Dönitz's "dishonorable" submarine war. "Wolf packs" in the service of the Kriegsmarine (7 photos)

Already in the First World War, German submarines established themselves as an excellent means of combating transport, causing significant damage to enemy maritime trade. Therefore, by the middle of the war, the British Admiralty changed its shipping tactics: single ships disappeared, and all transport began to move in convoys under the protection of anti-submarine ships.

The Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, Grand Admiral Dönitz, gives a speech to the Kriegsmarine personnel. In his hand is one of the two grand admiral's wands made for the admiral.

This tactic quickly bore fruit, and after British sloops sank several German submarines, the captains of the latter were afraid to attack the convoys. They were forced to look for single targets, and if there were none, to attack the convoy from the maximum possible distance, having a slim chance of destroying at least one ship.

Even during his years of service on the submarine UC-25, the young Lieutenant Karl Dönitz proposed to the command to use tactics in which several submarines act together. He argued that a simultaneous attack by several submarines scatters the attention of the convoy forces, thereby increasing the likelihood of hitting targets several times. Dönitz failed to achieve the implementation of his ideas, although they were actively supported by the commander of the submarine forces, Hermann Bauer, whom a number of historians consider the real father of the “wolf pack” tactics. In one of the raids, Dönitz's submarine was severely damaged by anti-aircraft ships guarding the convoy and was forced to surface, after which the entire crew, including Dönitz himself, was captured.

Creation and development of “wolf pack” tactics

After the war, Dönitz returned to Germany from British captivity and was reinstated into the Navy in 1919. During his service, he did not abandon his ideas, continuing to improve tactics for fighting convoys, which he called Rudeltaktik, or “group tactics.” The efforts of the young and promising officer were appreciated only after the Nazis came to power. The then frigate captain Karl Dönitz, commander of the cruiser Emden, was promoted and given command of the newly formed 1st Kriegsmarine submarine flotilla Weddingen.

In his post, Dönitz developed a vigorous activity - he finally formalized the theoretical part of his revolutionary tactics, and also directed all his activity towards achieving an increase in the production of submarines.

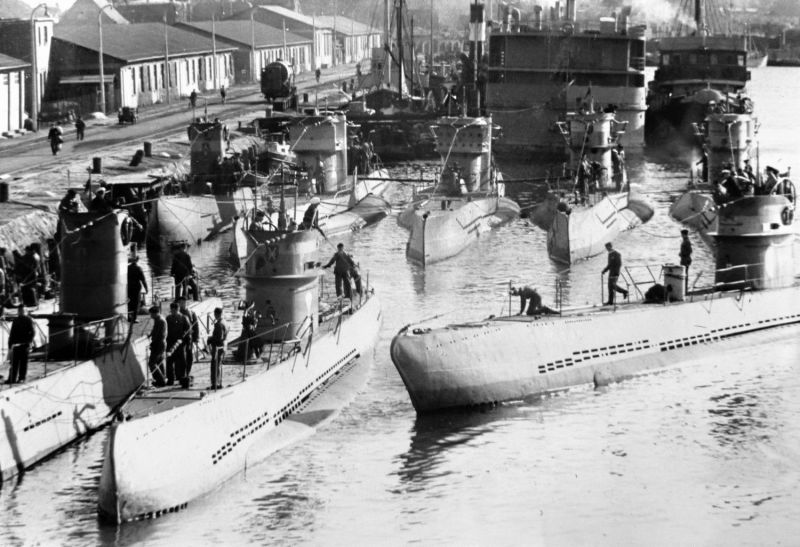

German submarines II and VII series of the 1st U-boat training division (1. Unterseebootslehrdivision) at the pier in Pillau

In his opinion, in an open confrontation, the Kriegsmarine forces could not oppose anything to the British. Britain could field 15 battleships and battlecruisers for 4 German battleships, and 5 more were being completed. The Royal Navy also had 7 aircraft carriers, which the Germans did not have at all. Therefore, Dönitz insisted on an all-out submarine war: it seemed more rational to mass produce submarines that could paralyze the supply of the mother country and seriously limit the actions of the British linear forces with surprise attacks.

