New York tea salons as a breeding ground for fortune tellers and psychics of the 1930s (7 photos)

As the practical Uncle Fyodor used to say, in order to sell something unnecessary, you must first buy something unnecessary. And in order to check the qualifications of a fortune teller, magician or psychic and not give away your hard earned money in vain, you need to check how he will predict the upcoming events in his life. If he can predict.

Tea salons became battlegrounds in the war against fortune-telling that erupted in New York City in the 1930s between police officers and psychics.

On April 17, 1929, Miquette Cuba was fined $100 for the most unusual crime of illegal fortune-telling. She looked into the teacup of the undercover policewoman and promised her a trip on the water and a meeting with a tall brunette. But the lady made a fatal mistake, albeit only one. Taking a modest fee of 25 cents for a prediction, she fell into the trap of the city police department. Taking a fee for fortune telling was a direct violation of the law.

Beginning in the late 1920s, fortune telling tea parlors flourished in American cities from Pittsburgh to Portland. They appeared as a response to the growing popularity of the supernatural. And the most popular topic was the image of gypsies. Staff were decked out in colorful shawls, guests were entertained by violinists, and smartly and colorfully dressed fortune tellers told guests fortunes using tea leaves, palms, or crystal balls.

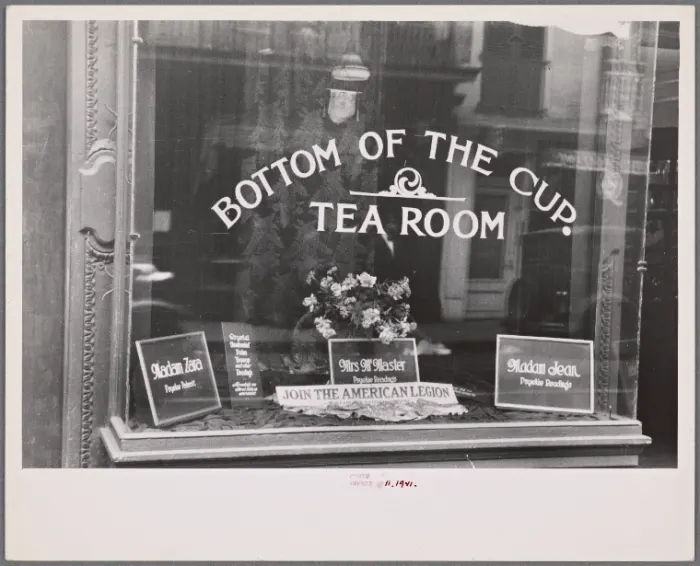

Madame Jean, Madame McMaster or Madame Zara will tell your fortune

At places like the Gypsy Tea Room, where Miquette Cuba worked, a glimpse into the future was a bonus for ordering tuna salad, sandwiches, ice cream, tea and pie.

From a legal standpoint, so-called glimpses into the future should have been free. Laws prohibiting fortune telling have been in effect for many years. But by the 1920s they were significantly tightened. Fortune tellers in New York were not allowed to charge fees. They could rely solely on tips. Anyone caught openly telling fortunes for money was fined hefty sums.

Mary Shanley was an undercover cop who hunted fortune tellers.

That's how Miquette Cuba became hooked. A couple of weeks before her capture, policewoman Mary Vaughan went undercover in a tea salon to catch a fortune teller in the act. Vaughan and her colleague Lillian Harrison headed the department's secret department to combat fortune tellers. Since the tea rooms were mostly visited by ladies, it was the female police officers who took the initiative to collect evidence against fortune tellers.

In 1931, the New York Times accused teahouse fortune tellers of causing "a wave of melancholy among women" with their murky predictions. Since many fortune tellers were of gypsy origin, a certain amount of hype in the press was also provoked by national motives.

