing radioactive pellets to spill across the truck.

After returning, the pickup truck broke down and sat in a parking lot near the house for a month and a half. After this time, the truck was moved to another street, where it stood for another 10 days.

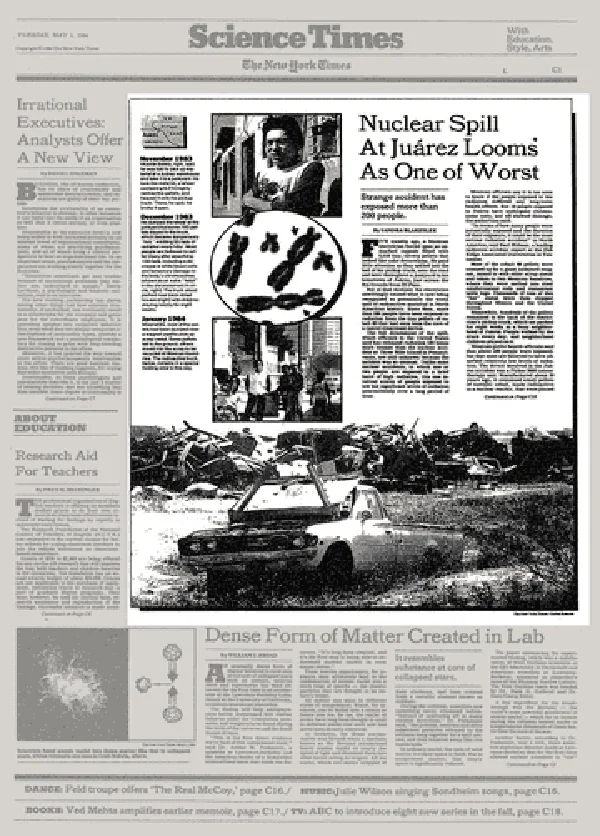

When cranes moved the cylinder along with other pieces of metal, cobalt-60 granules flew all over the dump, mixing with other metals. This radioactive scrap was sent to two foundries, where it was melted down and made from contaminated material rebar for construction and metal table frames. By January 1984, less than a month after the incident, the materials were being exported to the United States and parts of Mexico.

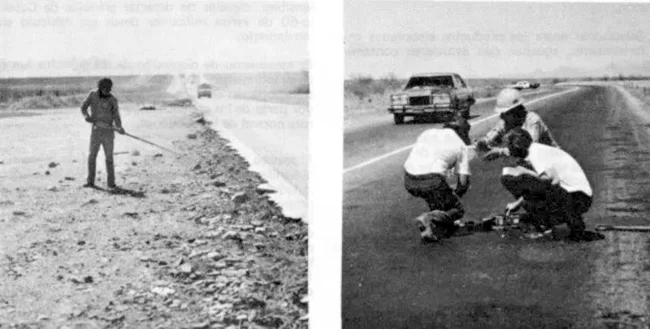

On January 16, a truck carrying rebar accidentally drove near the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, causing a sharp spike in the lab's radiation detector. After investigating, authorities realized that the cargo was the source of the radiation. Mexico's National Nuclear Safety and Safeguards Commission (CNSNS) was notified, confirmed that there had been a radioactive leak, and ordered foundries to stop shipping the rebar they had manufactured. The dump was also closed.

That same dump

When CNSNS scanned Sotelo's abandoned car, it was found to be emitting deadly radiation at up to 1,000 roentgens per hour – fatal to humans. It remained parked next to two houses, and children regularly played on it. Further investigation revealed that in addition to the dump and two foundries, three other companies had received contaminated material. The material was used to make about 30,000 table frames and 6,600 tons of rebar.

Workers without any protection search for radioactive pellets

CNSNS was able to recover 2,360 tons of unused rebar. The rest had already been used in construction. Authorities have identified 17,000 buildings in which contaminated rebar was used, and have determined that about 800 structures will have to be torn down due to off-the-scale radiation levels. CNSNS was also able to recover all 30,000 contaminated frames, as well as about 90% of the 1,000 tons of contaminated rebar that was shipped to the United States. The fate of about 1,000 tons of contaminated rebar is still unknown.

The pickup truck carrying the cylinder

The accident was incredibly expensive for Mexico. However, the greatest losses were suffered by people who were directly exposed to radioactive cobalt. By some estimates, about 4,000 people were exposed to radiation, with about 80 people receiving doses over 25 rem. Of these, five people received doses between 300 and 700 rem over two months. Chronic doses over 20 rem increase the risk of developing cancer, and acute doses of 500 rem kill half of the victims without timely medical care. Fortunately, there were no deaths as a result of this incident.

Sotelo was fired from his job. The hospital claimed he had no right to dump the radiotherapy machine. Sotelo dismissed the accusations. "We're still alive," he said in an interview. "Maybe the doctors just exaggerated the danger."