Nevertheless, the General Staff ignored his arguments. Commander Raeder lobbied the Fuhrer for the construction of battleships, cruisers and aircraft carriers. Therefore, by the beginning of the war, the Kriegsmarine submarine fleet consisted of only 57 submarines, mostly belonging to the II series. Boats of this series were intended exclusively for operations in coastal waters.

The beginning of the submarine war

At the outbreak of war, the British Admiralty required that all supplies be carried out by convoy. The memories of the damage German submarines caused to maritime trade during the First World War were still too fresh. And under the command of Dönitz, German submariners again became a serious threat to British trade communications: in just 4 months of 1939, they sank more than 110 ships with a total tonnage of 451,000 tons, losing only 9 submarines.

Moreover, all submarines operated according to the previous pattern of individual hunting. First, the target was tracked, after which it was attacked at the appropriate moment. The German submariners owed this success to the British themselves - the proud islanders considered submarine warfare dishonorable and did not properly train the crews to fight submarines. This allowed submarine captains to make daring attacks on Allied ships. And yet, gradually the anti-aircraft defense measures were strengthened, the work with the hydrophone was improved, and it became more difficult to attack convoys alone.

Exercises of German submarines of the 1st submarine training division (1. Unterseebootslehrdivision) in Pillau. The picture shows submarines of the VII series and II series

Back in 1939, Dönitz “pushed through” Roeder and received permission to conduct an operation based on his Rudeltaktik tactics. The operation was unsuccessful due to lack of coordination. It, like a group of 6 submarines, was led by one of the captains who failed to correctly assess the situation. In addition, out of six U-bots, only four reached the place, and another one died during the attack on the convoy. The remaining three U-bots accounted for 3 large vessels with a total displacement of 24,467 gross register tons. (for comparison, the displacement of the Titanic was just over 52 thousand tons). The operation was considered unsuccessful.

First successes

Despite the first failure, Dönitz continued to develop his idea. He believed that entrusting command to an officer on the spot was a mistake; actions should be coordinated only from headquarters.

By the beginning of 1940, submarines of the VII-B and VII-C types began to enter service, possessing high speed, autonomy and a reserve of 14 torpedoes. Therefore, in the middle of the same year, by order of Dönitz, two groups “Rösig” and “Prin” were formed for operations in the North Atlantic. They did not achieve impressive successes, but there were no losses, which allowed the commander of the Kriegsmarine submarine fleet to get the go-ahead to continue using Rudeltaktik tactics.

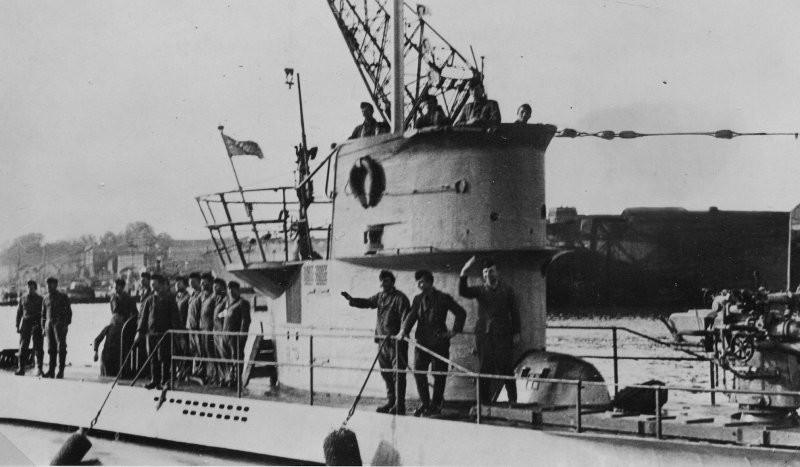

The submarine U-99, whose permanent commander was Lieutenant Commander Otto Kretschmer, was the most successful submariner of the Second World War. When attacking convoy SC-7, U-99 sank the most ships - 9 ships

October 17, 1940 became the “finest hour” for German submariners, and the Allies called it “the night of the long knives.” The submarine U-48 discovered the British convoy SC-7 and radioed to headquarters. By order of Dönitz, submarines began to approach the convoy, which continuously attacked it throughout October 17 and 18. As a result, 20 ships with a total tonnage of almost 80 thousand gross tons went to the bottom.

