Francesca Rojas: The First Crime Solved Using Fingerprinting (8 photos)

Nowadays, it seems expected and obvious when a brilliant detective collects evidence at a crime scene, among which there will certainly be fingerprints. Often, they help to find the criminal. But, of course, the fingerprinting method was not always used. And this case is considered the first.

On June 29, 1892, in the town of Necochea, located in the southeast of Argentina in the province of Buenos Aires, two small children were found brutally murdered in their home. The victims were six-year-old Ponciano Carballo Rojas and his four-year-old sister Felisa. The children's throats were slit. Their mother, Francesca Rojas, was also stabbed in the neck. The wounds were superficial, and Francesca survived the attack.

Necochea today

The woman claimed that their neighbor Ramon Velasquez was responsible for the attack, killing her children because she rejected his advances. She later changed her story, saying that Velasquez was trying to take the children away from her at the behest of her husband, who was planning to leave her. Whatever the truth, Ramon Velasquez was arrested on suspicion of murder.

Velazquez was interrogated by the police and even tortured, but he categorically denied that he had killed the children. According to one version, Velazquez was forced to spend the night in a cell with the children's bodies, in an attempt to exert psychological pressure and extract a confession in such a terrible way. However, the man claimed that he was innocent and stuck to his version that he was with his friends at the time of the murder. He even had an alibi that confirmed his words.

The local police asked for help from the police in the provincial capital, La Plata, and Inspector Eduardo Alvarez was sent to Necochea to conduct further investigation.

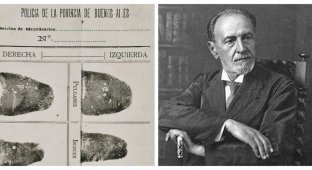

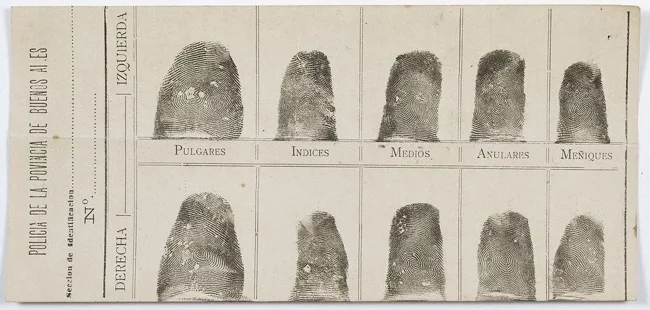

Francesca Rojas's Fingerprints

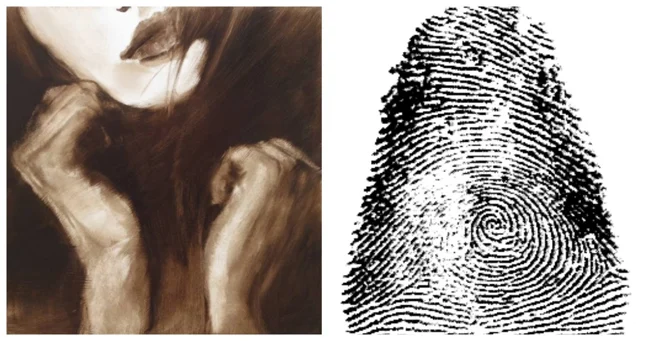

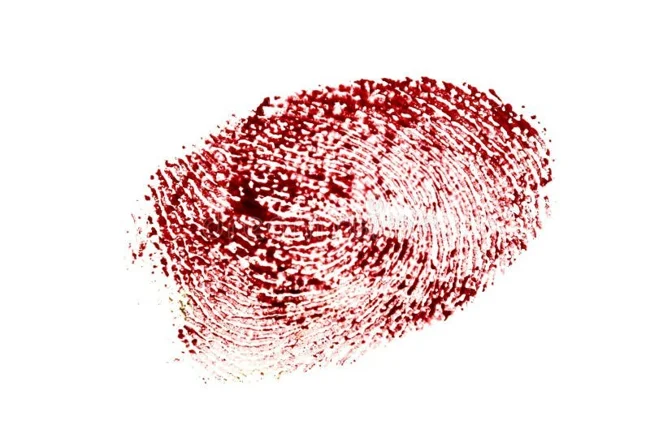

After examining the crime scene, Alvarez found a bloody fingerprint on the door to the children's bedroom where the attack and murder had taken place. He asked for the piece of wood with the fingerprint to be confiscated. He also took the fingerprints of Velasquez and Francesca using ink on paper and sent them, along with the piece of wood, to La Plata for examination.

At the time, the use of fingerprints to solve crimes was in its infancy.

Instead, fingerprints were used primarily for identification. In ancient China, around 220 BCE, fingerprints were used to authenticate government documents. These documents, usually made of bamboo slips or pages, were rolled up and tied with string, sealed with clay. The author's name was imprinted on one side of the seal, usually in the form of a stamp, and a fingerprint was imprinted on the other. With the invention of paper in the 2nd century, signing documents with fingerprints became common practice in China, and later spread to India.

