La Catedral: Pablo Escobar's personal prison (11 photos + 1 video)

By 1991, Pablo Escobar had made an astonishing journey from car thief, small-time trafficker, and kidnapper to the title of Kingpin of the Underworld.

But this transformation came at a high price. Over the course of a decade, Escobar had amassed countless enemies, including rival drug cartels and governments. Their combined efforts gradually destroyed Pablo's life and empire. His battle with the Cali Cartel cost the lives of more than 300 of his associates and family members.

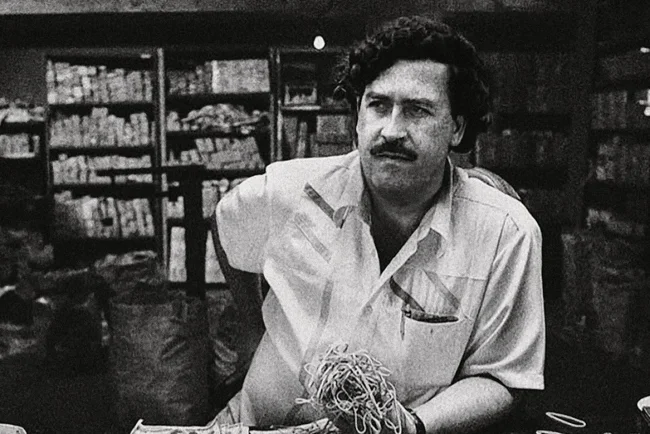

Pablo Escobar

Escobar also saw drug lords like Carlos Lehder extradited to the United States, while others like the Ochoa brothers surrendered and went to prison. Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha, another Colombian drug lord, and his son were killed in shootouts with police. The final straw was when his daughter Manuela was injured in an explosion at his residence.

Visitors and supplies were brought to La Catedral by truck, as seen in this image from a security camera inside the truck.

Escobar wanted to surrender, but he was afraid that the Colombian government would extradite him to the United States, the one thing he was terrified of. "Better a grave in Colombia than a cell in the United States," he said.

Escobar negotiated with the authorities and, after six months, agreed to go to prison. But not just any prison, but one built to his own order and in a location of his choosing. He would have his own personal guard, whose main duty would not be to prevent escape, but to protect him from enemies. Other conditions were put forward, including the removal from power of General Miguel Maza, one of Escobar's most ardent opponents. Another demand was that the Colombian National Police be prohibited from coming within 20 kilometers of the prison.

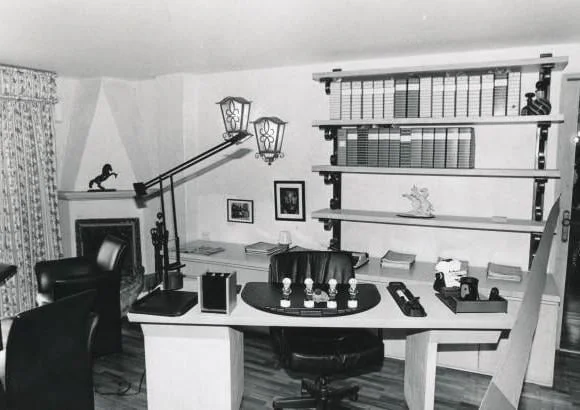

Prison interior

In exchange for these conditions, the government agreed not to extradite Escobar to the United States. Escobar's fake imprisonment may have been inconvenient for the country, but it would have helped the government get rid of an eternal global problem. The agreement also ended the money spent on the endless pursuit of the cartel leader.

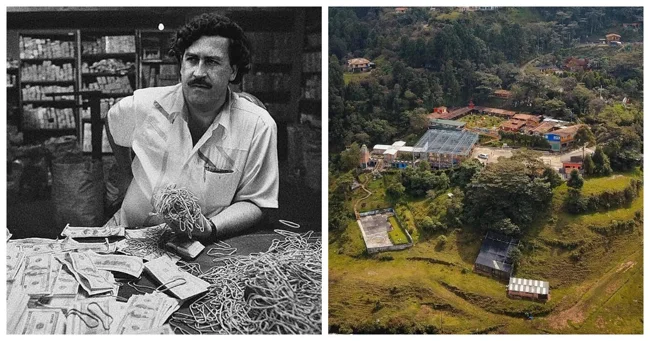

Before Escobar officially surrendered, he began construction of his prison in the hills overlooking the city of Medellin. The elevated location gave Escobar a bird's eye view of the city, which he effectively owned and ran for over 15 years. Escobar also appreciated the steep terrain.

Escobar surrendered to authorities on June 19, 1991. He was immediately transported by helicopter to the newly built "prison." The complex was named "La Catedral," or "The Cathedral," for its aesthetics, luxury, and comfort.