Some of the boats, having fired their ammunition, returned to the port immediately after the attack, the rest continued to patrol. On October 20, another convoy, HX-79, was discovered with fewer ships. The result of the meeting was 12 sunk ships with a total tonnage of 75,000 gross tons. There could have been more, but the submarines ran out of torpedoes.

Thanks to this success, Dönitz received carte blanche. Despite the fact that the linear forces of the Kriegsmarine were clearly losing, especially after the death of the Bismarck and the failure of the Prinz Eugen in May 1941. After which the Fuhrer forbade cruisers and battleships to operate on sea lanes. But Dönitz’s “wolf packs” received complete freedom of action. This is the name given to them by the British who suffered most from their actions.

Wolf pack tactics

By order of the command, submarines (from 2 to several dozen) were united into an operational formation with direct subordination to the headquarters of the submarine forces. The group was given its own name, and it operated for a certain time. For example, one of the most effective groups, called Eisteufel, operated in the Arctic from 06/21/1941 to 07/12/1941 against the notorious convoy PQ-17.

Ships of the cruising formation from the covering forces of convoy PQ-17 before the convoy sets out on a voyage. From bottom to top: heavy cruiser HMS Norfolk, aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, to the right the flagship of the formation, heavy cruiser HMS London. American ships in the background

After leaving the port, each submarine went to its own square for combat duty, creating a kind of curtain on the possible route of convoys. This greatly increased the likelihood of detecting enemy ships and vessels.

Having discovered the convoy, the submarine radioed to headquarters and followed it, being out of sight and guided by smoke. The rest of the boats from the “flock” moved at full speed towards the indicated coordinates and entered the strike position. German submariners tried to attack at night from the surface in order to achieve higher hit accuracy.

Each commander chose targets at his own discretion, but since the attack came from different directions, panic arose in the convoy, and the escort ships could not quickly respond to threats and pursue the submarines. If necessary, the boats moved to a distant Type XIV supply submarine, which the submariners called a “cash cow.” On board there were up to 400 tons of fuel and 4 spare torpedoes, which, if necessary, could be reloaded onto a combat submarine in need of replenishment of ammunition.

Between 1940 and 1943, the Kriegsmarine submarine command used more than 250 “wolf packs” operating not only in the North Atlantic and Arctic, but even off the coast of South Africa and North America. The peak use of this tactic came in 1942, when the submarine fleet already included more than 350 ocean-class submarines capable of operating with higher autonomy. The submariners accounted for more than 2,700 ships, while their own losses amounted to 85 boats. German sailors of that time called this period “Happy Times” (July-October 1940) and “Second Happy Times” (January-August 1942).

German submarines U-251, U-255 and U-408 in Narvik harbor after a trip to convoy PQ-17, July 15, 1942

But by mid-1943 the situation had changed. In October 1942, the British captured a modernized version of the Enigma encryption machine and hacked the submariners' coded radio communication system. In May 1943, a new type of AS-G radar, operating in the centimeter range, and a DAR direction finder entered service with the Allies. PLO ships and aircraft began to be equipped with new devices, which made it possible to much better determine the location of a submarine, even if it was at depth.

The most important role was played by American industry, which by the end of 1942 was completely on a war footing. The American shipbuilding industry launched dozens of escort destroyers, corvettes and frigates every month for its own fleet, as well as for the allied fleet. These ships, organized into task forces and reinforced with escort aircraft carriers, staged a real hunt for German submarines in the Atlantic.

The Germans lost the Battle of the Atlantic. Despite the development of new materials that partially absorb radar radiation, the adoption of Project XXI boats, revolutionary for their time, new types of torpedoes and the new doctrine of “unlimited submarine warfare.” However, from 1944, wolf pack tactics again became popular, but this time among American submariners faced with the strengthening of Japanese convoys. But the Americans did not have such “happy times” as the Kriegsmarine sailors...