The unrivaled balance of Logan Rock: who and why tried to test and shake it? (8 photos)

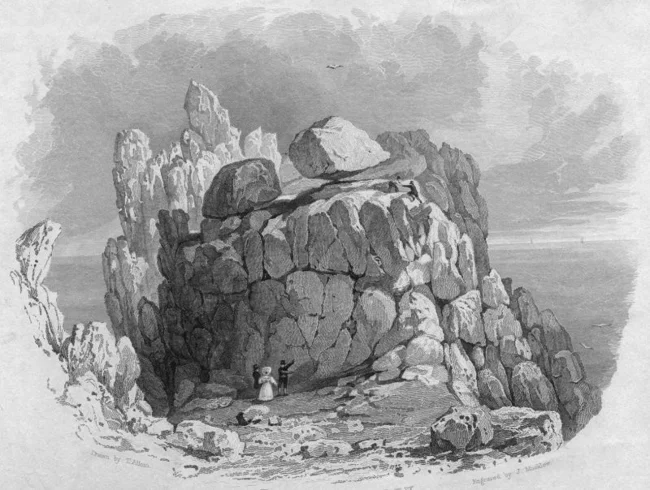

On the edge of a cliff overlooking the English Channel, on a headland a mile south of the village of Treen in Cornwall, England, sits the famous Rocking Stone. Despite weighing 80 tons, the rock is so well balanced at its base that even a child can rock it back and forth with just a little pressure.

Known as Logan Rock – from the Cornish word logging, meaning rocking – it is one of several similar balancing stones found in the county.

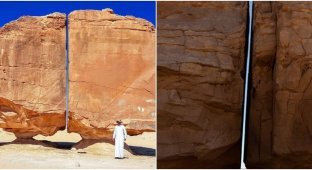

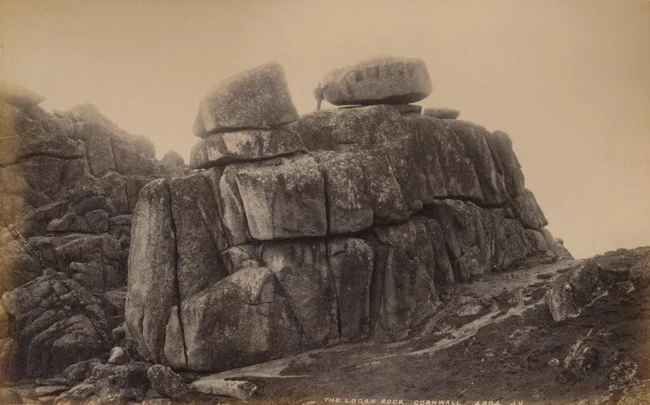

Logan Rock (top right) on the headland

Rocking stones were once thought to be man-made, associated with Druidic rituals and religious ceremonies. Legend had it that a rocking stone could be used to determine a person's guilt or innocence. The stone was thought to rock at the slightest touch of the pure in heart, but would withstand the force of even a giant if the guilty acted upon it. As William Mason wrote in his dramatic poem Caractacus, "It moves docilely at the slightest touch of him whose bosom is pure; but to a traitor, though the valour of a giant irritate his hand, it stands as firm as Snowdon (the highest mountain of Ulls)."

Close-up of the rock

The rock was also described by Dr William Borlase, a Cornish antiquary, geologist and naturalist, in his 1754 book, The Antiquities of Cornwall:

In the parish of St Levan is a headland called Treryn Castle. This headland consists of three distinct groups of rocks. On the western side of the middle group, not far from the summit, lies a very large stone, so level that any hand could move it from its place; but the points of its base are so far apart, and so well secured by the proximity of the stone on which it rests, that it is impossible that any lever or force, however mechanically applied, could move it from its present position.