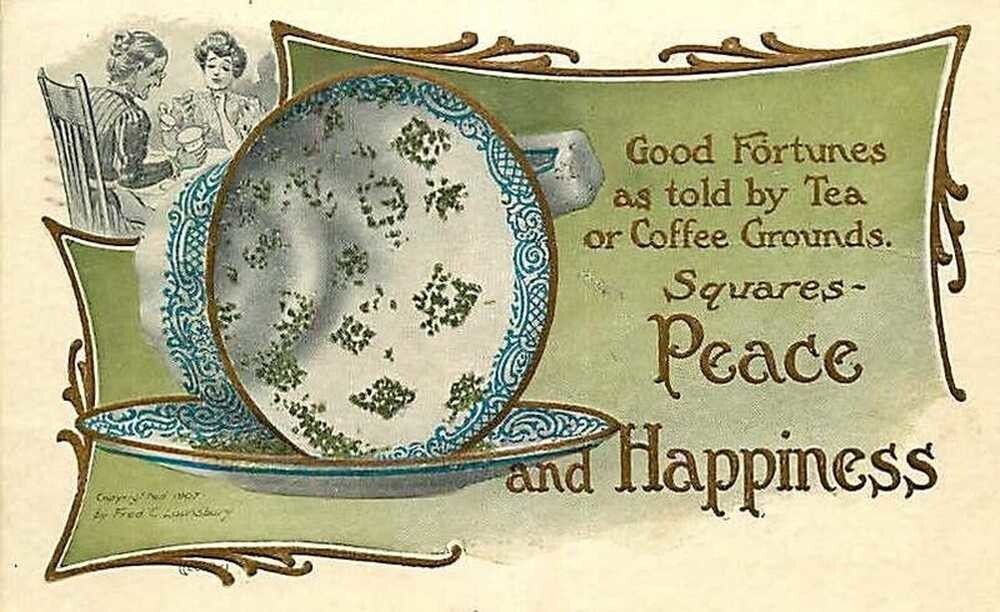

Peace and happiness are found in tea leaves

The common practice of these fortune tellers was to tell a woman nonsense that her husband was having an affair with a beautiful curly blonde. Which, of course, did not add love and harmony to the family atmosphere.

In the first half of 1931 alone, more than a hundred convictions were handed down against New York fortune tellers. The American Society of Magicians, probably worried about their reputation, also joined the whistleblower campaign led by city police chief Mary Sullivan. It presented a letter from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, saying they had no evidence that destinies could actually be predicted.

Sullivan personally went undercover. And none of the objects of her development were notified by the stars, ghosts or magic balls that their client turned out to be an undercover policewoman.

Gypsy fortune tellers of 1930s New York

Raids continued throughout the 1930s. On April 20, 1934, six policewomen and eight detectives raided three tea shops on the same street. The result was the capture of a dozen fortune tellers who had to appear before a magistrate.

Despite pressure from the police, tea salons remained a popular source of entertainment and pastime due to their accessibility. In 1935, the ballad "In the Little Gypsy Tea Room" rocketed to the top of the international charts. And this further fueled interest in the establishments. Plus, in a country gripped by the Great Depression, fortune tellers served, perhaps, as the main consultants in the matter of finding a job.

However, by the beginning of World War II, raids began to cause serious losses. On April 1, 1941, fortune teller Anna Mead pleaded guilty to fortune telling after being caught by a policewoman. At the trial, the fortune teller explained that she was aware of the inadmissibility of paid fortune telling. After completing the fortune-telling practice, the teahouse began to lose clientele and was on the verge of ruin. And she began to guess again. Against this background, the popularity of tea salons began to gradually decline.

Nowadays in New York, it is illegal to claim your ability to speak with spirits or remove curses and charge for it. Fortune telling is allowed only if clients are notified that the predictions are for entertainment purposes only.

However, the industry of fortune telling and related services continues to flourish on city streets. Only now, clients who want to look behind the veil are offered not a piece of cake with a cup of tea as an enticement, but bright, mesmerizing neon signs. To the advertising of which gullible citizens who want to part with honestly earned money in exchange for information of dubious value fly like moths to a flame.