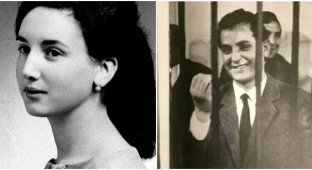

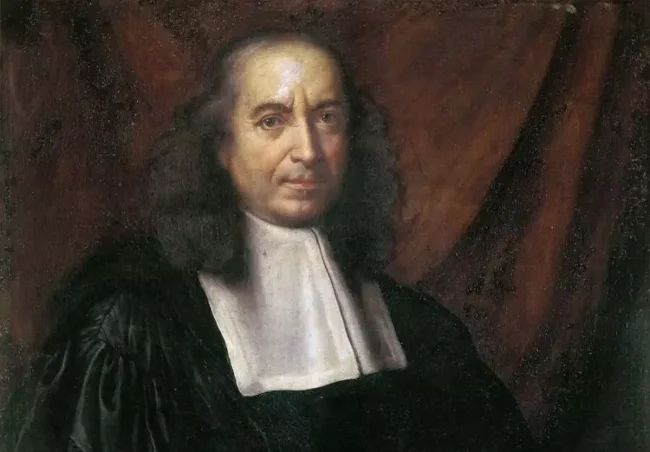

Italian biologist and physician Marcello Malpighi

European scientists began to seriously study fingerprints in the late 16th century. In 1686, Marcello Malpighi, a professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna, identified ridges, spirals, and loops in fingerprints. Then, in 1788, German anatomist Johann Christoph Andreas Mayer became the first European to conclude that fingerprints are unique to each person.

By 1892, the police department of the Argentine city of La Plata had created the world's first working fingerprint database, created by anthropologist and mathematician Juan Vucetich.

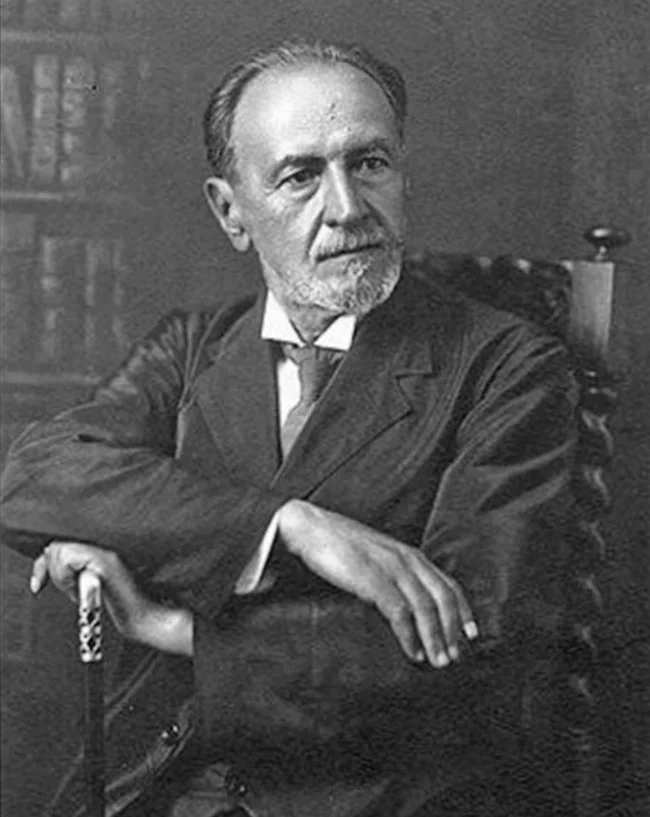

Anthropologist and criminologist Juan Vucetich

Horvath Vucetich worked as a statistician at the Central Police Department of La Plata until he was appointed head of the anthropometric identification bureau. Inspired by the ideas of Francis Galton, Vucetich began experimenting with fingerprints in 1891. He began collecting fingerprints of criminals and developed his own classification system. The Vuchetich classification system and the individualization of prisoners using fingerprints were the first practical applications of fingerprint science by law enforcement officers.

When analysts trained by Vucetich analyzed fingerprint samples sent by Inspector Eduardo Alvarez of La Plata, they discovered that the fingerprint on the door frame matched that of Francesca Rojas. After being confronted with this evidence, Francesca confessed to the murders of her two children and admitted to inflicting the injuries on herself in an attempt to increase her chances of marrying her lover, who did not like children. Francesca was subsequently found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

The case confirmed Vucetich's faith in fingerprints, and in 1903 Argentina became the first country to rely solely on fingerprints as a method of identification. The Rojas case inspired other countries to introduce fingerprinting into forensic science, leading to a flurry of convictions that would not have been possible without fingerprints. One of the earliest such cases occurred in 1898 in the Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal, India.

A tea garden manager was found lying on his bed with his throat slit, and several hundred rupees were missing from his mailbox and safe. Initially, suspicion fell on one of the coolies, the farmhands who worked in the garden, as the deceased had a reputation for being a harsh employer. The culprit could have been his cook, who had blood stains on his clothes. Suspicion also fell on the relatives of the woman with whom the deceased had had an affair.

In addition, suspicion fell on a roving gang of Kabulis who had recently camped in the area. Among the suspects was a former servant whom he had imprisoned for theft. However, during the investigation, the police came to the conclusion that there was insufficient evidence to charge the coolies, the woman's relatives, or the Kabulis. The former servant had been released from prison a few weeks earlier and had not been seen in the area since. Several blood stains were found on the cook's clothes, but these were explained by the fact that it was a pigeon which he had been gutting for his master's dinner.

In the mailbox, the police found a diary with two very faint brown stains on the outside cover.

Upon closer inspection with a magnifying glass, it was discovered that they were fingerprints. The Bengal police kept a database of fingerprints of all people convicted of certain crimes, and when compared, the prints on the diary matched those of the former servant. As a result, he was arrested and brought to Calcutta for trial. However, he was only found guilty of theft, as there was not enough evidence for murder.

The idea of using fingerprints to catch criminals eventually found its way into fiction. Mark Twain's 1893 novel Pudd'nhead Wilson features a courtroom drama in which a murder mystery is solved through fingerprint identification. Similarly, in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's 1903 short story The Norwood Builder, the famous detective Sherlock Holmes solves a murder and unmasks the culprit through bloody fingerprints.

The development and use of fingerprinting as a criminal investigation tool has revolutionized law enforcement practices around the world. From its early days as an identification method to its key role in solving crimes described in literature, fingerprinting continues to be a cornerstone of forensic science.