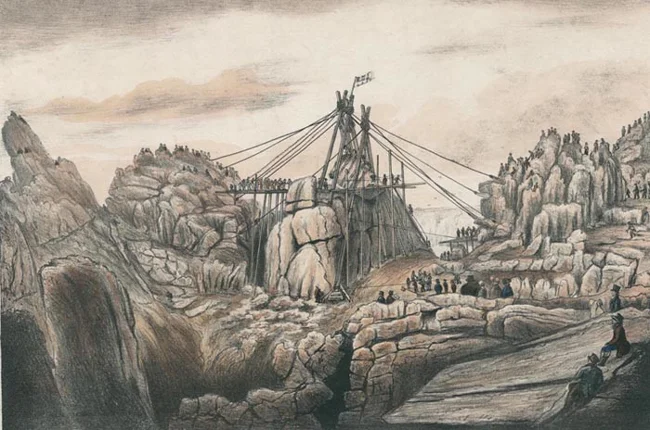

A 19th-century engraving of Logan Rock

Although the rock is well known locally, it has become much more famous throughout Britain and even the world through the actions of one man. That man was Lieutenant Hugh Goldsmith, nephew of the poet Oliver Goldsmith.

In 1824, Goldsmith arrived in Cornwall on the six-gun cutter HMS Nimble and, having heard about the legend of Logan Rock, decided to test the theory of its immobility. Well, or disprove it. Goldsmith took nine men with him and, using three hand pikes, tried to move the stone from the cliff. When the attempt was unsuccessful, the men set to work, swinging the stone with such force that Goldsmith was worried that the boulder would fall on them. The order to stop work came too late, and the stone broke loose and rolled several meters. Fortunately, it did not fall into the sea, where it could have disappeared forever, but into a narrow crevice.

Once news of Goldsmith's folly reached the townspeople, it caused an avalanche of indignation. Logan Rock was a popular tourist attraction, with many families making their living from the landmark. A local politician named Sir Richard Vivian vowed to "pursue the offender with all possible vigor," and the townspeople pressured the British Admiralty to strip Lieutenant Goldsmith of his commission in the Royal Navy unless he returned the boulder to its original location at his own expense.

Shocked by the backlash he had provoked, a remorseful Goldsmith wrote to his mother in a letter dated 24 April. He wrote: "I did not know that this stone was so much worshipped in this district, and you can imagine my astonishment when I found all Penzance in disorder; the newspapers had slandered me and made me out to be worse than a murderer, and the baseness of their lies was more than impious."

Fortunately, Goldsmith found support from the famous engineer and politician Davis Gilbert, who persuaded the Admiralty to provide the equipment free of charge, and also donated £25 himself to set the stone in place. Goldsmith was to cover the costs of labor and other expenses, which in total amounted to £130. This was an impressive sum at that time, especially for a man of modest means.

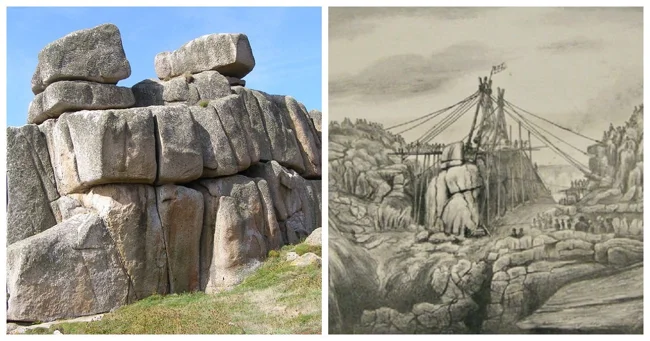

Climbing Logan Rock to the Cliff

After months of preparation, work finally began on 29 October 1824, and on the afternoon of 2 November, in front of thousands of spectators and with the help of over sixty people, the Logan Rock was carefully lifted back onto the cliff and set in its original position. However, it was noticed that the stone no longer swung as easily as before. Cornish historian Craig Weatherhill claimed that a series of rhythmic blows on the south-west corner would cause the stone to begin to move, after which it could be maintained with the effort of one hand.

Three anchor holes drilled into granite near Logan Rock

For some time after this, the rock was kept in place with chains and padlocks to prevent the beloved landmark from being lost again. But eventually these restrictions were lifted and the rock was released from insurance. The anchor holes used to return the huge stone to its place are still visible in the surrounding cliffs.

Goldsmith repaid the debt with interest shortly before his death. In 1809, he was promoted to lieutenant, but he went no further. He continued to command small ships until his death at sea in 1841.