Some called it "Club Medellin" or "Hotel Escobar." La Catedral housed a soccer field and several buildings, including a cinderblock house for the warden, seven guard towers, and a large building for prisoners located higher up the hill. Escobar had his own suite with a rotating bed, a bathroom with a Jacuzzi, a dance floor, a bar, a gym, a pool room, and even a dollhouse for his daughter to play with when she came to visit.

He had cell phones, radios, and a fax machine that allowed him to run a business that, at its peak, was bringing in $60 million a day for his cartel and controlled up to 80% of the cocaine shipped to the United States. Pablo also had a powerful telescope that allowed him to look down on the city of Medellin. Escobar would talk to his daughter on his cell phone while simultaneously seeing her through the telescope. The entire complex was surrounded by a fence and electrified barbed wire.

During his imprisonment, Escobar would have a wide variety of people visiting him every week. Among them were friends, business partners, leading politicians, beauty queens, and elite prostitutes. Parties were common. For his 42nd birthday, the king hired Medellin's best chefs and threw a lavish banquet. He even held a wedding in his prison.

Escobar regularly invited football players to play in prison. Before the 1994 World Cup qualifiers, all twenty-two players from the Colombian national team visited La Catedral and took part in a friendly match against one of the most famous football clubs in the world. Prison guards served drinks on the sidelines and later acted as waiters at the bar.

Escobar could do whatever he wanted, but when he ordered four of his lieutenants to be tortured and killed during a dispute over money, the government decided that things had gone too far and decided to transfer Escobar to a real prison.

On July 22, 1992, a year and a month after Escobar moved into his prison, Deputy Justice Minister Eduardo Mendoza went to meet with the prisoner to inform the cartel boss of the change. Escobar was furious and threatened to kill Mendoza. When news of Mendoza being held hostage reached the authorities, the Colombian National Army surrounded the prison and a shootout broke out between soldiers and Escobar's guards. In the confusion, Escobar managed to escape through an emergency exit he had built into the prison during its construction.

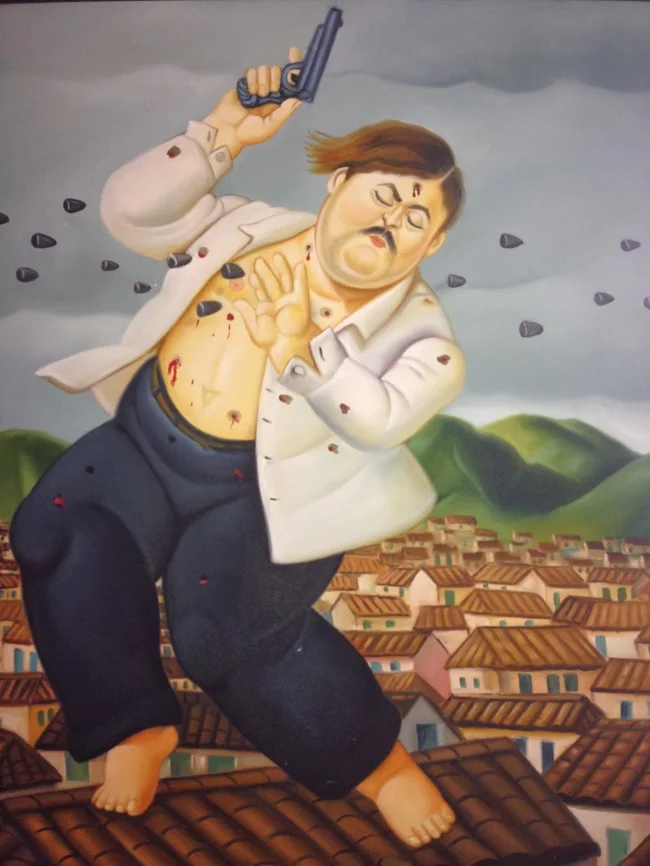

Painting "The Death of Pablo Escobar" by Fernando Botero

The Colombian government launched a massive manhunt for the criminal. Despite thousands of soldiers and police combing the streets of Medellin, Escobar managed to escape justice for seventeen months, until December 2, 1993, when authorities caught up with him. The drug lord was shot dead while trying to escape.

La Catedral sat abandoned for years. Scrap hunters stripped it of anything of value, including bathtubs, pipes, tiles, and roofing materials. During his time at La Catedral, Escobar smuggled cash into prison in milk cans. Rumors swirled that the complex still contained millions of dollars in cans, which attracted treasure hunters who turned everything upside down in hopes of finding the rest of Escobar's fortune. Nothing was reportedly found.

The former prison today

In 2007, the Colombian government gave the 28,000 square meter site to a brotherhood of Benedictine monks, who turned it into a “religious and cultural tourism center,” which now includes a chapel, library, cafeteria, guesthouse for religious pilgrims, workshops, a nature trail, and a memorial dedicated to cartel victims.

The campus also houses a shelter for seniors who cannot afford long-term care in the city.

A giant mural of Escobar behind bars hangs on the original concrete wall supporting one of the new senior housing buildings. It reads, "Those who don't know their history are doomed to repeat it."