How it was. Part 19. Daggers with a curved blade (23 photos)

I present to you a small selection of armor and weapons. I warn the lazy people at once there are not just a lot of letters, but a lot. For aesthetes, I want to add - it has not been read or verified.

Daggers with curved blades are primarily characteristic of the East and are little known to the West. Appearing to Western European culture, including weapons culture, as something outlandish. Although the kopis of the ancient Persians and then the Greeks had such curved blades, and now they have jambia or ganjir - a curved Indian dagger with a reverse sharpening blade (scimitar type).

In terms of the curve of its blade, the eastern dagger is an imitation of a cow's horn, only in a flat form (there are, however, also round ones) and made of steel. This makes us think that the primitive dagger was nothing more than a real horn - an assumption further supported by the fact that deer antlers trimmed in the form of a dagger were found in deposits of the Paleolithic era (in France). Horns served as weapons in later eras; Thus, in India, until recently, a weapon made of two sharp horns, connected by their bases and covered in this place with a round metal plaque to protect the hand, was used. This weapon was used in hand-to-hand combat, to strike left and right. The steel analogue of this weapon is the bichwa - two ganjir daggers on one handle.

The variety of curved daggers is enormous. And there is simply no way to describe them all. True, in most cases they all had a triangular or leaf-shaped blade. Nevertheless, original daggers were also found in Asia, and, therefore, from the point of view of a European, very exotic. But let's start with curved daggers of simple shape.

Until our time, jambias with a wide, double-edged curved blade are extremely popular among Arabs. Apparently the most advanced type of dagger, the jambia combines truly lethal efficiency with what is now called an "intuitive interface." The technique of striking with it is extremely simple. The sharpness and very large bend of the jambia blade allows you to inflict cut wounds with natural wide strokes, similar to how it is done with a curved Turkish saber.

When stabbing from bottom to top (and with a reverse grip and from top to bottom), the tip of the blade is oriented exactly in the direction of the natural circular movement of the hand, which provides high penetrating force. Well, and if the jambia is pierced, in the wound the upper concave edge of the dagger begins to act like the sickle of a scimitar. The “naturalness” of the blows delivered by the jambia creates the conditions for a uniform, extremely strong position of the fingers on the handle. The wide base of the blade completely covers the hand, allowing you to do without a guard. Finally, the short (no more than 25 centimeters) length of the dagger blade allows you to freely use it in a dump.

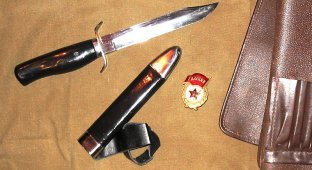

Bebut is one of the main (along with kama) types of Caucasian daggers, with a curved, double-edged blade up to 50 cm long, most often with fullers. Its historical roots most likely lead to Persia, but it has taken root in the Caucasus. Bebut also became popular among the Cossacks. And in 1907, the bebut, specially designed as a replacement for the saber, was adopted into service in Russia. It was in service with the lower ranks (soldiers and non-commissioned officers) machine gunners, artillerymen, reconnaissance officers, crews of armored trains, etc.

The Russian bebut of the 1907 model had a polished steel blade with two narrow fullers on each side. Material - carbon steel. The handle is made of two wooden dies. The dies are secured with two large brass “buttons”. The top one also holds a rough brass bushing. The cross-section of the handle in the middle part is a square with slightly convex sides and rounded corners. Balance of a dagger for chopping: the center of gravity on the blade in the area where the fuller begins. The slight curvature of the blade and the angle of the blade tip are quite suitable for stabbing. The symmetrical handle and double-edged blade simply provoke a variety of forward and reverse grips with both a convex and concave part forward. Both secant and force cutting actions do not cause inconvenience. The length and weight of the bebut is quite enough for confident cutting. The weapon is quite versatile, controllable and convenient. But it would be difficult to use a bebut from a horse against a foot adversary, or vice versa from the ground against an attacking cavalryman: it is a bit short with its 40-45 cm blade. The total length of the bebut of the 1907 model is up to 600 mm, blade length is about 440 mm, blade width is 35 mm, weight is up to 750 g.

But there were also rare, exotic weapons, closely associated with a particular place or era. A serpentine “flaming” blade, widening towards the base and turning into a guard, a “pistol” handle bent downwards... Can you imagine anything more unusual than the Malayan kris? It seems as if its creators decided to achieve originality at any cost. In fact, the Malays did not strive for originality at all. Chris is one of the most practical and effective types of blades. In addition to Malaya, similar weapons were in use in Indonesia and the Philippines.

It was possible to chop with a welding cleaver with a curved, expanding blade, but stabbing and parrying blows was very inconvenient. Faced with these difficulties, the masters of Southeast Asia decided to “boost” straight swords, adapting them for a cutting blow. Of all types of blows, cutting is the most effective. It is with these blows from swords with a microsaw on the blade that the barrels of guns are cut off and people fall apart in half. But, not owning either advanced technologies or decent raw materials, the Malays were forced to replace the microsaw with a “macrosaw” made from smooth curves of the blade. “Waves,” of course, did not make the kris equal in effectiveness to a katana or a saber. But the lack of penetrating power was largely compensated by the severity of the damage inflicted. With a piercing blow, the blade did not go straight, but “walked” to the sides; with a cutting blow, each of the passing “waves” made its own cut. To do this, the kris was sharpened like a saw - “with a collapse.” Thus, even if the wound turned out to be very shallow, quickly rotting petals of flesh, deprived of blood supply, remained between its edges. The wounds inflicted by these weapons healed very poorly.

The Malays undoubtedly borrowed the very idea of a “snake” blade from India, where such weapons appeared in ancient times. But neither in India nor in the Middle East did “flaming” swords become widespread, nor in Europe. To “bring the idea to fruition” it was necessary to solve a number of problems.

They usually cut with sharp, strong blows. But in order to cut, you need to press the blade while simultaneously pulling it towards you. In battle, when delivering a cutting blow, the Japanese katana was pressed down with the second hand, and the saber, the center of gravity of which was shifted to the tip, by its own inertia. But the easiest way to deliver such blows is with a blade similar to a Turkish scimitar. Since the invention of the sickle, it has been known that the best shape for a cutting tool is concave. But the Malays solved the problem: combining the straight blade, which is optimal for fencing, with the reverse bend of the scimitar. To do this, leaving the blade straight, they bent the handle down. In this position, while drawing out the sword, the warrior simultaneously pressed the blade into the wound. At the same time, the “pistol” grip with a developed “apple” provided the reliable support for the palm necessary for a cutting blow. There was still the problem of the guard.

Traditionally, cutting swords are devoid or practically devoid of this detail, since when struck with the base of the blade, the guard can catch on clothing. But a weapon without a guard can only be held with the blade down when parrying. It is not comfortable. The Malays decided to keep the guard. Its functions in the design of the kris were completely taken over by the blade. Its lower part was asymmetrically expanded and completely hid the hand. The outer surface of the “waves” covering the palm was sometimes covered with corrugation that would destroy enemy weapons, and the ends were sharpened and turned into additional blades. Thanks to the additional blades, when fencing with a kris, a blow with the guard also “counted.” But to safely carry the kris, a special “T-shaped” sheath was required.

In general, the medieval kris was an attempt to obtain an acceptable result, with unsatisfactory initial capabilities. And perhaps all the advantages of Chris appeared only in modern replicas. Using modern materials.